For Harvard professors, these are a few of their favorite things

What inspires you, captures your imagination, or just imbues beauty for you? The Gazette recently asked six Harvard professors to discuss their favorite objects, which included one of the earliest printed books, a three-dimensional model of a crystal, a hand-carved wooden bowl, and a plastic bag filled with sand. The varied items have deep personal and professional connections to these faculty members, and offer glimpses into their lives. Here are descriptions of their eclectic items and explanations of why they hold deep meaning.

Giuliana Bruno

Emmet Blakeney Gleason Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies

It’s happened to many of us. We pass an object for years without it registering. Then one day we stop and see it clearly for the first time.

For decades, Giuliana Bruno passed a portrait in her parents’ home in Naples, Italy, without paying it much thought. Then, as she began to pack up their belongings several years ago, she suddenly saw the picture “with different eyes.”

Its beauty, and its scars, captivated her.

The portrait, done on wood, is by her grandfather, the artist and architect Luigi Bruno. It depicts a young woman resting in a red chair, her pensive gaze drifting out past the viewer to some unknown horizon. Bruno, Emmet Blakeney Gleason Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies, came to love the painting’s imagery, in particular the mystery behind the young woman at its center. “It’s the ambiguity about this female character that I find endlessly intriguing,” she said, “and I like the expression on the face, this kind of melancholic absorption.”

She also loves its connection to the past.

“I can still feel the touch of my grandfather’s hand on this wood and the way in which he delineated the contours of this body.”

Bruno’s choice not to restore the painting’s scratches and cracks, even a perfectly round hole drilled by a termite into the young woman’s right eye, is intentional. Those small flaws tell their own stories, she said.

“The object contains within itself the mark not only of the person that’s made it, but the mark of the life of the object, and the circulation that it had.”

Something else speaks to how the painting once moved through the world: Its reverse side is covered in color, with red, yellow, and blue splashes of paint in what was once her grandfather’s working palette.

“That’s why I love this painting particularly … it gives you a wonderful sense of how it was part of a process.”

“It’s in the pigments, in the colors, in the texture, in the way in which it has also faded over the course of time,” Bruno added, “that the materiality of this relationship between myself and my grandfather takes place across an ocean and a century of life.”

Ken Rogoff

Professor of economics and Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy

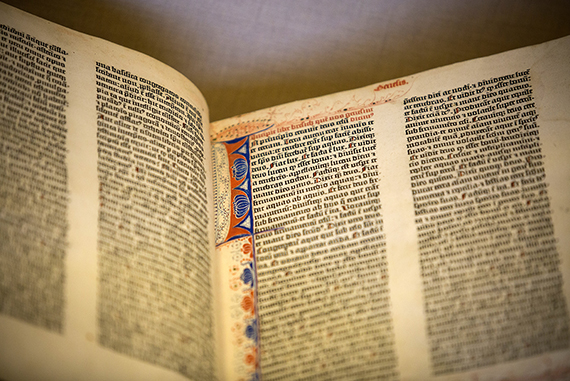

Economist Ken Rogoff likes to revisit one of the most famous items in the Harvard collection: Johann Gutenberg’s 1454–55 Latin Bible. The large, rare book is displayed under glass behind a velvet rope in the Widener Room, the space in the library of the same name dedicated to the memory of young Harvard graduate Harry Elkins Widener, who died during the sinking of the Titanic while returning from a book-buying trip to Europe.

-

Ken Rogoff, Harvard’s Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and professor of economics.

Rogoff finds the volume so appealing in part because of how it opened the world to an exchange of information. “The Gutenberg Bible represents one of the transformational periods in the modern era; it’s really like the Internet for the medieval period,” he said of the first major work printed in the West using movable metal type. He is also drawn to the book’s beauty, its vivid text, and its evocative, illuminated pages.

“It’s surprising that they could produce something of such elegance and grace and grandeur so long ago,” Rogoff said.

He first saw a copy as a freshman at his alma mater, Yale University, but he likely first heard about the Bible as a teen, he said, in connection with another one of his passions: chess. Among the earliest books ever printed was the Spanish chess player Luis Ramírez de Lucena’s 1497 chess book that helped to unify the rules of the game around the world, said Rogoff, who is also a chess grandmaster.

“It could well be that’s how I first heard about the Gutenberg Bible, because I was probably 13 when I learned about the Lucena Position. I could not believe that someone had published such a clever idea so long ago.”

And while Yale’s copy is beautiful, said Rogoff, the history of Harvard’s volume makes it even more special to him.

“It’s very intimately connected to Harvard, not just a possession, but something with such a great back story that is so much part of Harvard history.”

Jamaica Kincaid

Professor of African and African-American studies in residence

She thinks it might have been during her childhood, as she played on her native island of Antigua and imagined the landscape absent of azure water, as if she had pulled a giant plug and drained the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, that the vision of a desert first struck Jamaica Kincaid.

“It’s possible that I wondered what it would look like when the water ran out … because that’s what the desert looks like, as if the water ran out.”

Today she finds a desert thrilling, with its desolate, stark beauty, and its harsh conditions that on rare occasions usher forth a rich plant life.

“I love the desert,” said Kincaid, who used to live in California and made regular pilgrimages to the Mohave Desert to see the places where it meets the Sonoran Desert. “In the spring, sometimes there’s a sudden rainfall, and it will just bloom in places that don’t bloom for years.”

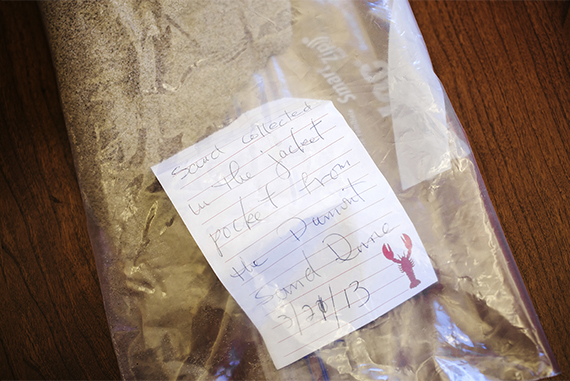

In her desert travels she has discovered dead volcanoes, lava fields, and a 50-mile-long sand dune that produced her favorite object: a plastic bag of sand.

“Often I will tell someone, ‘Let’s go out into the desert,’ and I can see they didn’t know I was that kind of person,” she said, laughing.

But on March 21, 2013, she was with a longtime friend who knew Kincaid was exactly that kind of person and who likely didn’t blink when the writer climbed up one of the Mohave’s Dumont Dunes, and then slid all the way back down.

In the process, Kincaid’s coat pockets filled with sand. She discovered the stowaway grains back at home, and kept them as a memento. Today, the plastic bag, filled with multicolored sand, darkened by countless tiny black volcanic granules, sits on a shelf in her bright Barker Center office.

“I see it every day; it’s next to my bust of Karl Marx,” said Kincaid, pointing to the bag that includes a small note about where the sand came from and the date.

“It certainly serves to bolster my memory,” she added. “I work a lot from memory, so it will be one of the things that will lead to something, that will lead to something else.”

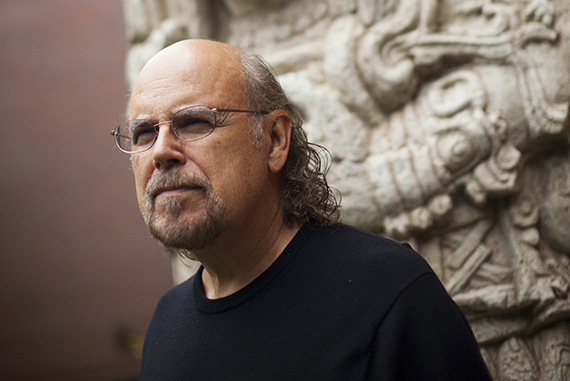

Davíd Carrasco

Neil L. Rudenstine Professor of the Study of Latin America

Davíd Carrasco’s favorite object links three literary giants: Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel García Márquez, and Toni Morrison. It also evokes his heritage.

“A Mexican-American deals not just with the physical bridges between countries and cultures,” said Carrasco, Neil L. Rudenstine Professor of the Study of Latin America at Harvard Divinity School. “You yourself are kind of a walking bridge of language, race, and the imagination.”

As such, he helped to jump-start a profound connection between two Nobel laureates.

-

Davíd Carrasco, Neil L. Rudenstine Professor of the Study of Latin America at Harvard Divinity School.

Carrasco and Morrison met at Princeton University and quickly became friends. In 1995 he invited her and her son Ford on a trip to Mexico City to explore some of the archaeological projects he’d been working on. She accepted, and asked if he could introduce her to García Márquez.

“I said ‘certainly,’” recalled Carrasco. “In fact, I didn’t know him at the time, but I knew Carlos Fuentes, the great Mexican novelist and essayist. Carlos said, ‘David, you are in luck. Gabo is my best friend, and we’ll have a dinner at my home!’”

“Gabriel García Márquez was very taken with Toni Morrison,” recalled Carrasco, “and Toni Morrison was very pleased to spend the evening with [him] and Fuentes.”

A studied politeness between García Márquez and Morrison turned into a midnight hour of the Nobel Prize-winners trading stories and jokes and sharing their literary influences and inspirations with help from an interpreter. Morrison told Carrasco she treasured the evening as much as her trip to Stockholm to receive her Nobel.

García Márquez later visited Morrison at Princeton and joined one of her seminars. “As time went on, observing them talk and visit together I had the feeling that he really developed a crush on her, it was clear,” said Carrasco.

-

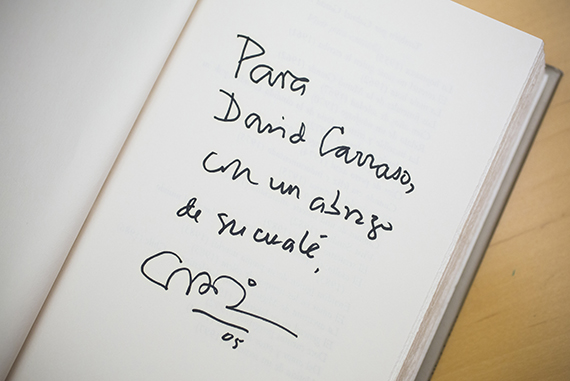

The inscription in Davíd Carrasco’s copy of “Vivir para Contarla,” or “Living To Tell the Tale,” reads: “Para David Carrasco, con un abrazo de su cuate, Gabriel García Márquez,” or “For David Carrasco, with an embrace from his buddy, Gabriel García Márquez.”

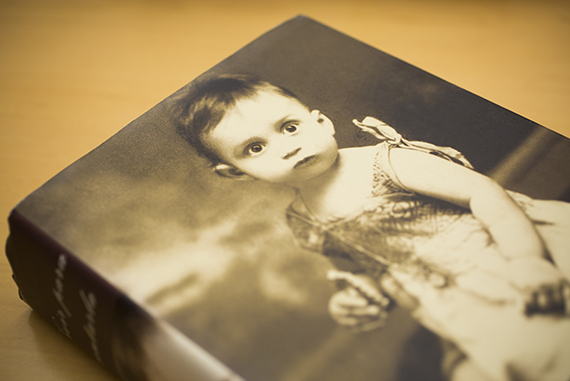

Carrasco helped to organize another meeting between the two writers in Mexico City in 2005. During lunch, each wrote a private message on a cloth napkin and gave it to the other as a gift. García Márquez also signed Carrasco’s copy of “Vivir para Contarla,” or “Living To Tell the Tale,” the Colombian author’s autobiography.

The inscription reads: “Para David Carrasco, con un abrazo de su cuate, Gabriel García Márquez,” meaning “For David Carrasco, with an embrace from his buddy, Gabriel García Márquez.”

“I think it shows his affection for me, and his appreciation for the fact that I was a bridge,” said Carrasco, “a living bridge between him and Toni Morrison.”

Evelyn Hu

Tarr-Coyne Professor of Applied Physics and of Electrical Engineering

Applied physicist and electrical engineer Evelyn Hu, whose research explores light at the nanoscale level, bioinspired materials, and other areas that “demonstrate exceptional electronic and photonic behavior,” brings her object to class.

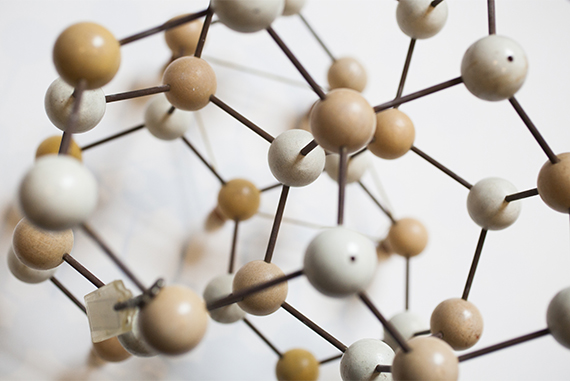

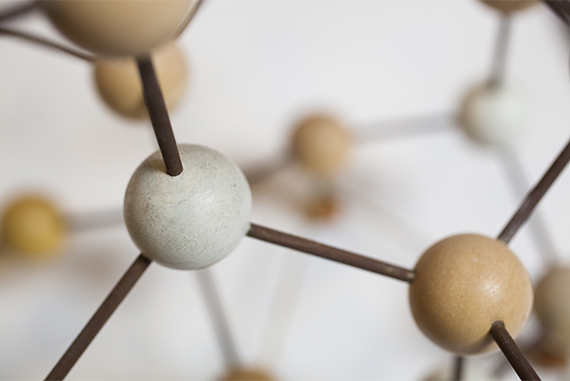

Getting your mind around the type of tiny matter familiar to Hu can be tricky. So she regularly trots out a favorite visual aid for undergraduates. Her fall course has examined the fundamentals behind semiconductor devices, lasers, transistors, light-emitting diodes, and solar cells, and it requires “understanding how electrons live in a material,” said Hu.

Her three-dimensional model of a gallium arsenide crystal called a “zinc-blende” structure helps her students to imagine the world of charged particles swirling in and around atoms, she said. The roughly six-inch-high model consists of gallium and arsenide atoms represented by small, faded white and beige wooden balls that are connected by short, slightly rusted bars of metal, signifying electron bonds.

The small teaching tool might help students to “focus their thoughts,” said Hu. She points to the model and tells her class to “imagine you are an electron and you are traveling through this crystal. What would you see as you travel through the variations of ‘landscapes’ set by these atoms? Imagine the hills and valleys that these atoms make up in that crystal.”

“I like going beyond the board and the PowerPoint,” said Hu, adding, “The model helps me visualize what I’m talking about, too.”

She admits that many of her Harvard co-workers own fancier, more-sophisticated models, but she would never trade in her aging crystal. She loves its simplicity and its provenance. It originally belonged to her colleague Jim Mertz, a Harvard graduate, who recruited her to the University of California, Santa Barbara. While there, they collaborated with colleagues from the electrical and chemical engineering and physics departments to develop an integrated program based on compound semiconductors such as gallium arsenide.

“It engaged us all in exciting research that grew the programs and the promise, and so this crystal is symbolic of all of that.”

Donald Pfister

Curator of the Farlow Library and Herbarium of Cryptogamic Botany and Asa Gray Professor of Systematic Botany

It seems fitting that Harvard’s resident fungi specialist with a passion for trees should choose an object that combines both of these interests.

Donald Pfister’s favorite item is personal, but it has deep ties to his life’s work. On a rainy fall afternoon in the Harvard University Herbaria’s Farlow Reference Reading Room, Pfister, the Asa Gray Professor of Systematic Botany, showed off one of his more than 20 handcrafted wooden bowls.

“When I see them, I just can’t help myself,” said Pfister, who has been collecting the bowls for years. He said his first was likely utilitarian in nature, “for making salad. And then you begin to realize they are much more than that.”

The design of this particular bowl, a gift from the Harvard College staff following his year as interim dean in 2014, involves an intricate pattern that almost resembles a landscape at sunrise or sunset. But what looks like the work of a talented painter is actually the work of one of the most talented artists of all: Mother Nature.

“This one is made from maple and it’s spalted, which means that it’s got this fungi growing through the wood,” said Pfister, pointing out the bowl’s elaborate markings.

Fungi are often territorial, and when they invade a tree, they cut off the section of the wood they then monopolize “by laying down these tough lines,” explained Pfister, of the bowl’s ink-like marks. “And different fungi create different colors,” he added, noting the varying shades. Together they create dramatic patterns.

The bowl has been part of a recent exhibit in the building on wooden items, and periodically it is used in class.

“It’s an interesting kind of teaching tool for students to help them begin to think about the biology of fungi. Here’s this invasion of the wood … and the mechanism to compete and keep other fungi and other organisms out of that spot.

“And then it’s simply beautiful,” he said. “It makes a pattern that’s so attractive.”