Following a spate of bad press, ride-sharing giant Uber tapped Frances X. Frei, UPS Foundation Professor of Service Management at HBS, to lead major reforms at the company.

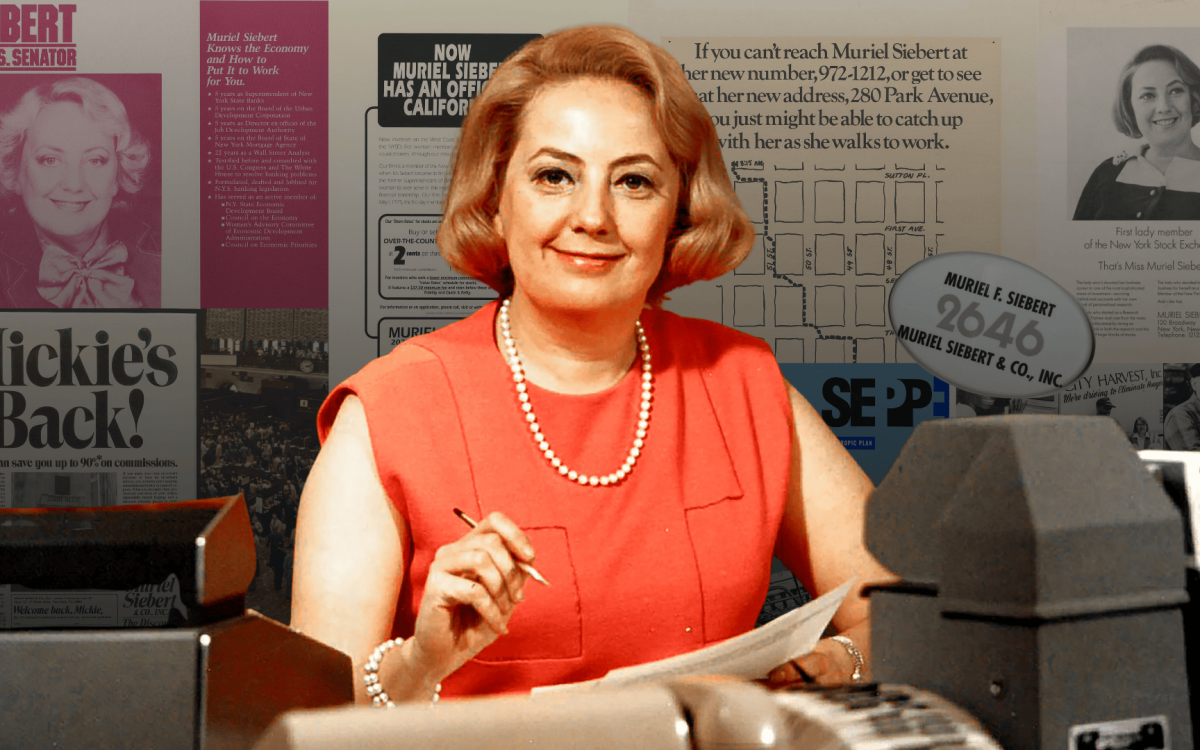

Photo by Seth Wenig/AP

Teaching Uber instead of HBS students

Frances Frei takes leave to tackle problems at rapidly growing ride-share company

After working with Harvard Business School (HBS) to adapt its campus culture and curriculum to be more inclusive of women, Frances X. Frei, UPS Foundation Professor of Service Management and senior associate dean for executive education, took a leave from the School this week to become senior vice president of leadership and strategy at Uber Technologies, the global ride-sharing company.

Frei, an authority on gender, strategy, and corporate culture, will help lead major reforms during a particularly difficult time at the San Francisco-based firm.

Uber has been battered publicly recently over its treatment of drivers, an alleged data theft from Google’s self-driving car business, an argument involving its chief executive, the abrupt departure of key executives, and accusations by a former employee of a corporate culture where sexual harassment complaints were ignored. So far, more than 20 employees have been fired, with others under scrutiny amid an internal review. The results of another review, led by former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, are expected to be released soon.

On Tuesday, her first day working at Uber, Frei spoke with the Gazette about the challenges the company faces and how she hopes to “optimize” Uber for “awesome.”

GAZETTE: Though your formal position begins today, you’ve been working with Uber behind the scenes for the last couple of months. What did the company ask you to look at initially?

FREI: Often when organizations find themselves at an inflection point, particularly service organizations, I get calls. … Someone thought I should meet Liane Hornsey, the head of H.R., and CEO Travis Kalanick. … It was a former HBS student, Meghan Joyce [M.B.A. ’12]. She wasn’t my student, but she got to witness the cultural changes that occurred at HBS. She was here year one, took a couple of years off, came back for her second year, and was like “Whoa. The culture has changed!” … I started talking to her. She worked at Uber, and when all this stuff went down, she said, “I really think you should meet with Liane and Travis.” They wanted another set of eyes looking at the concerns. I spent time and did a diagnosis of what I thought the main problems were, to see if I thought my particular skills would be helpful. And then I did a diagnostic to make sure that it’s about the good guys wanting to win, because I only help the good guys.

GAZETTE: You didn’t want to be used as a public-relations tool.

FREI: No, no. So, I spent a lot of time with the CEO and had direct conversations with him, like, “There’s this guy I read about in the press, and then there’s this person I’ve been spending a lot of time with, and help me connect the differences.” And he said, “Well, I’ll help as much as I can, but I’d also look for your help in that too.” I have found him enormously open, really wanting help, wanting to change, not exactly knowing how to change. That’s what you want in a CEO at an inflection point, one who is open to change. After doing that, it appeared to me that I could be very helpful … Travis was persistent, and then we ultimately found a way where I could take a leave from HBS and go here and do it in a way where my family could stay in Cambridge. So I’m on leave.

GAZETTE: What problems did Uber perceive it had, and what did you find once you got there?

FREI: It was a hot mess. We can pretend, but it was a hot mess. I came in and was able to come in and narrow it down to what I thought were three things.

One involved a group of leaders who were not acting like a leadership team, which meant that the CEO had to be involved in an extraordinary number of things that a CEO should not be involved in. So the CEO was acting in everything because there was not a leadership team to say, “We got this.” No. 1 is to create a world-class leadership team that is not “A plus B plus C,” but is “A times B times C.” It’s not an unusual shortcoming. It’s been fixed at many, many other organizations. It’s desperately needed here. A $70 billion company needs a really effective leadership team and a CEO with a really effective leadership team, so that they can be freed up to do the things that make the most sense for them to do.

GAZETTE: Were they micromanaging?

FREI: Not micromanaging. Honestly, they were doing what needed to be done because we didn’t have a fully functioning leadership team, so a lot of stuff was falling through the cracks. Accountability was ambiguous. So we have to create a leadership team where we’re all standing by one another’s side, we rely on one another. And that’s not a novel problem. It’s pretty well understood how to do it. So that’s one of the diagnoses. And because of the recent departures, there are several empty seats at the team table, which, on the one hand, you could be sad about, but, on the other hand, you could say, “Oh, my goodness, we should bring in a collection of individuals.” Not just the best individuals we can find, but ones who complement one another. And it is super-duper rare to have that opportunity in an organization.

Two, almost everyone who left the organization left because of a bad interaction they had with their manager. Then you think, “Well, this place must have all these terrible people managing?” Not at all. The company grew so fast that people were given management positions without having the necessary leadership training. So collectively it’s not their fault. For accountability, we have to set the managers up for success. There are about 3,000 managers. Over my time here, I’ve been designing a curriculum and started compiling it to take them through essentially a short course, all 3,000 of them in different batches around the world, to teach them to lead in an Uber context. The courses are sold out.

The participants are earnest. They’re as eager as any group of students whom I’ve taught, so I’m enormously optimistic about that. But if you have leaders who don’t act as a team, managers who have not been trained how to lead, and then a business strategy that might be well understood to some but was not well understood to all, it means that if there are discretionary decisions, the company was not rowing in the same direction. So, three, we need a clear, coherent strategy and sensible, strategic planning processes to put around it.

GAZETTE: What is a workplace culture? Who creates it, what factors affect it, and how is it manifested?

FREI: A workplace culture is created by the upper-middle of an organization. The notion that the CEO creates the culture — I think the very early companies, when everyone is trying to be like the leader and then you hire people who think like the leader, there’s a homogeneity. But the moment that folks get the memo that we’re not going to win as a homogenous team and we start bringing in diverse folks, it’s really the day-to-day managers with influence who command. So that’s the upper-middle managers, because they’re the ones holding all the meetings, they’re the ones doing all the performance evaluations. They’re the ones touching all the various aspects of it.

So if you want to influence a culture, you have to influence the hearts and minds of upper managers. The good news for a place like Uber is that the organization is desperate, desperate for a better culture. I haven’t met anyone, not one person, who wants to hold onto the existing culture. So now we simply need agreement of what it looks like going forward. Liane is far on the way to doing that, and then we have to put all the supporting processes in place. …

The CEO gets a very, very good platform, but the CEO doesn’t set the culture. The folks who are out there “doing” are the ones who set it. So if you can get them all “doing” in unison … What we want to do is to say “Look, our culture didn’t have enough unity, and if it did, maybe it’s not what we would’ve picked. So now, we’re re-architecting it.” And that’s a really healthy thing to do at a company that for the first time took a hiring pause. They did that in December, before all this stuff came out. This company went from 300 to 4,000 managers in, like, three years, across 75 countries. That’s insane. They’re not increasing the head count this year — that was planned — so that the organization can catch up and prepare itself for the next phase of hypergrowth.

GAZETTE: Can a culture be changed while retaining upper leadership, or is some housecleaning unavoidable?

FREI: A bunch of execs have left in the last three months. Maybe nine people just left. I’m coming in. I expect a couple more to come in. That’s plenty of change.

GAZETTE: How will you know if meaningful change really takes place?

FREI: Best place in the world for engineers, best place in the world for women, best place in the world for men. I want us to attract and retain the absolute best talent. I want every driver to want to drive on this platform, every rider to ride on this platform, every city to be thrilled that we’re a part of it. I think the metrics will be quite clear.

GAZETTE: So it won’t necessarily be financial success or growth, it will be consensus that this is an ideal place to work?

FREI: Yes. And growth, to me, will really follow that. I’ve never found that you have to optimize for growth. I think you optimize for being awesome, and growth follows.

GAZETTE: Why do think the tech industry, which has been at the forefront of many positive changes in corporate America, has lagged behind for so long in areas like sexual harassment, gender equity, gender and racial diversity? It seems their Achilles’ heel.

FREI: I completely agree with your assessment. I don’t have the diagnosis clearly understood, but I will tell you that the number of people in Silicon Valley who have reached out to me to say “Let’s join together and understand this diagnosis and creatively come up with an optimistic path forward for the whole industry” is overwhelming. That is our challenge in 2017. … People are very keen to learn from what we do … and are wishing us well. Because if we can fix it, they can fix it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.