A new Harvard study finds that a majority of college freshmen believe their peers have more friends and fun.

iStock

Not a popularity contest

Most college freshmen assume classmates have more friends and fun, which may influence their efforts to make new friends, study says

As the title of her 2011 memoir, actress and writer Mindy Kaling asked the tongue-in-cheek question “Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me?,” neatly encapsulating her self-deprecating persona as an insecure social butterfly.

Though the title was intended as a joke, for many people feeling left out or worrying that classmates are out partying while they’re all alone in their dorm rooms can be all too real and far too frequent, especially when navigating an unfamiliar social scene like campus social life.

Researchers have long known that having friends plays an important role in shaping a person’s sense of well-being and belonging. Even physical health is dramatically affected by feelings of social connectedness. But little has been understood about how people’s perceptions of their own social life and the social lives of those around them affects their emotions. Another question is whether these perceptions, however accurate, affect people’s abilities to form friendships.

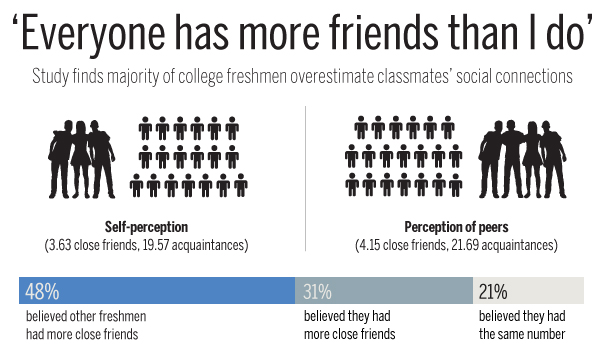

A majority of first-year college students believe their peers have more friends and are “hanging out” more than they are, according to a new paper from faculty members at Harvard Business School (HBS) and Harvard Medical School (HMS).

In a study of 1,099 freshmen in their first semester at a public university in Vancouver, Canada, 48 percent assumed that other freshmen had more close friends than they did. Only 31 percent thought they had more close friends than their peers, while just 21 percent believed they had the same number. When asked whose social circle was larger, 45 percent thought others had more friendly acquaintances than they did themselves. Estimating that others had more exciting social lives was consistent across gender and ethnicity, and was true whether a student had gone to a local high school or came from out of town.

Studying a second group of freshmen over their first two years of college, the researchers found that those who believed other students had only moderately more friends than they did later reported making more close friends and social acquaintances during the academic year, suggesting that perceiving a small-but-surmountable gap in friendships may serve to motivate students to socialize more.

Ashley Whillans, the paper’s lead author and an assistant professor at HBS, said prior research showed that people tended to overestimate how smart and capable they themselves really are, so she was somewhat surprised by the findings.

“We know from social-comparison research and social psychology that a lot of people think they’re doing better than others, so we thought maybe students think that they have a lot of friends and their peers don’t,” she said. The researchers decided to study college freshmen because of how important social life is to young people and how integral it is to a positive college experience. The transition from high school to college is often a challenging time of social upheaval.

Co-author Alexander Jordan ’03, a clinical psychologist at McLean Hospital and an instructor at HMS, said the spark for this research came to him when he was at Harvard College and noticed that students often believed others had more active social lives than they themselves did. During graduate school in 2004, he said a similar dynamic appeared to be at work, as Facebook and social media grew in popularity and some students tried to cultivate online personae that seemed happier and more socially engaged than they were in real life.

Students were less likely to think close friends had better social lives than that acquaintances did, because estimations of the former relied less on superficial observations from afar.

“Because when we’re out in public, we look out into our social environment and we see people happy and laughing, and we don’t see when people are alone, upset in their bedroom,” she said. “When you’re new to a social network, you feel uncertain, you’re not sure about your role in that social network, you’re not sure about other people’s roles, so you might be more willing or more likely to anchor your judgments of yourself and others based on what you can observe.”

Some simple interventions may help ease student discomfort, said Whillans, such as talking openly with other students about how feeling lonely or less popular than peers is common, or simply sharing how hard it can be to make new friends. Students might also document a day in their lives so others can see how they really spend their time, instead of assuming that everyone else is flitting from party to party while they’re stuck at the library.

“What I hope that people take away from this research is that the feelings that you’re not doing as well as other people when you’re new to a social environment are normal — more normal than most people would intuit … Chances are that other people are feeling that way too, and that can actually be motivating.”