Year Up gives underserved youth a step up

Harvard-partnered program helps ‘close the opportunity divide’

On the website it’s called closing the opportunity divide, equating economic justice with economic prosperity.

In real life it means helping a young person who’s seen friends and relatives die young, who’s known poverty, drugs, violence, and even homelessness, realize his professional potential.

That’s the work of Year Up, the brainchild of Harvard Business School graduate Gerald Chertavian. Since it began in Boston in 2000, Year Up — a nonprofit program that helps underserved young people gain the skills and discipline they need to succeed — has trained and placed nearly 17,500 young people in professional internships in 21 cities.

One of them was Stanley Fenelon. And for him, it was a game-changer.

Fenelon grew up rough in Brockton. “My brother, sister and I all have different dads, and it was just our mom and us kids … It was the same story as most: urban city, poverty, a lot of drugs and violence,” he said.

Gun violence quickly became an issue. By high school he was regularly attending friends’ funerals, but when his cousin was killed weeks after turning 14, it shocked him.

“He was shot three times. I was 16 at the time,” said Fenelon. “It was a pivotal moment when I had to see him lying in the casket. It inspired me to strive for a better life.”

Fenelon graduated from Brockton High School, and began classes at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. After a year he transferred to Palm Beach State College in Florida, moving in with his father for the first time. But the father-and-child reunion wasn’t happy, school didn’t work out, and soon Fenelon was homeless and jobless.

“It was tough, but sunshine is great when you’re homeless,” he said.

A man of optimism and perseverance, Fenelon eventually found a job. He worked hard, got his own place, and was even able to buy a car. But then he was injured at work and had to move back to his mother’s house in Massachusetts to recuperate.

It was while he was recovering that he learned about Year Up. And after six months of training and another six working in an internship, Fenelon was launched on a successful career. He is now 25 and a business systems analyst in the Harvard University Information Technology unit.

“I saw that our country had incredible young people. … They’re often smart, ambitious, hungry, motivated, and incredibly talented, yet they have absolutely no idea how to move that talent to productive capacity.”

— Gerald Chertavian

Fenelon is one on a long list of successes for Chertavian.

In 1987, the Lowell, Mass., native and recent Bowdoin College graduate was 21 years old and living in New York City when he signed up with the Big Brothers Big Sisters organization. He was partnered with David, a 10-year-old boy living in one of the city’s most dangerous housing projects.

Over the next three years, they spent every Saturday together, and those weekends changed Chertavian’s life.

“I saw that our country had incredible young people — people like David — living in places like that,” Chertavian said. “They’re often smart, ambitious, hungry, motivated, and incredibly talented, yet they have absolutely no idea how to move that talent to productive capacity. I saw so clearly that it was David’s ZIP code, his mother’s bank balance, the color of his skin, and the school system he attended that were limiting his God-given potential.”

Chertavian left New York in 1990 to attend Harvard Business School, which he graduated in 1992. He married, founded a company, became successful, and moved to London. He also kept in touch with David, visiting him as often as he could and ultimately bringing him to London, too. David, he said, was part of his family.

David’s success showed Chertavian what young people can do when given a chance, he said. And the question of how he could help change the trajectory of the lives of other disadvantaged kids stuck with him. It nagged at him so much that when he sold his company, there was never any doubt as to what he would do next.

In 2000, Chertavian poured much of his newly acquired wealth into founding Year Up. The organization’s mission is to support and empower urban youth.

“There are 6 million Davids in this country today,” Chertavian said. Statistics that show that one out of seven 18- to 24-year-olds is out of work, out of school, and with no more than a high school education — a “recipe for disaster” in a knowledge-based economy, Chertavian said.

One year for a new life

Thus: Year Up. The model is simple — commit to a year and learn how to change your life. But the training is rigorous.

The first six months are spent in the classroom, learning technical and professional skills. Students can choose one of five tracks: financial operations, information technology, business operations, software development, or sales and customer support. There are also life skills: how to dress and maintain professionalism in the workplace; the art of networking; the importance of punctuality, preparation, and determination.

Most of all, they’re taught discipline, and it’s that which what drives Year Up’s stringent point system. Students start with 200 points, which they can lose for infractions — even seemingly minors ones such as an untucked shirt, lateness, or missing an assignment deadline.

The points translate into money. Year Up participants are given a small stipend to help offset costs of the program. You lose points, you lose money — a real motivator.

In the second six months, each student is paired with a mentor and placed in an internship in an entry-level position. Participating companies have the option of hiring the interns without paying a placement fee, and Year Up says it performs six times better as a talent pipeline than traditional recruitment sources.

The training is not for the faint of heart, and that’s intentional. Students come to Year Up to learn to succeed. Those who can’t handle it “weed themselves out.” It’s a distinction instructors stress in lessons and even in the terminology they use: Students “earn” infractions based upon their actions, they’re not “given” them; they “fire themselves,” instead of being fired.

The result, Year Up officials say, is young professionals with solid technical training and a commitment to respect and value others; be trustworthy, honest, and accountable; embrace diversity; continue to learn; and work hard and have fun.

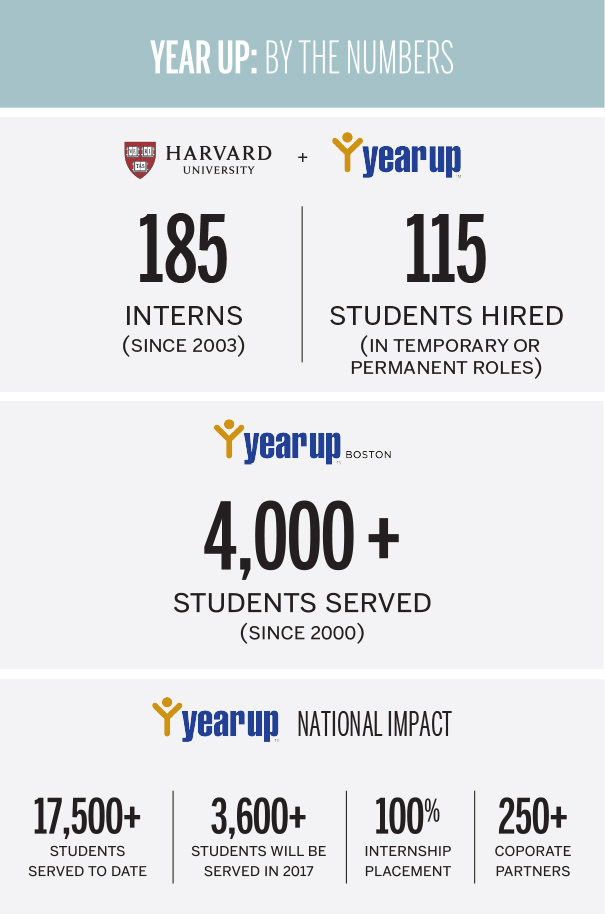

Harvard University began working with Year Up in 2003. Since then it has hosted nearly 200 interns and hired 115 of them for permanent or temporary positions. Year Up interns work in Schools and departments across the University, such as Harvard University Information Technology, Finance, Media and Technology, and athletics, among others.

Year Up officials say the partnership with Harvard is a “natural fit” because its model — sustained investment in developing and nurturing young people — aligns so perfectly with Harvard’s.

“We’re extremely proud of our partnership with Year Up, and incredibly fortunate to have so many remarkable young people placed with us as interns,” said Harvard Executive Vice President Katie Lapp. “Interns come to us already fully prepared, and that saves us time, energy — and in the long run, money. It’s a win-win for everyone. We’re helping young people start their professional lives and producing, growing, and nurturing a pipeline of talent that’s beneficial to Harvard.”

Harvard also organizes a variety of development seminars for the interns, offers mentoring, holds practice job interviews with hiring managers, helps with resume writing, and provides continuous career coaching to its individual cohorts, which have grown to more than 40 a year.

Etaine Smith, a senior human resources consultant for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), said Year Up’s interns arrive “ready, set, and equipped to contribute.”

“They have the technical skills — whether it’s accounting or financial or IT skills. But they have the life skills too, as they know how to communicate, how to introduce themselves, how to act professionally. They know how to present what they can and cannot do, and are enthusiastic to learn new skills. These are all skills that will serve them well in life, as well as here at Harvard.”

Since the beginning of the partnership, hundreds of Harvard employees have volunteered to serve as mentors not just to interns working on campus, but to those placed in companies across Greater Boston.

“I’ve thoroughly enjoyed getting to know my mentee, and have learned as much from her as I hope she has from me. It has been one of the most rewarding experiences I’ve ever had, and I highly recommend it to anyone looking to meet, and make a difference in the life of, someone who’s just beginning their career,” said Amy Nostrand, assistant vice president for finance and administration at Harvard.

A growing concern

Year Up’s timing seems perfect. An article in the Boston Globe last month headlined “Help (desperately) wanted in Massachusetts” reported: “Massachusetts finds itself at a remarkable economic moment. Holding us back is an ample supply of labor.” The article cited a recent report by MassBenchmarks, a company that tracks economic trends in Massachusetts, that found the commonwealth is “facing looming constraints on growth as a result of a shortage of available skilled workers.”

Chertavian said that in the U.S. today, there are at least 12 million jobs that will go unfilled in the next decade if we can’t find the talent and skilled labor to fill them. Year Up is prepared to step in and help fill that void.

“We provide a strong, diverse pipeline of talent to our partners,” said Anita Fulco, director of partner relations at Year Up Greater Boston. “The program makes good business sense. It’s a money-saver for organizations like Harvard because Year Up internships reduce the time and costs associated with all that typically goes into a hire — the recruiting, onboarding, and training.” In addition, she said, Year Up employees tend to stay 50 percent longer in a job than other entry-level employees.

“Many of these young people have external challenges, which many would say work against them,” Fulco said. “But they’re not your typical employees. They have tremendous grit and perseverance. They want to be there. And they’ve worked incredibly hard to come as far as they have to get there.”

The organization itself has grown, from 22 participants and two staff members its first year in Boston, to offices in 21 cities nationwide. And for the participants?

According to Year Up, 90 percent of their graduates are working and/or enrolled in post-secondary education within four months of completing the program. For employed graduates, the average starting wage is $18 an hour, or approximately $36,000 annually.

“That is livable wage money in this country,” said Chertavian. “Their average annual salary before many came to us was often less than $10,000. So in one year, you’ve put yourself in a situation to be able to make a livable wage. There are not many places in America where an 18-year-old can say that they’ve made that much of a change in a single year.”

“Year Up and Harvard saw potential in me … and believed in me”

Chris Vargas, who recently interned in Harvard’s media and technology office, said he was determined not to “just become another statistic.”

“I had friends who joined Year Up and their success stories really motivated me,” he said. “The neighborhood where I grew up wasn’t all that great and so to see someone who was able to break out of that environment was really a big factor in pushing me to apply … I knew those were the types of footsteps I wanted to follow in.”

Vargas said the support systems at both Year Up and Harvard helped him succeed: “They helped me build confidence by providing the right resources and support system.”

Hillary Tan, of Malden, Mass., an accounts payable analyst in financial administration, agreed.

“The people at Year Up and here at Harvard saw potential in me,” she said. “They believed in me. They were grateful for my help and it was obvious that they genuinely wanted me to grow.”

Jamar Nelson of Randolph, Mass., began as a finance and human resources assistant in Harvard Athletics last month, but the path was not a straight one. Nearly four years ago, when Nelson started as a Year Up intern, he set the bar high and decided to earn a college degree while spending every summer working in Harvard Web Publishing. In May, he received his diploma from Framingham State University.

Throughout his college years, Nelson stayed in contact with human resources and his managers at Harvard. “I was thinking ahead. They really drilled that in at Year Up: network, network, network — and use those connections,” he said.

Fenelon echoed the point. “They have a saying at Year Up that your net worth is your network … it’s all about the people,” he said.

Chertavian said the aim of Year Up is to level the playing field. He said many young people, particularly those of color and low incomes, face steep hurdles. Rather than assess everyone as if they’d begun at the same place, he said, we should help those with the odds against them get to the starting gate.

“If we could imagine the degree of difficulty in just getting the chance to compete, we would assess talent fundamentally differently.”

If you are interested in hiring an intern or becoming a mentor, contact Amy Nostrand at amy_nostrand@harvard.edu.