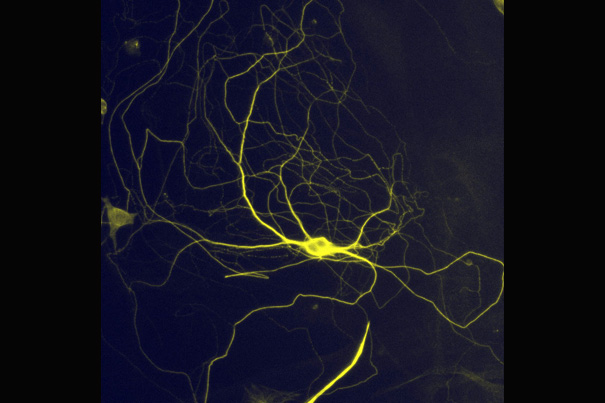

Harvard researchers have successfully converted mouse and human skin cells into pain-sensing neurons. The neurons respond to a number of stimuli that cause acute and inflammatory distress.

Credit: Liz Buttermore

Creating pain-sensing neurons

Stem cell researchers manage to formulate them out of skin cells

After more than six years of intensive effort, including repeated failures that at times made the quest seem futile, Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH) and at Harvard’s Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology (HSCRB) have successfully converted mouse and human skin cells into pain-sensing neurons that respond to a number of stimuli that cause acute and inflammatory distress.

This “disease in a dish” model of pain reception may advance the understanding of different types of pain, identify why individuals differ in their pain responses or their risk of developing chronic pain, and make possible the development of improved drugs to treat pain. A report on the work was given advance online release today by the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Clifford Woolf, co-director of HSCI’s Nervous System Diseases Program, led the research effort. Postdoctoral fellows Brian Wainger and Liz Buttermore are first authors on the journal paper. Woolf’s collaborators on the project included Lee Rubin and Kevin Eggan, both professors in HSCRB.

The neuronal pain receptors created by Woolf and his team reportedly respond to both the kind of intense stimuli that are triggered by a physical injury and that cause “ouch” pain, and the more subtle stimuli triggered by inflammation, which results in pain tenderness. The fact that the neurons respond to both the gross and fine forms of stimulation that produce distinct pain in humans provides confirmation that the neurons are functioning as naturally developed neurons would, Woolf said.

When the project began, Woolf’s team was attempting to create pain-sensing neurons from embryonic stem cells, but the task proved far more challenging than first envisioned.

“We spent three years trying to recapitulate the developmental steps involved, and it turned out to be a total bust,” said Woolf, who in addition to his HSCI roles is a Harvard Medical School (HMS) professor of neurology and neurobiology, and director of the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at BCH. But the effort to develop pain-sensing neurons was occurring at just the right moment in the evolution of stem cell biology, coinciding with the development of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS) technology, the ability to transform adult human cells into stem cells and then into other forms of adult cells.

The project was the original effort of an ongoing collaboration between HSCI researchers and pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, and, said Woolf, “for the first three years it was a total bust. But they, like us, were in it for the long haul.”

Describing the early days of the project as “hitting our head against a brick wall,” Woolf said that “we had a dogged kind of persistence,” and once the team began attempting to create the neurons directly from mouse and human skin cells, everything began to fall into place.

“We took mature neurons from mice, and found transcription factors that hadn’t been described before,” Woolf said. Then, using five factors — including three previously undescribed factors — the team was able to transform skin cells directly into the pain-sensing neurons.

Asked what kept him pushing through repeated failures to make pain neurons using different approaches, initially starting with human embryonic stem cells, Woolf said, “It’s really complicated, because there are many projects I do pull the plug on, when I can’t see any way out of it. Here, even though we experienced failure constantly, I always felt there was something else we could do that would advance the work. Whether it was worth this long haul, time will tell. I’m optimistic.

“I think the ability to make human pain neurons for the pain field is going to be very important. Furthermore, our failure with embryonic stem cells led us to work with adult tissue samples, making the technology much more clinically relevant, since these are easy to collect [from patients suffering from different kinds of pain],” he added.

Woolf noted that the pain-sensing neurons his team developed “beautifully model” neuropathies and hypersensitivity to pain experienced by some of the patients who donated skin cells to the project. “Many pain conditions are due to genetic mutations, and we can model those beautifully,” Woolf said.