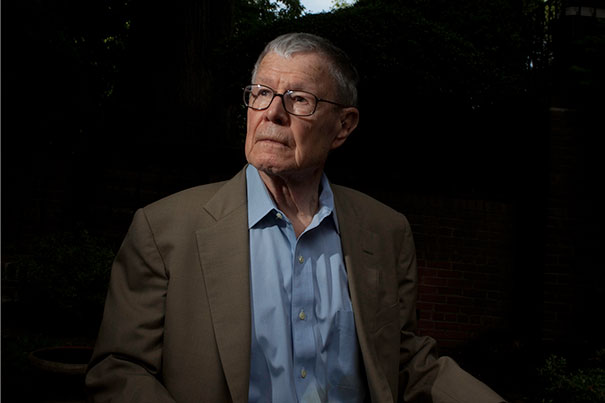

Nobel laureate Thomas C. Schelling, who was a major figure in shaping the modern Harvard Kennedy School, died at the age of 95.

Photo by Mark Ostow

Thomas Schelling, Nobelist and game theory pioneer, 95

Was co-founder of Harvard Kennedy School, Weatherhead Center

Thomas C. Schelling, whose pioneering work in game theory and understanding the “subtle tension … between conflict and cooperation” helped steady the Cold War’s nervous nuclear standoff, died Dec. 13.

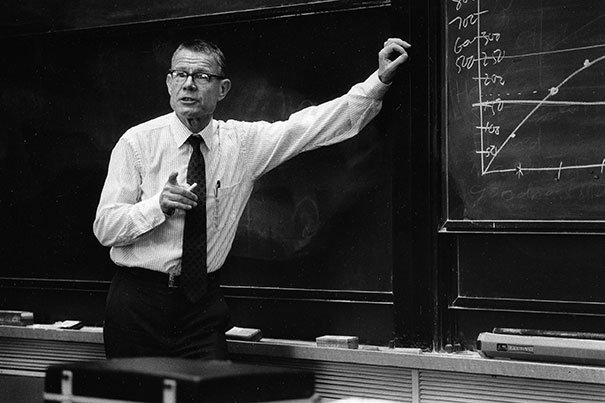

Schelling, a 2005 Nobel Prize winner in economics, provided a new way of looking at issues as disparate as nuclear strategy, climate change, and addictive behavior. At the height of his influence on public policy in the 1960s, he advised President John Kennedy during the Berlin Crisis, came up with the idea of a hotline between Washington and Moscow, and even provided the intellectual seed for the black comedy “Dr. Strangelove.”

Schelling was 95.

Among his many achievements, Schelling was a major figure in shaping the modern Harvard Kennedy School. In 1969, he was one of the School’s so-called “founding fathers,” helping design a new curriculum not for public administrators, but for a new generation of leaders literate in public policy. Schelling described the group of leading thinkers from around the School as “distinguished misfits.” The School’s core was a mix of political scientists, statisticians, economists, and decision theorists that included himself, Richard Neustadt, Philip Heymann, Howard Raiffa, Fred Mosteller, and Francis Bator.

Before his Kennedy School years, Schelling also co-founded the Center for International Affairs in 1958, which was renamed the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs in 1998. The other founders were Robert Bowie, Henry Kissinger, and Edward Mason. The center was founded at the height of the Cold War, with much attention given to warfare theory and arms control research. There was little recognition of the field of international relations at the time.

“Tom was the most lucid, most incisive, most insightful mind among the stellar band of founding fathers of Harvard’s Kennedy School,” said former Kennedy School dean Graham Allison, the Douglas Dillon Professor of Government and director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the School. “As he said, had he or Howard or Fred Mosteller or Dick Neustadt fit entirely into a department of economics or statistics or political science, they would have stayed there. Instead, while having one foot planted squarely in their disciplines, they simultaneously wanted to venture forth with the other to a new frontier.”

Schelling was always proud of the growth of the Kennedy School as well as of the proliferation of similar schools around the country. “I don’t think anybody ever anticipated such growth,” he said.

“Tom Schelling and a handful of other brilliant and dedicated scholars developed a new approach to teaching public leaders how to make better public policy, and they put that approach into action,” said Douglas Elmendorf, dean of the Kennedy School and Don K. Price Professor of Public Policy. “Without Tom Schelling, the Kennedy School as we know it today would not exist, and the world would be poorer for that.”

Schelling was born in Oakland, Calif., in 1921. He fell into economics, he said, because the economics papers he read shared his way of looking at social problems as puzzles. He went to Harvard for his Ph.D. in 1946, leaving after his course work ended to work on the Marshall Plan and then at the Truman White House. (He wrote most of his dissertation at night, working alone, after he had finished his “day job.”) He joined the Harvard faculty in 1958, while also working at the RAND Corp., where strategic thinking was a priority.

While working on the problems of a surprise nuclear attack, Schelling recalled, “I was doing it substantially as an intellectual puzzle. But as I worked through it, I realized it was a genuine, live problem.”

Perhaps Schelling’s most influential work was the 1960 book “The Strategy of Conflict.” The book focused, broadly speaking, on how parties that are ostensibly opposed can find ways to cooperate, said Richard Zeckhauser, the Frank P. Ramsey Professor of Political Economy, one of the many influential economists who saw Schelling as a mentor.

“Tom made the observation, now widely accepted but then not fully recognized, that war is far from a zero-sum game,” said Zeckhauser, who studied under Schelling as an undergraduate and later worked alongside him. “His big insight was that the United States and the U.S.S.R. had an immense joint interest in avoiding a nuclear war.”

In true Schelling style, the complex problems of superpower nuclear strategy were boiled down to the simplicity of a Wild West duel: “If both were assured of living long enough to shoot back with unimpaired aim, there would be no advantage in jumping the gun and little reason to fear that the other would try it.”

His theory’s importance in Washington in the 1960s could not be overstated. Former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara wrote, “[Schelling’s] view permeated civilian leadership under Kennedy … to a remarkable degree.”

Beyond his advice to Kennedy during the height of Cold War tensions and his efforts to diffuse them, such as the creation of what became known in popular culture as the “red telephone” connecting the Kremlin to the White House, Schelling’s influence made him a target for criticism. Some saw his fingerprints on national security policies such as the bombing campaigns in Vietnam and President Richard Nixon’s use of the “madman theory.” His power waned after he publicly opposed the 1970 invasion of Cambodia.

Later, Schelling turned his attention to a wide range of policy issues, including racial segregation, traffic congestion, and climate change. His work on rationality and how individuals could control their own behavior led him to work on substance abuse and addiction.

Schelling is survived by his wife, Alice, and by four sons.