Breaking bonds of time

Indigenous art in ‘Everywhen’ makes claim on the present

Time is relative. Not only in Einstein’s theory but in cultural terms, as well. As “Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia,” a special exhibit at the Harvard Art Museums, illustrates, time may be seen as cyclical — divided into seasons, each with their practical and ceremonial markers — or as a continuous present, in which past and future both play necessary roles.

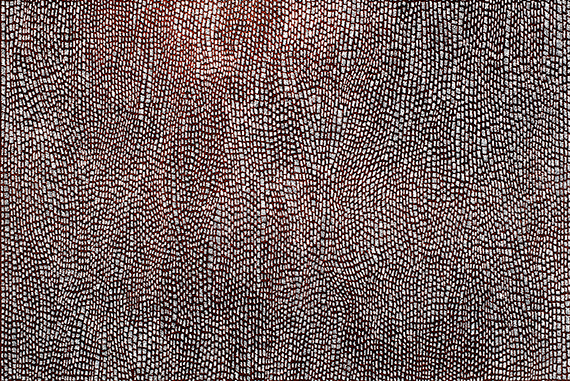

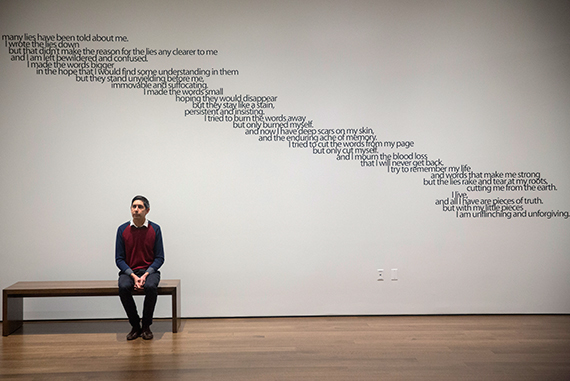

The exhibit progresses through rooms focusing on seasonality, transformation, performance, and remembrance. Consisting primarily of pieces done since 1970 — fitting the Western definition of “contemporary art” — it includes paintings made with acrylic and canvas as well as traditionally sourced ochre and bark, along with text, photographs, and cultural objects such as coolamons (carrying vessels). This allows for the juxtaposition of such pieces as Tom Djawa’s ochre-on-bark “The Burala Rite,” which uses the traditional colors of yellow, white, red, and black, with the stark textual installation of Vernon Ah Kee’s “many lies.”

Such placement is central to the concept behind the exhibit. With 40,000 years of their own history, the indigenous peoples of Australia view the rise of European cultures — and their colonization of the continent — as merely a blip. Too often, however, it has overshadowed a rich and thriving culture.

“The idea of time really came as a kind of corrective to this idea that there is this category of indigenous art that exists as the primitive,” said guest curator Stephen Gilchrist, a member of the Yamatji people of the Inggarda language group of Western Australia. Citing such common usages as “pre-Colombian” and “Indian ruins,” he noted that too often the creations of indigenous peoples are dismissed as anthropological curiosities, rather than art.

“We also have a claim to the present and the past and the future,” said Gilchrist. “Colonization is not the meta-narrative of indigeneity.”

Indeed, said Gilchrist, indigenous people have long supported concepts that are only now being recognized by Euro-centric civilizations, including local and political ecologies and the interconnectedness of life on earth. “There’s an active social agenda to many of these works,” said Gilchrist, referencing the need to make space for alternative narratives. In this way, he said, the struggles of indigenous peoples mirror the efforts of such movements as feminism and Black Lives Matter.

Even the assembly of the exhibition served as an eye-opener. Narayan Khandekar, a senior conservation scientist and director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, traveled with Gilchrist to several regional art centers: Waringarri in Kununurra in Western Australia, Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre in Yirrkala, and Tiwi Designs on Bathurst Island, part of the Tiwi Islands.

“It was great to see the process from the very beginning,” said the conservator. “From the collecting of the ochre to seeing how the ochre is prepared to how the artists use different binding media.” (Under Khandekar’s direction, the Straus Center has launched a large-scale technical examination of indigenous Australian bark paintings.)

Even the distances covered helped the conservator understand the difference in perspective. “When Stephen and I went traveling to art centers I realized that what we call remote is only from our point of view, living in cities. We’re coming from a remote place to them,” said Khandekar.

“The combination of art and politics is a really fascinating and heady mix,” added Gilchrist. “I think what people respond to with indigenous art is that it’s free from irony. It’s from this deeply felt place of belonging and thinking about history. It has a basis in truth.”

“Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia” is on view Feb. 5-Sept. 18 at the Special Exhibitions Gallery, Harvard Art Museums. A conversation with curator Stephen Gilchrist and artist Vernon Ah Kee will take place in Menschel Hall on the lower level on Thursday, Feb. 4. Before the talk begins at 6 p.m., visitors will have an opportunity to view the exhibition. The museums will also remain open after the discussion; lecture attendees are invited to return to the galleries as well as enjoy a reception in the Calderwood Courtyard. Admission is free but tickets for the lecture are required. Tickets (limit two per person) will be distributed after 5 p.m. on the lower level on a first-come, first-served basis. The lecture hall doors open at 5:30 p.m.