Harvard students leave cars on the paved road to hike into the Clark family homestead in Navajo, N.M.

Photos by Will Li ’19

In the Navajo Nation

Service trip exposes students to another American way of life

It’s the middle of winter break at midnight on New Year’s Eve, and eight Harvard students are hiking to a cabin through snow and sagebrush in Navajo, N.M., singing Kanye West songs to distract themselves from the unsettling dark.

And so the second year of the Phillips Brooks House Association’s alternative winter break public service trip began.

The students traveled to the Navajo Nation reservation to live and work together for a week, forgoing electricity, the internet, and running water as participants in a public service and cultural exchange trip. Navajo undergraduate Damon Clark ’17 also made the trip, one of PBHA’s many immersive opportunities, last year.

“I think this experience not only builds a foundational knowledge of Native Americans and Navajo culture, but also lets Harvard students engage with a community that they’ve never worked with before,” said Clark, a social studies concentrator. “I think getting to know each other’s lifestyles is what’s important when we’re struggling with issues of diversity and history. Harvard has a commitment to Native American students, and these experiences with the larger Harvard community are needed. That’s why I took it on — that’s why I do it.”

Damon Clark ’17 (left) waits for his peers. Clark’s mother, Gwen, sifts through shelled yellow corn, which is grown and dried on the homestead.

Photos by Will Li ’19

Clark shares his devotion to diversity and community-building with the PBHA. A student-run organization that strives for social justice through social service and social action, PBHA endeavors to support community needs and promote social awareness. Officially organized in 1904, today it has 1,500 student volunteers running more than 80 social service programs in tandem with local partners, in areas ranging from health to advocacy to mentoring.

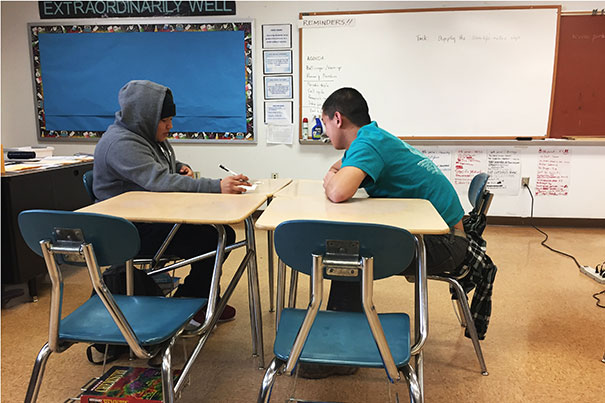

After driving from Albuquerque to Navajo, participants in this year’s trip settled in on the Clark family homestead. It consists mainly of a large shed, a one-room cabin, and a “hogan,” or traditional Navajo house, heated by wood stoves. The students stayed in the hogan, which is regularly used for a variety of ceremonies. Throughout the week, they chopped wood for heat for the nearby families, spent a day at a local high school, hiked Canyon de Chelly, shelled corn with Clark’s parents, and visited the tribal government and Navajo Nation Museum.

“I liked going to sleep early and getting up before 6, and chopping wood,” Andrew Yang ’20 said of his experience, “I liked how good of a workout it was, and how we could help keep someone’s house warm in the process. There isn’t always a lot of time during the semester to volunteer, but the breaks are a perfect time to do it.”

Service was also a draw for Will Li ’19, who is a volunteer for Mission Hill, one of PBHA’s after-school programs: “Public service has given me a sense of purpose in finding small, concrete things I can do to hopefully better the people and communities around me.” Looking back, Li said, “The coolest thing was just getting to live in an authentic Navajo way for a week, doing manual labor, hiking into the homestead, sleeping in a hogan. It gave me a more personal perspective on the culture itself, which is something I don’t think many people get to experience.”

While the Navajo Nation program is PBHA’s only Wintersession trip, there are many more run by students through the PBHA Alternative Spring Break program. This spring, students will travel to Mississippi to delve into Civil Rights Movement history, to Louisiana to explore food security and sustainability issues, and to other locations around the country. Programs give students an opportunity to partner with local organizations as they “learn about the social, economic, and political issues affecting the community, all while forging bonds with the people there and with fellow teammates,” the website says.

For Clark, this endeavor is as much about personal growth as it is about respectful cultural exchange and service to the community. “It challenges students to think in a different way. Rather than citing a source, they’re working with it, they’re listening to another person, they’re listening to themselves, they’re without an answer, and they have to figure it out. Putting students outside their comfort zone to truly learn adds to the transformative experience that Harvard aims for.”

Victor Yang ’20 (left) sets up to split some logs on the Clark homestead. Saim la Raza ’18 (right) prepares traditional Navajo frybread under the guidance of Mrs. Clark.

Photos by Will Li ’19

Without phones or the internet to fall back on, the shared week left the group feeling good about how they served as well as the connections they made together. “There was a moment at Damon’s grandparents’ house, and we were all just chopping wood,” Li recalled, “and it was like we were all part of a fluid machine — people were chopping, moving, stacking wood — and it felt like we were all connected to each other, because everyone was working so harmoniously.”

Whether it was through working together, discussing Navajo history with the Clarks, or simply reflecting on the day over dinner, students found that the trip challenged them to engage in public service, expand their knowledge of native culture, and, in a broader sense, learn how to connect better as human beings.

“We can get so caught up in what we’re doing at Harvard. We need these kind of breaks,” Clark said simply. That, and the mutual exchange between cultures, he said, are central goals of the trip he hopes will continue in its future iterations.

“You bring Harvard to Navajo, but you also bring Navajo to Harvard.”

If you are a student and would like to be a part of planning next year’s PBHA trip to Navajo Nation, please email asb_newmexico@pbha.org.