At Law School, honor for the enslaved

Plaque dedicated in plaza honors contributions they made to founding 200 years ago

As part of Harvard University’s efforts to recognize its early ties to slavery, officials yesterday unveiled a memorial to honor the enslaved people whose work helped found Harvard Law School.

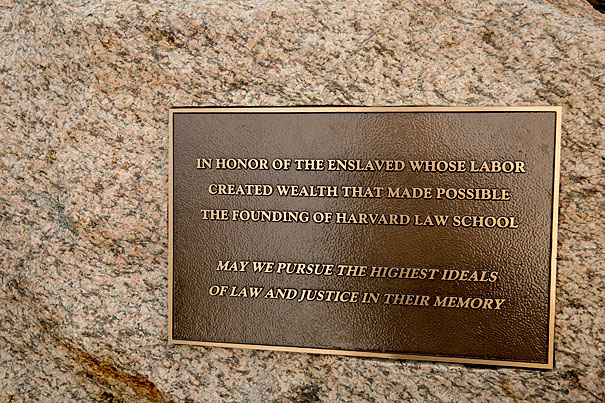

Located in the center of the Law School’s plaza, the new stone memorial features a plaque that recognizes “the enslaved whose labor created wealth that made possible the founding of the Harvard Law School,” and urges in response that the School “pursue the highest ideals of law and justice in their memory.”

The nation’s oldest professional law school was established in 1817 with a bequest from Isaac Royall Jr., a wealthy man from Medford, Mass., whose family made much of its fortune in the slave trade and on a sugar plantation in Antigua.

Last year, the Harvard Corporation approved the removal of the Law School’s shield, which had included three sheaves of wheat, derived directly from the Royall coat of arms.

Harvard President Drew Faust unveiled the new memorial with Annette Gordon-Reed, the Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History and professor of history, in an evening ceremony that drew 300 people.

“Slavery is an aspect of Harvard’s past that has very rarely been acknowledged,” said Faust, a historian of the Civil War and the American South. “The presence and the contributions of people of African descent at Harvard are stories that have been mostly left untold. We must change that reality.

“As we acknowledge here today, Harvard, along with many other institutions in New England, was directly complicit in America’s system of racial bondage from the College’s earliest days in the 17th century until the ending of slavery in Massachusetts in 1783,” Faust said. “Harvard continued to be involved indirectly through extensive financial and other ties to the slaveholding South up to the time of emancipation” in 1863.

Faust commended Law School officials for choosing the memorial ceremony to kick off the School’s bicentennial celebrations, and she lauded its commitment to exploring its past.

“How fitting that you should begin your bicentennial with this ceremony reminding us that the path toward justice is neither smooth nor straight,” said Faust. “Let us dedicate ourselves to the clear-eyed view of history that will enable us to build a more just future in honor of the stolen lives we memorialize here.”

Recognizing the legacy of slavery at the Law School is important for coming to terms with the past and for reminding future lawyers of their duty to make the legal system wiser and fairer, said John F. Manning, the School’s Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and professor of law.

“Our School was founded with wealth generated through the profoundly immoral institution of slavery,” said Manning. “We should not hide that fact nor hide from it. We can and should be proud of many things this School has contributed to the world. But to be true to our complicated history, we must also shine a light on what we are not proud of.”

Gordon-Reed, who has written extensively about slavery and who drafted the words on the plaque, said the memorial doesn’t contain names because it’s impossible to know the identities of all the Africans the Royalls enslaved in Antigua and Medford, whose work built much of the wealth used to found the Law School.

“The words are designed to invoke all of their spirits and bring them into our minds and our memories with the hope that it will spur us to try to bring to the world what was not given to them: the law’s protection and regard, and justice,” she said.

Researchers have found Royall family records naming some enslaved men, women, and children on the Medford estate, but most of them are listed without surnames, and some are nearly unknown, inventoried with descriptions such as “Old Negro Man,” “House Peter,” and “Girl, six years of age.”

In a touching moment during the ceremony, Janet Halley, the Royall Professor of Law, who has spoken openly about the connections between her chair and slavery, read aloud the names of those enslaved who were found listed in the Royalls’ records.

“These names are the tattered, ruined remains, the accidents of recording, and the encrustation of a system that sought to convert human beings into property,” Halley said. “But they’re our tattered, ruined remains.”

The memorial dedication followed a talk by Dan Coquillette, the Charles Warren Visiting Professor of American Legal History, whose research in 2000 helped unearth the ties between the School and slavery, and a panel discussion with Gordon-Reed, Halley, Randall Kennedy, the Michael R. Klein Professor of Law, and Bruce Mann, the Carl F. Schipper Jr. Professor of Law.

Coquillette co-authored the 2015 book “On the Battlefield of Merit: Harvard Law School, The First Century,” which recounts the School’s early history and traces the life of Isaac Royall Jr.’s father, Isaac Royall Sr., who moved with his family to Massachusetts a year after a 1736 bloody slave revolt on Antigua.

For law student Laura Older, the ceremony and the talk underscored Harvard’s willingness to acknowledge and address the injustices of the past.

“It’s really lovely to hear them talking about something that is really both important and difficult to talk about,” she said as she lingered near the stone memorial. “But we’re going to talk about it because it needs to be done.”