Honoring, and feeling, Heaney’s presence

Suite dedicated to Nobel Prize-winning poet who called Adams House home

When Seamus Heaney won the 1995 Nobel Prize for literature he was traveling in Greece, but that didn’t stop him from dialing his extended Harvard family thousands of miles away.

Soon after hearing the news Heaney called his friends at Adams House, his home during his stints as a visiting professor at Harvard beginning in 1979, as the Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory from 1984 to 1995, and as the Ralph Waldo Emerson Poet in Residence, a position he held until 2006.

“He phoned to say he couldn’t keep the astonishing news to himself,” Bob Kiely, Adams House master from 1973 to 1999, said during a moving tribute to Heaney at Memorial Church in November 2013, three months after the poet’s death. “It was during a tea, so I announced to the assembled crowd of students, who cheered so lustily he could hear them in Athens.”

Heaney’s spirit lives on in his suite in Adams House, dedicated in a ceremony on Saturday that brought together family, friends, and poetry lovers to remember the artist and the man.

“He just touched everybody,” said Adams House Master Sean Palfrey in an interview before the service. “He was both a poetic and a gentle person … engaged in all parts of life.”

“The idea came to me that we should celebrate the kind of person he was, not just his poetry, but the humanity and the warmth and the humor of the man,” Palfrey added, “and just put the suite aside.”

Palfrey, who had the blessing of Heaney’s widow, Marie, envisioned a quiet space where students could work and “write creatively,” free from interruptions or the pull of the Web.

That vision matched Heaney’s own. When he began traveling to Harvard 1979, the poet wanted a simple place to live and work, one that was close to his classrooms and Harvard Square. He found it on Plympton Street in suite I-12 at the top of a winding flight of stairs.

“The arts and bohemia were well-represented” at Adams House, Heaney told the Gazette in 2012. “It was a desired address.” In his time at the House, Heaney penned two Harvard-inspired works: “Villanelle for an Anniversary,” which he composed in honor of the University’s 350th year, and “Alphabets,” written for the Phi Beta Kappa Literary Exercises in 1984. “Traditionally the Phi Beta Kappa poem is about learning,” Heaney said in 2012. “So mine was [about] making the first letters at primary school.”

For Heaney, composing in Cambridge sometimes came second to teaching, reading, and connecting with students and colleagues. He was “always open to sitting with the students and reading poetry,” recalled Palfrey. He was also a regular at the House dining hall, often with Marie, when she was in town, by his side. They attended Adams House teas; he read poetry, she sang and told stories.

The suite, a modest two-bedroom, came with a welcoming view of the courtyard and a tree Heaney liked to climb, a fireplace, and a quirky door that doubled as a desk. According to Palfrey, one of the suite’s doors had come loose from its hinges and Heaney took to using it as a writing space. Palfrey contacted an alumnus who works with reclaimed wood and asked him him to fashion the table in the shape of a door that now sits before the suite’s courtyard-facing windows.

Unlocking the Heaney suite

A shot of Northern Ireland by the photographer Rachel Brown hangs above the fireplace in the Seamus Heaney suite. Brown collaborated with the poet on the book “Sweeney’s Flight,” which matches her vivid photos with extracts and quotations from “Sweeney Astray” — Heaney’s translation of the medieval Irish work “Buile Suibhne.” Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Greeting visitors at the suite’s entrance is a bronze bust of Heaney by sculptor Carolyn Mulholland, donated by American diplomat and former United States ambassador to Ireland Jean Kennedy Smith and Harvard Law School graduate Joseph Hassett and his wife, Carol Melton.

A close-up of the mantle in Adams House’s Seamus Heaney suite, which administrators, faculty, and students helped transform into a quiet, reflective space in honor of the late poet.

According to some, Seamus Heaney used an unhinged door from the suite as a desk. To keep the tradition alive, Adams House Master Sean Palfrey had a table made to look like a door for the refurbished suite.

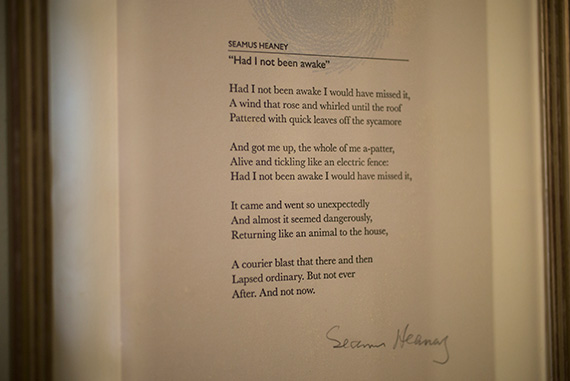

Framed broadsides of several of Seamus Heaney’s poems hang on the walls of the newly dedicated suite, including this one, “Had I not been awake,” which was signed by the poet.

Works by the Irish poet and many others fill the Seamus Heaney suite in Adams House.

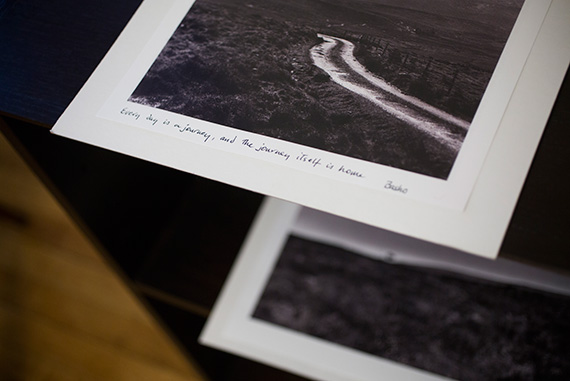

Pictures of the Irish countryside offer visitors a look at the evocative landscape that inspired the sense of place reflected in much of Seamus Heaney’s work.

A view of Apthorp House from the windows of the Seamus Heaney suite in Adams House.

A picture of the late Seamus Heaney graces one of the walls in the Adams House suite that was recently dedicated in his honor.

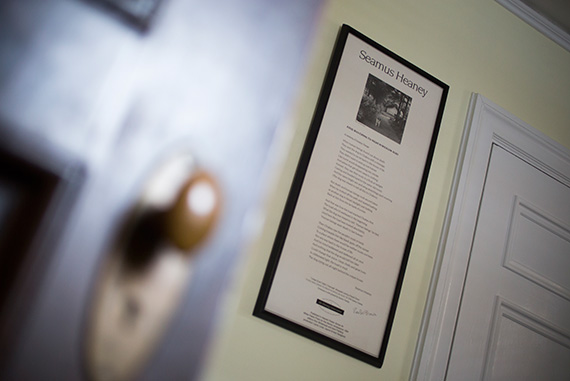

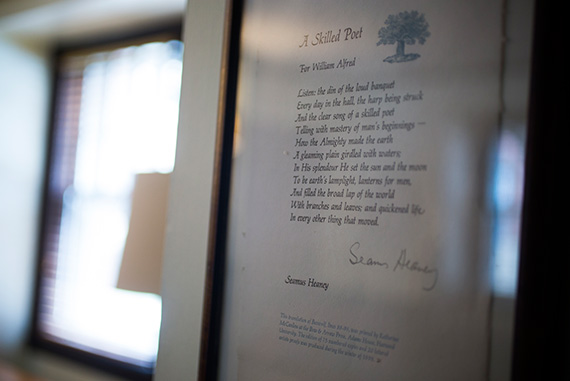

Framed broadsides of Seamus Heaney’s poems cover the walls of the suite in Adams House.

Work on the walls in the Seamus Heaney suite includes these several lines of the poet’s translation of “Beowulf” that were printed at the Adams House Bow & Arrow Press.

Seamus Heaney’s widow, Marie, sits in the Adams House suite where she used to visit him during his stints at Harvard.

Two sconces cast a gentle glow in the main room, a request from students who asked that the overhead light be removed to make it look “less like a dorm room.” Fittingly, the walls are covered with several illustrated broadsides of Heaney’s work, including the Harvard villanelle and the last stanza of “Poet’s Chair,” which is topped by a linoleum block print by Heaney’s friend, the Harvard professor and artist Dimitri Hadzi (1921-2006).

The poem’s final section conjures up themes familiar in Heaney’s work: his youth in Northern Ireland, his family, his turning to and returning to language, and his hope. Its last lines read: “Of the poem as a ploughshare that turns time / Up and over. / Of the chair in leaf / The fairy thorn is entering for the future./ Of being here for good in every sense.”

The piece was named after a chair by the Northern Ireland sculptor Carolyn Mulholland. Nearby, Mulholland’s bronze bust of Heaney greets visitors as they enter.

Other flourishes in the space include a CD player and a box set of Heaney reading his collected poems, shelves of books by Heaney and other authors, and a smiling photo of the poet, arms crossed, opposite a mirror image of Marie, both taken by Palfrey. One of the suite’s small bedrooms has been transformed into a meditation space with two chairs.

“He would have loved it,” Marie Heaney said of the suite. “It’s exactly the sort of thing he would have loved. I know that.”

The reworked space, she said, is “a place for withdrawal, which of course it was for Seamus. He could go and lock himself in there, which he would do from time to time, possibly not often enough, because he gave a lot to everybody. He was incredibly generous-spirited.”

The suite was opened months before the official dedication, and has already hosted talks and poetry readings, along with countless students in search of quiet. Santiago Pardo ’16 has visited several times in recent weeks to prep for papers and exams.

“Here at Harvard we have a lot of workspaces, we have a lot of places to write your papers, to read, and sometimes the atmosphere of those places is terrible; just the constant tapping, you almost feel the stress as you hear a phone buzz or the keyboard click,” said Pardo. “This is a different kind of work space … I think we’ve summed it up quite nicely in saying it’s not high tech, but high touch.”

A sign on a shelf near the door discourages cellphone use. Computers are allowed, but Palfrey and others hope visitors will unplug as much as possible, and opt instead for paper and pen, Heaney’s preferred tools when drafting a poem.

Helen Vendler, the A. Kingsley Porter University Professor, helped select various items for the refurbished suite. She said the rooms give students a chance to delve into Heaney’s work, and their own, uninterrupted “by the din of sound systems, laptops, cellphones, roommates, and conversation.”

Vendler’s memory of her first encounter Heaney vividly captures his spirit. She was lecturing at the Yeats International Summer School in County Sligo in August 1975 when she heard a young Irish poet read a selection of “electrifying poems.” When she approached him with questions, Heaney happily offered to discuss his work with her the following day, handing over his galleys from a new volume, “North,” to review before they met.

“It was typical of his generosity to all that he’d give over his galleys and explain things to this unknown woman,” Vendler recalled in an email. “I went home and wrote for The New York Times about ‘North’ — one of the 20th-century volumes able to stand with such landmarks as Lowell’s ‘Life Studies’ and Stevens’ ‘Harmonium’ as marking out new inventive moves for lyric, as well as urgent subject matter. Seamus and I remained friends until he died.”

Marie Heaney and her three children traveled to Cambridge after her husband’s death for the service at the Memorial Church, but ,“We were numb,” she recalled, still overwhelmed by the loss. The dedicated suite has “brought Cambridge back to us in a positive way,” she added, “retrieved it in some way, and I am very grateful for that.”