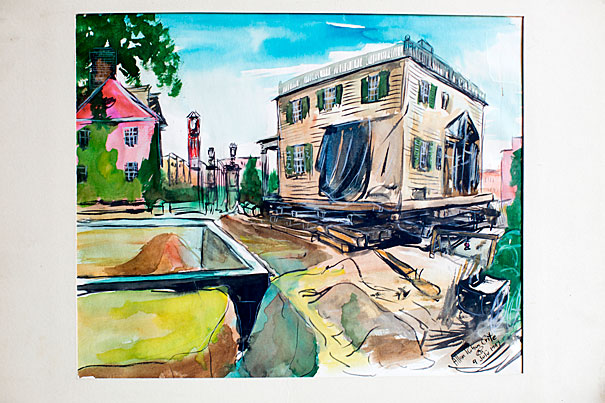

On display as part of an upcoming exhibit on slavery, this Allan Rohan Crite watercolor depicts the Dana-Palmer House, home of Harvard College and Law School graduate Richard Henry Dana Jr.. who helped found the anti-slavery Free Soil Party and later defended fugitive slaves in court.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

The focus is Harvard and slavery

Pusey Library exhibit details the University’s connections to a deep past still being uncovered

To tell the story of Harvard President Charles William Eliot, the American academic who transformed the School in the late 19th century from a regional college into the model of a modern research university, one need only consult Harvard’s archives, where rich and detailed material fully documents his lasting impact.

But to tell the story of Harvard’s long-forgotten ties to slavery, one must dig much deeper. For several years, a number of Harvard historians, faculty, students, researchers, and archivists have been doing exactly that, scouring documents both at Harvard and beyond looking for clues that help paint a picture of the enslaved men and women whose lives were intimately tied to the University’s early years and to the broader slave-based economy that helped Harvard thrive.

It’s painstaking work, as the new exhibit “Bound by History: Harvard, Slavery, and Archives,” which contains much of what researchers have uncovered so far, makes clear.

“You really do have to read through these documents almost line by line because there are just these tiny little references that are hidden,” said Harvard archivist Juliana Kuipers, who worked on the exhibit. “It’s not going to be something that jumps out.”

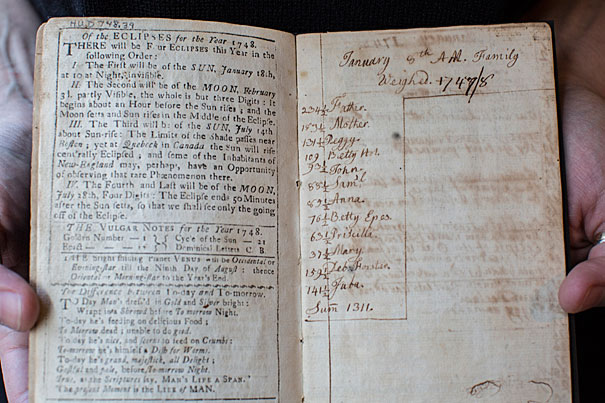

For example, a researcher could easily have missed the note in a detailed diary from 1748 kept by John Holyoke, the teenage son of Harvard President Edward Holyoke. In it, John recorded the weights of his father, his mother, his several siblings, and someone simply referred to as “Juba.” (Slaves were often denoted by a single name, one frequently taken from the Bible, said Kuipers.) To confirm Juba’s status, archivists consulted digitized records at First Church in Cambridge that indicated he married a slave owned by a Harvard professor.

The diary is part of the new exhibit opening today that was developed in tandem with Friday’s daylong symposium at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study titled “Universities and Slavery: Bound by History.”

“We thought it would be really interesting to put some of this material up on display at the very moment that the conference was going to be happening” said University archivist Megan Sniffin-Marinoff. The show includes material discovered by students from a 2007 Harvard and slavery seminar led by historian Sven Beckert, and the subsequent Harvard and Slavery research project and 36-page booklet titled “Harvard and Slavery: Seeking a Forgotten History.”

Assistance also came from The Colonial North America Project at Harvard University, an ongoing effort to digitize all known archival and manuscript materials in the Harvard Library that relate to 17th- and 18th-century North America. “As we digitized and cataloged these materials for first time, we discovered a lot of [information relating to] slaves,” said Sniffin-Marinoff.

The material in the new show ranges from letters and diaries to photos and class notes and is organized around three main themes: physical evidence of enslaved persons on campus, slavery as a topic of intellectual debate and discussion at the School, and tracing the lasting legacy of Harvard and slavery.

Image gallery

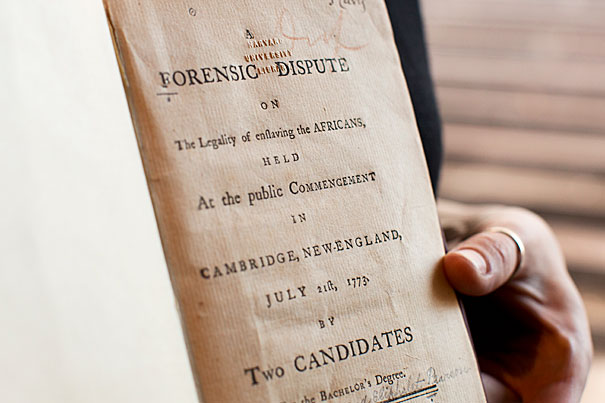

In an exhibit on slavery at Pusey Library at Harvard University is this printed copy of the Theodore Parsons and Eliphalet Pearson (both members of the Harvard College Class of 1773) debate on slavery held at Commencement in 1773. Pearson argued that the institution of slavery ran counter to the Òlaw of nature,Ó while Parson defended it. Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

In an exhibit on slavery at Pusey Library at Harvard University, this diary of John Holyoke, son of Harvard President, Edward Holyoke shows an entry from January 8, 1748 where John lists the weights of his family, including Juba, an enslaved man owned by the Holyokes. Juba weighed 141 ½ pounds. Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

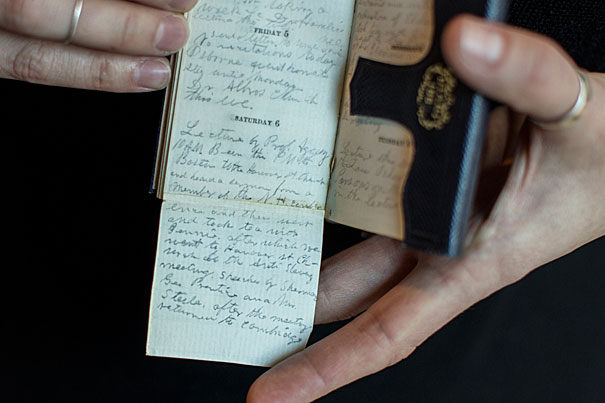

Pocket diaries kept by George Everett Marsh. On April 6, 1861, Marsh noted that he attended a lecture by Professor Louis Agassiz (who taught polygenism, an idea that was at the heart of the scientific racism that some used to defend the institution of slavery) in the morning, then in the afternoon, Marsh ventured into Boston to an anti-slavery meeting. These notes are part of an upcoming slavery exhibit at Pusey Library. Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

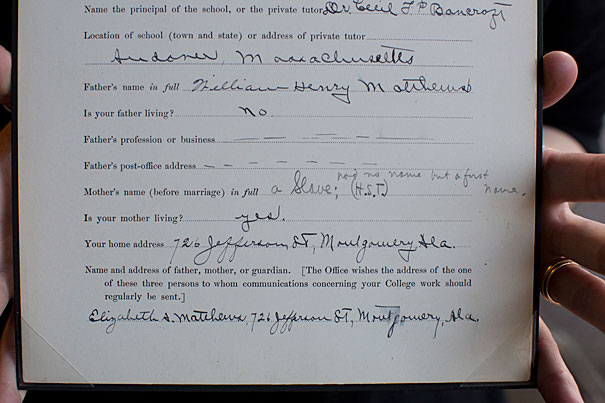

In an exhibit on slavery at Pusey Library at Harvard University is this biographical form, completed at enrollment in 1901, for William Clarence Matthews, member of the Harvard College Class of 1905. Assistant Recorder Henry Smith Thompson annotated and initialed the form with the explanation that Matthews’ mother, Elizabeth, was a former slave who had no last name before her marriage. Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

On display near the Holyoke diary is a bill sent from the shoemaker William Manning to Sarah Bordman, the widow of Harvard steward Andrew Bordman, on Aug. 23, 1771. The invoice details the monthly repairs to the shoes of “her negro Cato.”

Other exhibit ephemera point to how Harvard faculty and students took up discussions and debates about the institution of slavery as far back as the 18th century. Some of that evidence comes in the form of a printed copy of a Commencement debate from 1773 between Theodore Parsons and Eliphalet Pearson, both members of the graduating class. Pearson argued that the institution ran counter to the “law of nature,” while Parsons defended it. Another item illustrates how the racist stereotype promoted by Swiss-born naturalist and noted Harvard Professor Louis Agassiz, who believed each race had a different origin, made its way into the School’s classrooms.

In lecture notes taken during a geology course given by Agassiz on April 26, 1860, George Everett Marsh, Class of 1862, noted the professor was teaching his theory of differing racial origins, called polygenism, which was a concept often used to defend the idea of slavery.

“Even in this geology course, Agassiz is teaching these ideas, and students are taking them in,” said archivist Ross Mulcare, who helped prepare the show. Interestingly, entries in Marsh’s pocket diary dated April 6, 1861, indicate the Harvard student attended a class taught by Agassiz in the morning, and an anti-slavery meeting in Boston later that day.

The show also explores slavery’s lasting legacy at Harvard, and some of the countering attitudes opposing the institution. There are images of several campus buildings, such as the Dana-Palmer House built in 1822. Harvard College and Law School graduate Richard Henry Dana Jr. spent some of his early years in the yellow clapboard home, once located where Lamont Library now stands, and currently nestled up against the Harvard Faculty Club. In 1848 Dana helped found the anti-slavery Free Soil Party and served as a lawyer for fugitive slaves through the 1850s.

Harvard President Drew Faust, a historian of the Civil War and lifelong Civil Rights activist, previewed the show and suggested including an image of Greenleaf, the Brattle Street home of the Radcliffe dean, where Faust lived for several years as the head of the institute in the early 2000s. James Greenleaf, who made his fortune in the slave-based cotton trade, built the house in 1859.

The Greenleaf home, Faust said in an interview, is a “piece of Harvard’s heritage and an example of how slavery, which was illegal in New England, in Massachusetts after 1783, nevertheless was very much a presence in the economy in Massachusetts and New England.”

Ensuring viewers remember those lasting ties is paramount, said its curators. “There are so many iconic buildings and important spaces on campus, most of which have connections to the stories we are trying to tell here,” said Mulcare.

Exhibit organizers said the new show is just the beginning of an ongoing effort to explore the difficult dimensions of Harvard’s past.

“The story really isn’t fully understood yet,” said Sniffin-Marinoff. “What we are trying to do is put on display examples of the kinds of evidence that you can find when you start doing this research that begin to help build this story.”

Sniffin-Marinoff envisions another exhibition in the near future, one that builds on research by faculty and others in the coming years “who are looking at this much more.”

“Bound by History: Harvard, Slavery, and Archives” is on view at Pusey Library through early April.

A recently unveiled Harvard website will focus on ongoing efforts to understand the history and legacy of slavery at the University.