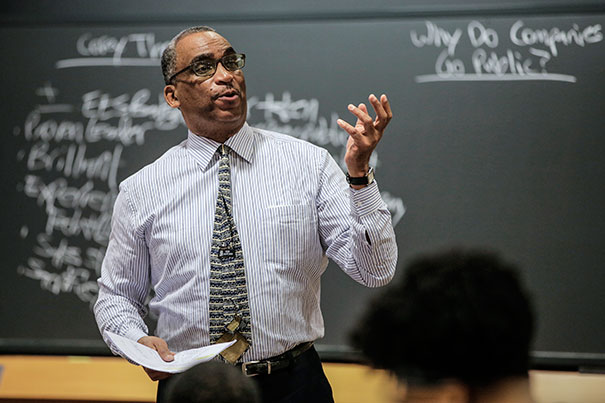

“When I was a student, we had 300 case studies our first year, and only one of those had an African-American protagonist,” said Steven Rogers, a senior lecturer whose course “Black Business Leaders and Entrepreneurship” was designed for the Business School. “The younger generation [of African-Americans] has embraced the philosophy that if you want success, you can be your own boss.”

Amelia Kunhardt/HBS

Black leadership, front and center

At Business School, students analyze case studies of minority business figures and their challenges

When Steven Rogers was a graduate student at Harvard Business School (HBS), he couldn’t help but notice how little he was learning about black leaders in the business world. Now a senior lecturer on entrepreneurial finance at HBS, Rogers is working to change that with the course he’s now teaching, “Black Business Leaders and Entrepreneurship.”

The course has already brought some big-name entrepreneurs to speak to Rogers’ students.

“It came about to address what I feel was an unintentional exclusion of black protagonists,” Rogers says. “When I was a student, we had 300 case studies our first year, and only one of those had an African-American protagonist.” Since returning to teach, Rogers has combed case studies and found blacks were represented in about 70 cases out of 10,000. “So now it’s 30 years since I was a student, and the situation is basically the same. I don’t feel it was an act of commission, more one of omission: People just didn’t think too much about it.”

Rogers says that black entrepreneurs are the “hidden figures” of the business world. “Even during slavery, you had people like James Forten, a slave whose owner allowed him to start a company making sails for ships. He created his own company and bought freedom for his family. After slavery, blacks found that entrepreneurship was an important tool, a means by which they could seek wealth. After the Civil War, the collective wealth of the black business community was today’s equivalent of $50 million.”

Currently, Rogers says, the black community is seeing a similar boom in entrepreneurship — in large part due to a change in attitude about running one’s own business. “The younger generation has embraced the philosophy that if you want success, you can be your own boss. And that’s different than 30 years ago, when it wasn’t always considered cool. Especially in the black community, there was a sense of ‘Why not just take a great job when we finally have these opportunities?’ But now you’re seeing more positive role models, on television and other media.”

Some of those role models have participated in the course. One notable guest was Valerie Daniels-Carter, whom Rogers calls the “queen bee” of franchising in the black community. The Milwaukee native, who appeared via Skype, owns 140 Burger Kings and Pizza Huts, making her one of the country’s largest franchisees. She is also part-owner of the Milwaukee Bucks basketball team. More recently, she has invested some of her earnings into building a hospital in Africa. “In that sense she’s an incredible role model, someone who got successful and then gave back to the black community,” Rogers says. “The students got to hear advice from an expert, and some of them said, ‘I had no idea people like this existed.’ ”

The class got a chance to talk strategy with Linda Johnson Rice, the publisher of Ebony magazine. When she came to Harvard in February, Rice was deciding the future of the magazine, which, like most media publications, has come on tougher times. She needed to decide whether to sell the company, close it, or seek financing to keep it afloat. She’d already made her decision, to sell Ebony to a black-owned equity firm, but kept that hidden from the students until they’d attacked the problem in class.

“Ebony makes a great case study of working an underserved market. When they started, you never saw a black person in the news unless they’d committed a crime. But now they’ve been hit by the same storm that affects all the media,” says Rogers. “So we approached the class like, ‘If you were Linda, what would you do?’ ”

Second-year student Bruce Hampton says he found that class particularly inspiring. “She talked about how she wanted to preserve the ethos of the magazine, by selling it to a minority-owned company. I worked in financial services and private equity before coming to Harvard, and it inspired me to see someone who’s walked the same path, someone I’d like to emulate. Seeing how she perseveres gives you the confidence to succeed as well.”

That kind of reaction is just what he’s aiming for, Rogers says.

“I can tell you that no other business school has ever done a course like this, and if you don’t know these stories, you’re missing a lot. Black students get to see people who look like them, who deserve to be recognized and celebrated. And nonblack students get to see some good examples of black brilliance.”