Seeing more

‘Art of Looking’ sharpens students’ critical eye

Lily Lu starts with the monkey’s face.

Sitting in the Materials Lab in the Harvard Art Museums, the freshman holds the pink rubber block firmly in place while pressing a skew chisel along the primate’s pre-printed image. The tool glides into the soft material with ease, and Lu moves quickly to the body.

“I didn’t expect a lot of hands-on stuff in the class,” said Lu. “I thought I’d only be reading and writing. Being able to interact with the materials brings an extra understanding to these pieces of art and how they came to be.”

That duality — putting art literally into the hands of students while also putting it into historical and experiential context — is at the heart of “The Art of Looking,” and has helped make the class the most popular of the three Framework Courses developed as part of the Humanities Project at Harvard. The courses — “The Art of Listening” and “The Art of Reading” are the others — are in their fourth year.

“Looking” drew 215 applications for 105 spots this spring, prompting Framework co-creator Robin Kelsey, Shirley Carter Burden Professor of Photography and chair of the Department of History of Art and Architecture, to reflect on its early success.

“This course gives students a chance to think differently about the visual technologies that permeate their lives,” he said. “It brings humanistic thinking to where the students already are, and through a series of experiential encounters, takes them somewhere new.”

He added, “There’s a tendency in our culture to think that looking is a natural act that requires no training. But looking is structured by technologies, habits, and expectations.”

A different perspective

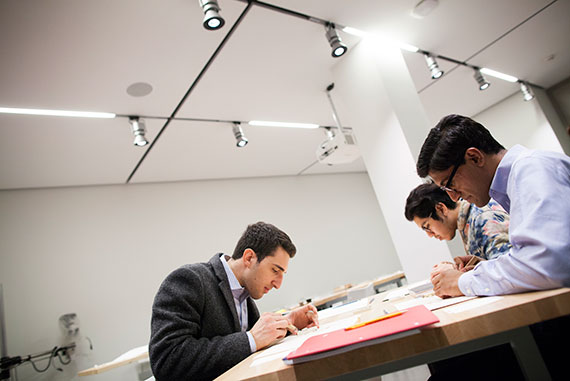

Andreas Vandris ’18 (from left), Michael Perez ’17, and Rohan Pavuluri ’18 make their own woodcuts. Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Adam Jiang ’17 compares his woodblock to his woodblock print.

Cynthia Gu ’19 examines the collection of prints.

Adam Jiang ’17 (from left), Eileen Feng ’17, museum installer and art handler Elizabeth Sirrine, and Audria Amirian ’18 study a woodblock from the collections.

Audria Amirian ’18, a concentrator in economics and government, brought a critical eye to the prints.

Kelsey’s plan for his weekly 90-minute lectures is to bring historical awareness and contextual experience to 13 technologies that have transformed visual communication. He wants students to ask big questions such as: “Why the oil painting — which culture decided it was a good form?” and “How did maps change the way the world was seen?”

The group led by head teaching fellow Matt Gin to the Art Museums on a recent Wednesday was largely made up of science concentrators intent on deepening their understanding of how to look with a critical eye. The session in the Materials Lab built on a recent Kelsey lecture on woodcuts.

Audria Amirian, a concentrator in economics and government, used a V-shaped chisel on her monkey shape, finding the work “pretty therapeutic.”

“In what way?” Gin asked.

“I guess the texture,” she answered. “I’m not sure. You don’t even have to try much. It’s the same effect of coloring. It’s similar to the adult coloring books all my roommates have.”

At the nearby printing table, Adam Jiang hand-rolled a print of his carving. The junior, who is concentrating in biomedical engineering, had broken away from the assigned monkey shape to carve his own design of a penguin, a favorite from family art projects.

Jiang, who signed up for “The Art of Looking” at the suggestion of his girlfriend, Eileen Feng, said the class has given him “a different perspective” on the world.

“Science is why things are. You know why air flows so fast from a series of equations or problems. This gives you a good sense of what is framing it. Engineering is often missing the ethical or human component.”

After an hour of cutting and printing their miniature creations, the group moved to the Art Study Center, where a curator had set out more than 30 fine art woodblocks and ink prints, including a early 16th-century woodcut of a rhinoceros by Albrecht Dürer and a Winslow Homer engraving titled “The Army of the Potomac — Our Outlying Picket in the Woods.”

After spending a few minutes observing all of the objects, the students picked individual pieces for longer, in-depth study. Jake Hummer found himself captivated by Gustav Kruell’s “Francis James Child,” a woodblock portrait of the 19th-century Harvard scholar.

“Almost every hair is drawn,” Hummer said.

Gin nodded, adding: “It’s good you have a magnifying glass because you start to see different textures on the page that come from woodblock printing.”

The students moved along the wall to view a series of small engravings used as bookplates, and a group of Japanese prints with translucent elements reflecting the influence of Western optical instruments in Asian art starting in the mid-1800s.

“Next week we’re going to look at a single painting for an hour,” Gin told the students. “You’ve warmed up your looking muscles.”