Early experiments in catching the eye

Exhibit illuminates rise of advertising in post-Civil War U.S.

No blame will be assigned if you have never heard of the Massasoit Varnish Works or B.T. Babbitt’s Best Soap. And rest easy if you have forgotten that during the late 19th century, for the modest sum of 50 cents, you could purchase from the New York Dental Co. of 7 Tremont St. in Boston a device for the painless extraction of teeth.

And yet blame and shame are all yours if sometime this month you don’t see “The Art of American Advertising,” an exhibit open through Aug. 1 in the North Lobby of the Baker Library/Bloomberg Center at Harvard Business School. The idea: illustrate the rise in America of artful, profit-making, culture-shaking advertising from 1865 to 1910.

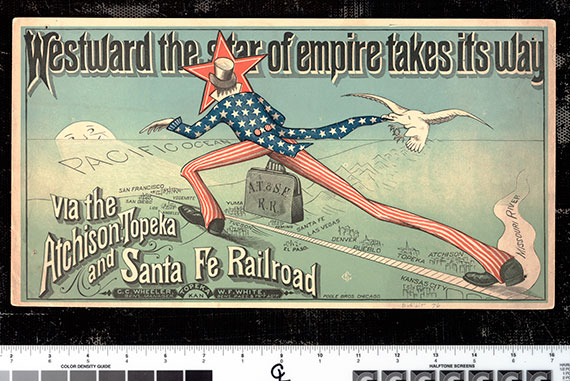

During that period of robust economic growth, a confluence of factors contributed to a boom in how products were advertised for sale. National markets were expanding fast, hastened by a rise in consumer demand. Magazines and newspapers were hungry for advertising. Businesses were beginning to embrace brand recognition to build profits. (Among the exhibit’s nine themes is “A Marketing Revolution.”) And rail systems were growing.

“The railroads had a transformative effect on the U.S. economy,” said Melissa Banta, guest curator at Baker Library Historical Collections, the source of the exhibit’s artifacts. “The industry created the model for the mass production of goods and made possible the mass distribution of those goods.”

At the same time, consumers had more cash. “People’s incomes were expanding,” said Christine Riggle, an HBS special collections librarian who was on the exhibition staff. Would-be customers were also “becoming visually literate,” she added, though photography would not dominate advertising until after 1910.

Advances in printing technologies — better inks, papers, presses, and image-capturing plates — helped drive advertising’s reach and profits. (“A pot of printer’s ink,” The New York Times declared in 1894, “is better than the greatest gold mine.”) The race was on for more and better posters, catalogs, trade cards, brochures, and novelties — the kind of ephemera at the heart of the HBS show and of modern advertising itself.

‘The Art of American Advertising’

“Westward the Star of Empire Takes Its Way,” an Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad poster. Rail systems aggressively expanded after 1865, spurring national markets that, in turn, spurred national advertising. All images courtesy of Baker Library/Harvard Business School.

A Queen City Printing Ink Co. advertisement from The Inland Printer, Vol. 9 (October 1890-September 1891). Advances in printing technology influenced national advertising. As The New York Times noted on Oct. 14, 1894, “A pot of printer’s ink is better than the greatest gold mine.”

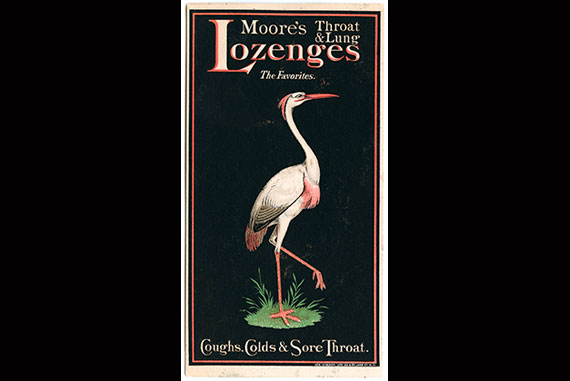

A Moore’s Throat & Lung Lozenges trade card from the Advertising Ephemera Collection at Harvard Business School. Advertisements from 1865 to 1910 could pass as fine art, as some modern analogs might today.

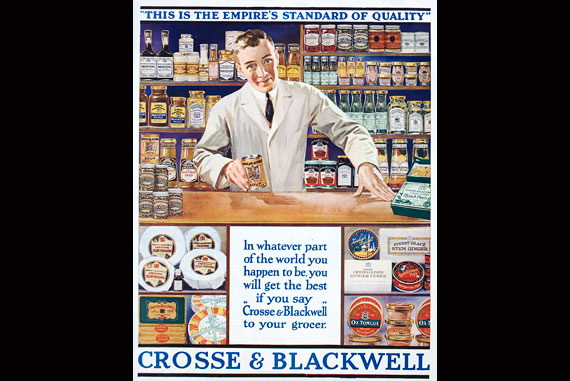

A circa-1920 Crosse & Blackwell advertisement, © Michael Nicholson/Corbis. Branding found new life in modern advertising, sometimes with a global touch.

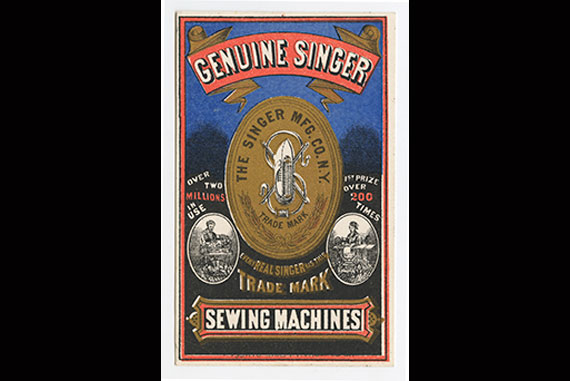

A vintage Singer Mfg. Co. trade card. Many American brands familiar in the 19th century survive today.

“The 19th-century advertising formats and marketing strategies exhibited here are the precursor of everything you see today,” said Banta. Trade cards, testimonials, and brand-name souvenirs still exist, along with the sense that advertising is the first showcase of popular art. Artists, she said, flocked to the medium for the exposure it brought.

At one point, for instance, “advertising posters of locomotives were popular in executive offices, and in this context were considered works of art,” Banta said. Many of these advertisements are so attractive and well done that “art” is a term applied easily. “It was challenging,” she said of choosing images and artifacts for the exhibit. “Every piece was fascinating from an artistic and documentary point of view.”

A lot of 19th-century advertising seems familiar. “A surprising number of companies have survived,” said Banta. A visitor to the exhibit may be puzzled at Boston’s Hinkley Locomotive Works, but will recognize names like Singer (sewing machines), Crosse & Blackwell (sauces), and Domino’s (sugar).

Still, part of the charm of the three-room exhibit rests in how it showcases brands and technologies that have passed from the scene — steam locomotives, for example. Also a thing of the past is the family carriage. (The exhibit includes a catalog illustration of the Kimball Barouche and the old American Phaeton; both look springy and fragile.) Corsets aren’t what they used to be.

A certain temper of advertising language also seems to have vanished, but the exhibit recaptures it for the close reader — “vegetable pills,” “never-break corset clasps,” and the assurance of a “pectoral balsam for coughs and colds.”

Luckily, archivists are busy collecting material history that still has the potency to teach and to inspire modern businesspeople. HBS has an Advertising Ephemera Collection that includes more than 8,000 trade cards. (About 1,000 have been digitized so far.) The Bates Trade Card Collection has another 500, most from Boston and Cambridge businesses.

Baker Library Historical Collections also has an extensive collection of trade catalogs, most from the New England of 1870 to 1900. And there is the Baker Old Class Collection — books, pamphlets, manuals, and periodicals related to printing and promotion from the Gilded Age and after.

Taken together, such collections offer a treasure house of perspective on the origins of modern advertising.

“As far as we’re concerned,” said Riggle of the exhibit, “we have a hit.”