A new study links higher amounts of greenness to lower levels of mortality. “We were even more surprised to find evidence that a large proportion of the benefit from high levels of vegetation seems to be connected with improved mental health,” said Harvard researcher Peter James.

Satellite image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture

Greenery plays key role in keeping women healthy, happy

More exposure to vegetation linked with lower mortality rates in women

Women in the United States who live in homes surrounded by more vegetation appear to have significantly lower mortality rates than those who live in areas with less vegetation, according to a new study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). The study found that women who lived in the greenest surroundings had a 12 percent lower overall mortality rate than those living in homes in the least green areas.

The study suggests several mechanisms that might be at play in the link between greenness and mortality. Improved mental health, measured through lower levels of depression, was estimated to explain nearly 30 percent of the benefit from living around greater vegetation. Increased opportunities for social engagement, higher physical activity, and lower exposure to air pollution may also play an important role, the authors said.

The study was published online today in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives.

“We were surprised to observe such strong associations between increased exposure to greenness and lower mortality rates,” said Peter James, research associate in the Harvard Chan School Department of Epidemiology. “We were even more surprised to find evidence that a large proportion of the benefit from high levels of vegetation seems to be connected with improved mental health.”

Previous studies have suggested that exposure to vegetation was related to lower mortality rates, but those studies were limited in scope, and some had contradictory findings. The new study is the first to take a nationwide look at the link between greenness and mortality over a period of several years.

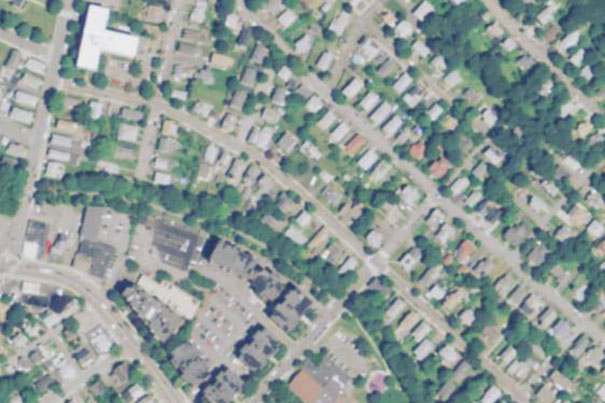

The study incorporated data on 108,630 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study across the U.S. in 2000-2008. The researchers compared the participants’ risk of mortality with the level of vegetation surrounding their homes, which was calculated using satellite imagery from different seasons and from different years. The researchers accounted for other mortality risk factors, such as age, socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, and smoking.

Varying levels of residential greenness.

Satellite images courtesy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture

When the researchers looked at specific causes of death among the study participants, they found that associations between higher amounts of greenness and lower mortality were strongest for respiratory disease and cancer mortality. Women living in areas with the most vegetation had a 34 percent lower rate of respiratory disease-related mortality and a 13 percent lower rate of cancer mortality compared with those with the least vegetation around their homes. These more specific findings were consistent with some of the proposed benefits of greener areas, including that they may buffer air and noise pollution and provide opportunities for physical activity.

“We know that planting vegetation can help the environment by reducing wastewater loads, sequestering carbon, and mitigating the effects of climate change. Our new findings suggest a potential co-benefit — improving health — that presents planners, landscape architects, and policy makers with an actionable tool to grow healthier places,” said James.

Other Harvard Chan School authors included Jaime Hart, assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Health; Rachel Banay, doctoral candidate in the Department of Environmental Health; and Francine Laden, professor of environmental epidemiology and senior author. Hart and Laden are also members of the Channing Division of Network Medicine at BWH.

Funding for the study came from the Harvard NHLBI Cardiovascular Epidemiology Training and the National Institutes of Health.