“For children of immigrants in France, hip-hop became a sort of land for those of us who felt landless,” said France-born Chilean rapper Ana Tijoux, who came to Harvard to talk about the genre’s relevance as a tool of expression for marginalized groups.

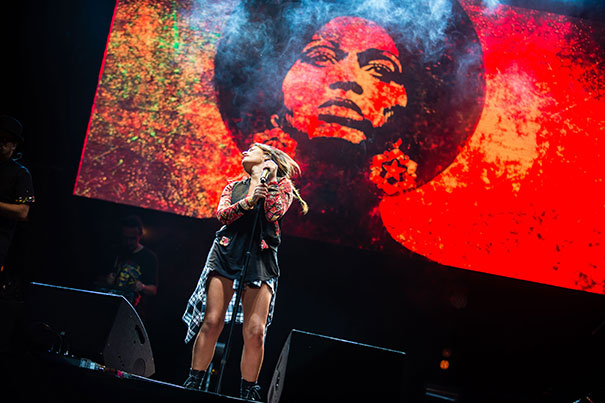

Photo courtesy of Jaime Valenzuela-Chile

For Ana Tijoux, hip-hop is home

France-born Chilean found her place in her music

Growing up, Ana Tijoux didn’t know where to call home. As the France-born-and-bred daughter of Chilean parents living in political exile, she felt conflicted about her identity — until she found hip-hop.

Tijoux first heard the music in the inner neighborhoods of Paris while accompanying her mother on her social-work rounds to immigrant families from Senegal, Morocco, Algeria, and other parts of Africa. Tijoux would play with the children while her mother worked.

“For children of immigrants in France, hip-hop became a sort of land for those of us who felt landless,” Tijoux said during an interview at a pizza parlor near Harvard Square. “We felt displaced, but hip-hop made us feel restored.”

To talk about the genre’s relevance as a tool of expression for marginalized groups, the French-Chilean rapper came to Harvard for a presentation Tuesday evening called “Ana Tijoux: Shock! Music for International Social Justice,” for which all tickets were distributed in a few hours.

Tijoux, 38, has made a name for herself as an emcee who raps about female objectification, anti-colonialism, feminism, and other social issues to tracks charged by panpipe flutes, charangos, and other Latin American folk instruments. The New York Times has called her “South America’s answer to Lauryn Hill,” and music critic Jon Pareles described her beat and flow as “calmly assertive, never strident.”

With her unique style, Tijoux’s music has crossed Chile’s borders. Her song “1977” was featured in “Breaking Bad,” while her political views earned her an interview on the television show “Democracy Now!”

Tijoux said her life informs her art and she learned her support for underdogs from her mother and her beloved Chile. In “Somos Sur” (“We Are the South”), she raps with Palestinian rapper Shadia Mansour about the value of resistance. In “Shock,” she criticizes neoliberalism and governmental corruption. In “Antipatriarca,” she sings with feminist ardor, “I won’t be the one who obeys, because my body belongs to me / I don’t walk behind you, I walk alongside here.”

Before her talk at Harvard, Tijoux, whose real name is Ana Maria Merino, recalled her beginnings as a rapper in Chile in the late 1990s with the group Makiza. With her hair in braids, a baseball cap backwards on her head, and a bright Mexican blanket on her back, she answered questions with rapid-fire speech, Chilean slang, and lots of smiles.

Her family returned to Chile after the end of the military dictatorship that ruled the country for nearly 30 years. She struggled trying to adapt during her first years in her new home, and hip-hop rescued her. “Hip-hop gave me an identity to express my frustration and anger,” she said. “It was a catharsis and it was cheaper than therapy.”

But success came too fast, she said. She broke with her group and returned to France, where she worked for three years as a nanny, secretary, and janitor, all to avoid singing. When she went back to Chile, it was for good.

Today, after several Grammy nominations, tours across the United States and Canada, and concerts in Latin America and Europe, Tijoux is at peace with fame. “My grandmother keeps all the articles and stories about me,” she said. “She likes that I’m getting recognized, and it’s fine with me.”

Her two children, Luciano, 11, and Emilia, 3, keep her grounded, she said. She enjoys watching videos on the Internet with them — she doesn’t have a television at home — and preparing avocado with marraqueta (soft Chilean rolls) for breakfast.

Tijoux said she relishes listening to Violeta Parra, a Chilean folklorist, activist, and one of her biggest musical influences. Hip-hop singers who talk about social injustice and criticize the woes of capitalism are following in Parra’s steps, she said.

“Hip-hop was a reaction to the status quo,” she said. “It was a counter-proposal, a movement of anger against the concrete, an answer to the empire.”

But hip-hop can also talk about love, motherhood, and women’s empowerment, said Tijoux.

“Music has to be honest,” she said. “I have to talk about what I see and what I feel to be true to myself.”

“Ana Tijoux: Shock! Music for International Social Justice” was sponsored by the Office of the Assistant to the President for Institutional Diversity and Equity, the Committee on Degrees in Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality, the Harvard College Women’s Center, the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, the Hiphop Archive & Research Institute, Fuerza Latina, and Queer Students and Allies.

Ana Tijoux – Vengo

Ana Tijoux ‘Vengo’