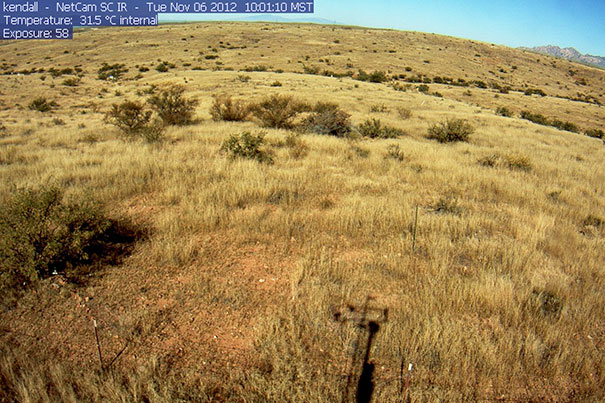

To understand the effects of climate change on grasslands, researchers created a model of both the hydrology and vegetation of the region, then “trained” it using present-day data gathered from the PhenoCam Network, a collection of 250 Internet-connected cameras that capture images of local vegetation conditions and greenness every half hour.

Credit: PhenoCam Network

The shifts from climate change

Longer growing season would offset grassland adaptations, study says

Grasslands across North America will face higher summer temperatures and widespread drought by the end of the century, according to a new Harvard study on the effects of climate change.

But those negative effects will be largely offset, the study predicts, by an earlier start to the spring growing season and by warmer winter temperatures.

Led by Koen Hufkens, a postdoctoral fellow working in the lab of Andrew Richardson, associate professor of organismic and evolutionary biology, a team of researchers developed a highly detailed model that allows researchers to predict how grasslands from Canada to Mexico should react to climate change. The model is described in a paper in the Feb. 29 issue of Nature Climate Change.

Overall, what happens is “the growing season gets split into two parts,” Hufkens said. “You have an earlier spring flush of vegetation, followed by a summer depression where the vegetation withers, and then at the end of the season, you see the vegetation rebound again.”

“The good news is that total grassland productivity is not going to decline, at least for most of the region,” Richardson added. “But the bad news is that we’re going to have this new seasonality that is outside of current practices for rangeland management, and how to adapt to that is unknown.”

To understand the effects of climate change on grasslands, Hufkens and colleagues created a model of both the hydrology and vegetation of the region, then “trained” it using present-day data gathered from the PhenoCam Network, a collection of 250 Internet-connected cameras that capture images of local vegetation conditions and greenness every half hour.

Using 14 sites that represented a variety of climates, Hufkens ran the model against a metric of image greenness to ensure it could reproduce results in line with real-world observations.

“These were sites from across North America, from Canada to New Mexico and from California to Illinois,” Richardson said. “We were using the greenness of the vegetation as a proxy for the activity of that vegetation. We were then able to run the model into the future at a fine spatial and temporal scale.”

That spatial scale — the region was divided into thousands of 10-square-kilometer blocks — allowed researchers to spot important regional differences in the response to climate change.

“That allows us to look at how patterns emerge in different areas,” Hufkens said. “We can say where it happens and when it happens. Other studies roughly predict similar trends, but the intricate spatial and temporal details, which can have implications for the appropriate management response, are often lacking.”

Importantly, Richardson said, the model also works at a very fine temporal scale, using a daily time step rather than a monthly one.

A view of the same field in summer and winter.

Credit: PhenoCam Network

“Grasslands are different from forests in that they respond very quickly to moisture pulses,” he said. “Koen’s model takes advantage of that. By running the model at a daily time scale, it can better represent those patterns.”

The model’s results could present large challenges for those who rely on predictable seasonal changes to manage the landscape, like farmers and ranchers. “These shifting seasons will present new tests for management practices,” Richardson cautioned.

“In higher-elevation grassland … they’re going to benefit because they will see more production. But low-lying grasslands, they will have to think carefully about the costs and benefits,” Richardson said.

For southern grasslands, the increases in production and the losses due to higher summer temperatures should largely balance out while increasing the variability within the growing season, Hufkens said, meaning ranchers could face large challenges.

Though the results suggest climate change may have some positive effects, both Hufkens and Richardson warned that those are the result of a highly delicate balance.

“One message here is simply that the effects of climate change may be somewhat counterintuitive,” Richardson said. “It’s getting more arid, and that’s causing more intense summer droughts. But because of a changing seasonality, vegetation growth is shifting, and those negative effects of drought on ecosystem production can be offset. But that then raises these new questions about appropriate management responses. Relying on this increase in productivity, or expecting that climate change will have long-term benefits because of results like this, is like playing the lottery — the odds are not very good.”