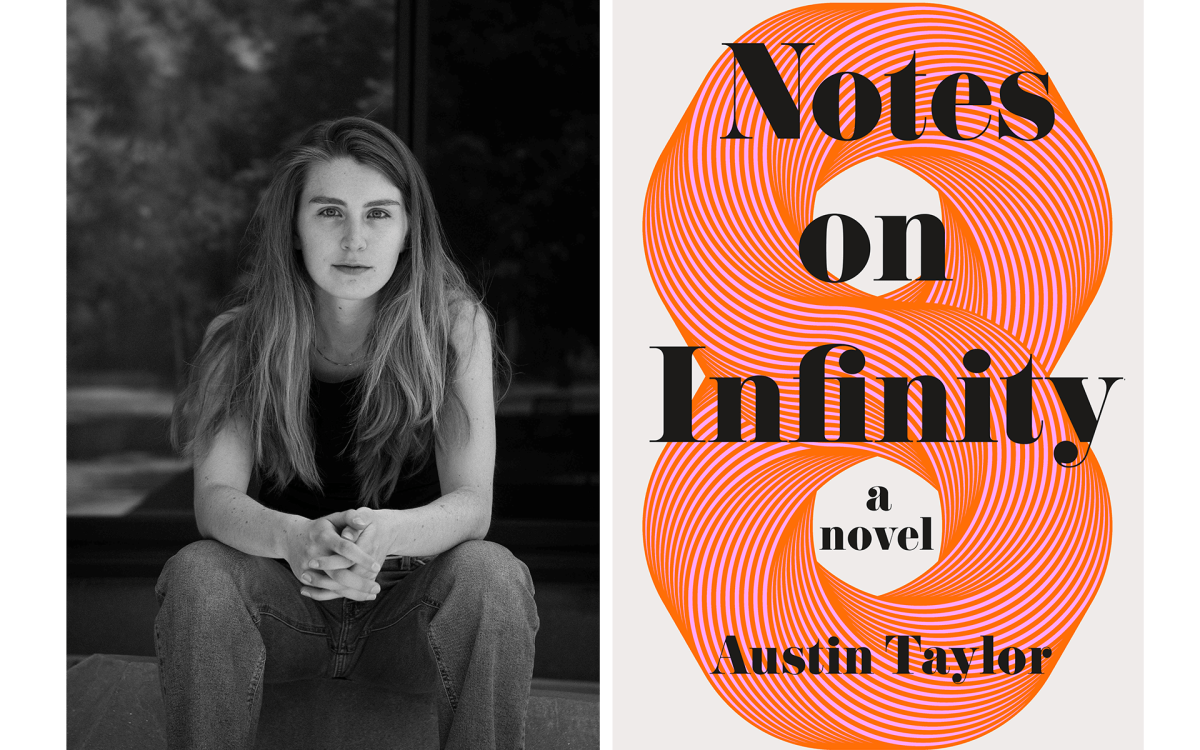

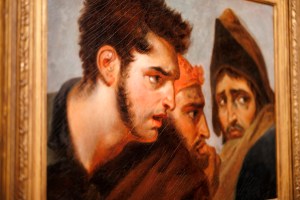

Vera Grant, director of the Cooper Gallery, and “Drapetomania” curator Alejandro de la Fuente in front of one of the exhibit’s many dramatic pieces — ”Resurrection,” created by Rafael Queneditt (photo 1). Adelaida Herrera’s “Neighbors” (photo 2) and Andrés Montalván Cuéllar’s “The Eternal Idea of Return” (photo 3) reflect the African influence on Cuban art as the artists’ work articulates issues of identity and race.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Tangled roots

‘Drapetomania’ illuminates African influence in Cuban art

The story of “Drapetomania: Grupo Antillano and the Art of Afro-Cuba” is one of discovery and rediscovery. For visitors to the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African and African American Art, it’s a stunning find, tucked away in the former commercial space that reopened as the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research last fall. For the 30 artists represented, it illustrates the uncovering of an artistic heritage, and a lineage that was long denied.

That heritage — the African influence on Cuban art — comes from the Grupo Antillano, a group of 16 free-thinking Cubans who chose to celebrate and explore their culture’s long-denigrated African roots roughly 30 years ago. Three decades later, these artists, whose work makes up about half the show, have been reintroduced to contemporary Cuban artists, many of whom had rejected the idea of an Afro-Cuban heritage in favor of something seemingly more universal — or European — and forward-looking.

“There were different visions of what constituted ‘real art,’ ” explained the show’s curator, Alejandro de la Fuente, the Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin-American History and Economics and a professor of African and African-American studies and of history. De la Fuente approached these younger artists to discuss the possibility of a joint show, in some cases introducing them to Grupo Antillano.

Once they had seen the work, he said, they were eager to participate. Speaking of Belkis Ayón and José Bedia, younger artists whose large-scale pieces line the opening hallway of the exhibit, “they both conveyed to me that they didn’t quite get how hard it is to articulate issues of identity and race,” he said. “It was quite a happy moment.”

These issues — specifically, Cuba’s history with Africa and slavery — were central to Grupo Antillano, whose foundational manifesto (displayed at the gallery in both Spanish and English) discusses the importance of the African diaspora, racism, and colonialism in Cuban art. The multi-ethnic and mixed-gender group originally converged in 1978 around the work of Wifredo Lam, a Cuban surrealist who made his name in Paris before returning to his home country. It dispersed in 1985, three years after Lam’s death, to be largely erased from official accounts of Cuba’s culture.

“To me, the mystery is, how do you erase so much creativity?” said de la Fuente. “How do you forget?”

“Drapetomania” may not answer those questions, but it does bridge the gap. Several pieces — including Bedia’s triptych, “El Rompimiento/El Amarre/El Pataki”/”The Break, The Tether, The Fable” — were created for this show. Responding to the older group’s manifesto, it explores the victimization — and sexualization — of Africans, its graceful black figures set against a blood-red background.

Materials as well as subjects refer back to the earlier group, and beyond. Wood, for example, is a common medium. The original group used it as a throwback to Africa and an evocation of community. “Vecinos”/“Neighbors,” a 2004 work by Grupo Antillano member Adelaida Herrera, features a wooden shutter painted in soft, weathered colors. Stuck into the shutter’s flaps are notes, a bit of coffee, and ration cards, reflecting the reality of Cuban life. In the hands of Andrés Montalván Cuellar, one of the younger artists, the organic medium becomes “Eterna Idea del Regreso”/”The Eternal Idea of Return.” In this evocative sculpture, faceless cutouts of men, their bodies barely sketched in, are slammed together around a central coffin- or (ship-) shaped object. Without being overly literal, it evokes the dehumanizing Middle Passage of slavery.

This legacy provides the name of the show. Drapetomania, de la Fuente explains, was the name of a “disease” discovered by a doctor on a Louisiana slave plantation. Only found among enslaved Africans, its symptoms were “that they ran away,” he said. “That they wanted to be free.”

Such yearning can be seen in “Resurreccion”/”Resurrection,” a piece created for the show by original Grupo Antillano member Rafael Queneditt. From the front, the life-size mixed-media sculpture shows a Catholic angel, painted with the red, white, and blue of the Cuban flag, aspiring and patriotic. Step around back and it becomes clear that the cross that serves as the angel’s backdrop is composed of a slave’s stock and shackles, the instruments of torture hung from the beautifully finished wood like jewelry. At its base, a Yoruba figure sits between two candles, a memory of other roots and, perhaps, an older faith.

This, said de la Fuente, is “the true face of Cuba. The Cuba you don’t see.”

As part of “Drapetomania,” the Cooper Gallery is also presenting a Cuban film series, with screenings on Thursdays at noon. The exhibit runs through May 29.