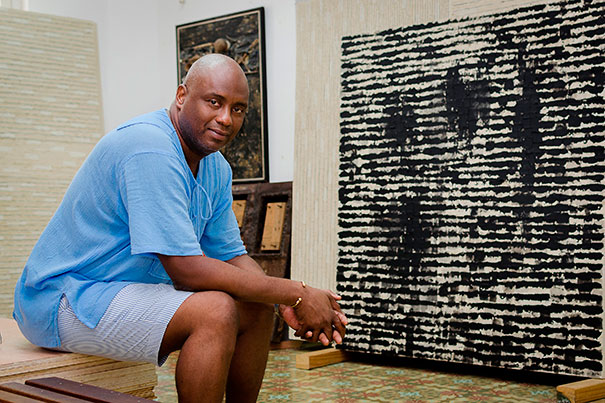

“Diago: The Pasts of This Afro-Cuban Present,” an exhibit by Cuban mixed-media artist Juan Roberto Diago, opens Feb. 2 at the Cooper Gallery.

Photo by Alain Gutiérrez

Shadows of Cuba’s past

Exhibit of works by mixed-media artist Juan Roberto Diago melds history with imagery

Slavery is in Cuba’s past, but, as in the United States, its legacy continues.

That is the ongoing career theme of mixed-media artist Juan Roberto Diago, who will exhibit 25 pieces in “Diago: The Pasts of This Afro-Cuban Present,” a career retrospective at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art.

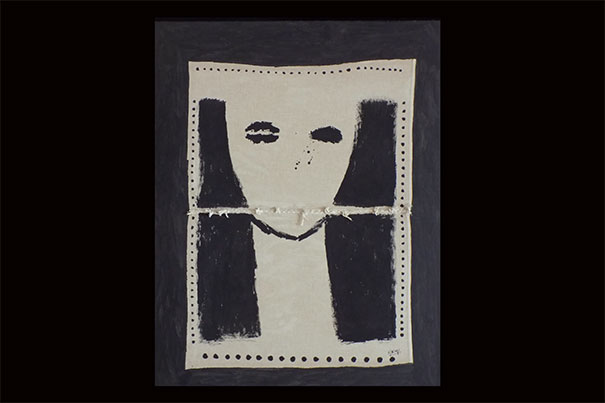

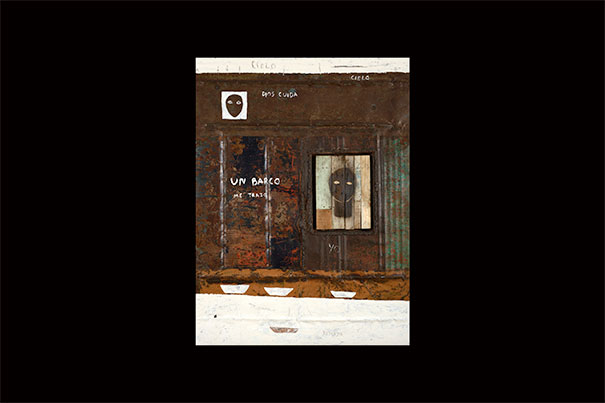

“There was a cultural legacy imposed on this country and a lot of bad thinking has been carried over,” said the artist, speaking by phone from Havana, through translator Gabriela Herrara. Using his pieces — which are of paint and found objects, often including construction material — he “tries to talk about the legacy of slavery and how it continues, going into our days.”

This legacy, as well as the history of Diago’s creative process, inspirations, and choice of materials, will be open for discussion on Feb. 3 at noon, when Diago and exhibit curator Alejandro de la Fuente host a public conversation at the gallery.

“I want to use this conversation as an opportunity for the audience to talk to him directly,” said Fuente, “about his work, about growing up in Cuba.”

Looking back, Diago describes how the history of Cuba itself contributed to his art. When the artist, who was born in 1971, finished his studies at the San Alejandro Academy of Fine Arts, in Havana, Cuba was entering the so-called “special period,” when the Soviet Union was collapsing, and Cuba was thrown into an economic crisis. Artists, at that point, “didn’t have any longer the material provided by the school. I didn’t have any other options than to go out into the street and look for what I could use.”

Image gallery

Images courtesy Juan Roberto Diago

“Whatever he could find, he would use,” the translator added.

The result is a powerful, sometimes rough-hewn body of work that mixes chunks of wood and plastic with swathes of paint and photos in pieces that may be reminiscent of Robert Rauschenberg or Frank Stella, whom Diago has met and who inspired him. Like Jean-Michel Basquiat, whom Diago also names as an influence, Diago’s art is largely focused on race and equality, issues that have tended to be downplayed in his island nation’s official history.

“The government has started fighting … inequality among their people,” said Diago. “They started implementing policy. But politics is politics, and in the everyday life it’s been very difficult to combat the mistakes of the past.”

Fuente, who has written extensively about the Queloides arts movement, which seeks to highlight the persistence of racist stereotypes and racism in Cuban society, elaborated.

“Cuba is a fairly polarizing kind of place when it comes to race and racism,” he said. “For some, Cuba has been a racial paradise, where racism was eliminated. To others, Cuba always was some kind of Communist hell, which was deeply racist “

Racial inequality, added Diago (who has participated in Queloides exhibits), has been aggravated by a burgeoning tourism industry, which has channeled limited resources to tourists and the areas they frequent. “It’s not been easy,” he said.

However, the recent thawing of relations between Cuba and the United States does have an upside. As the two countries have moved toward remaking their relationship, Cuban art has come more into focus in this country.

“There’s something of a fascination in the U.S. with Cuban art,” agreed curator Fuente. “This is due in part because for years it was hard to access Cuban art, and in part because Cuba has a very vibrant and internationally known art scene.”

The benefits of this new relationship go both ways. American artists, said Diago, can learn from Cuban artists, noting that his countrymen “have been able to produce even though they’ve had great adversity.” He, like his fellow artists, has “been enriched by his exchange with other artists, by going to other places, and having new experiences.”

Becoming a father, he noted, has added a new dimension to his work. He is now, he said, “not the same person as when I finished art school,” adding, “you can learn something new every day.”

The personal as well as the political plays into the timing of this retrospective. “Enough time has passed for artists of his time — the Afro-Cuban movement of the 1990s — for artists like Diago to have matured and to have created a body of work that we can assess across time,” said Fuente.

“I hope that in an exhibit like this people get to see Cuba beyond the caricatures,” added the curator, “beyond the headlines, that the Cuba story is part of a larger story.”

“In Conversation: Roberto Diago with Curator Alejandro de la Fuente” will take place Feb. 3 at noon at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art, Hutchins Center, 102 Mount Auburn St. The session is free and open to the public.

The exhibit “Diago: The Pasts of This Afro-Cuban Present” will be on display from Feb. 2 to May 5 at the Cooper Gallery, Tuesdays to Saturdays, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. An exhibition reception will be held 6 p.m. Feb. 1.