“A University is only as good as its faculty, and we want Harvard to be the best place on Earth to be a faculty member,” said Judith D. Singer, senior vice provost for faculty development and diversity. “We very much want to use these results to ensure that they feel this is an environment that fosters their best work, and understand how Harvard can improve the quality of life for our faculty.”

Photo by Suzanne Camarata Photography

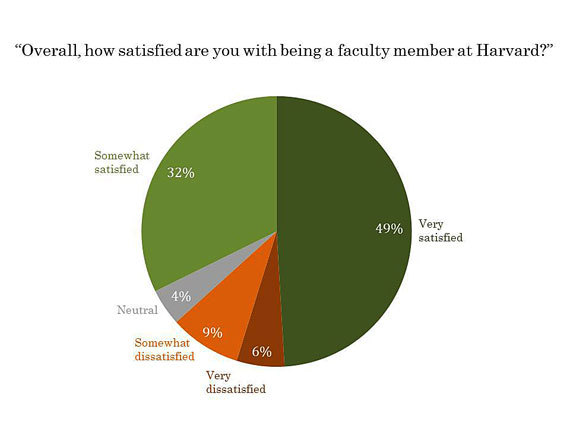

Survey finds faculty satisfaction rate at 81 percent

Quality of students and opportunities to innovate in their teaching top list

The vast majority of Harvard faculty report that they are satisfied with their positions here, according to the latest Faculty Climate Survey released today by the Office for Faculty Development and Diversity.

The survey, which was conducted during the 2012-13 academic year, examined attitudes toward a host of work-life issues, including job satisfaction, department atmosphere, mentoring, and stress factors. Seventy-two percent of faculty participated.

“A University is only as good as its faculty, and we want Harvard to be the best place on Earth to be a faculty member,” said Judith D. Singer, senior vice provost for faculty development and diversity and James Bryant Conant Professor of Education. “We very much want to use these results to ensure that they feel this is an environment that fosters their best work, and understand how Harvard can improve the quality of life for our faculty.”

Job satisfaction. Overall, 81 percent of faculty report being satisfied with their jobs, a rate that is comparable, and in some cases higher, than those of faculty at many peer institutions. Among the areas in which Harvard faculty report the highest levels of satisfaction are the quality of library content and services, the quality of students, opportunities to innovate in their teaching, and the quality of Harvard staff.

There was no area in which a majority of faculty members expressed dissatisfaction. Still, among their top complaints were time available for scholarly work, support for securing grants, funds available for conferences and travel, committee and administrative loads, and availability of teaching assistants.

Department and School atmosphere. The University has made strides in several areas since the last faculty climate survey in 2007. For example, significantly higher percentages of faculty now report that their department (or School) is a good fit (81 percent vs. 71 percent), that it creates a collegial environment (71 percent vs. 65 percent), and that it accommodates family responsibilities (70 percent vs. 64 percent). Men and women are equally likely to report that they have a voice in decision-making. However, tenured women and underrepresented minority faculty report more often that they have to work harder to be perceived as legitimate scholars, and that they are excluded from an informal network. They are also more likely to disagree that their department or School makes equal efforts to recruit women and minority faculty.

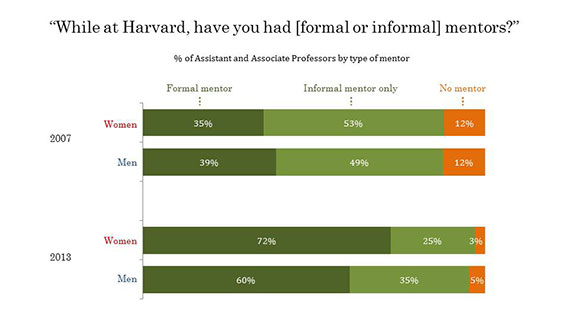

Mentoring. When the last faculty climate survey was conducted, half the assistant and associate professors had only an informal mentor, and 12 percent had no mentor at all. In response, many Harvard Schools instituted formal mentoring programs to help tenure-track faculty successfully navigate their careers. In the current survey, about two-thirds of the tenure-track faculty have a formal mentor and only 4 percent have no mentor at all. Equally important, satisfaction with the quality of mentoring has improved substantially, notably with no differences in satisfaction by gender.

“Clearly, there is still work to be done,” Singer said. “But we are heading in the right direction.”

Child care. Another issue revealed by the 2007 survey was insufficient options for high-quality, affordable child care. In response, the University renovated the child-care centers at Oxford Street and in Harvard Yard, increasing the number of on-campus slots available. Nearly half the faculty based in Cambridge and Allston who have children under 4 now use one of the Harvard-affiliated centers. A broad range of child-care programs have also been rolled out. Since its 2008 launch, the Ladder ACCESS program has provided nearly $5 million in child-care scholarships to ladder faculty, making it possible for faculty to afford high-quality care. The Dependent Care Fund makes it possible for faculty to bring dependents or child-care providers with them to conferences and on fieldwork trips. In 2012, the University launched the WATCH portal, an online hub that connects Harvard families who need help with Harvard community members who provide child care, pet sitting, tutoring, and odd jobs; it now has more than 2,000 active members.

“Faculty can’t do their best work if they are worrying about basic needs like child care,” Singer said. “We’ve spent the past few years coming up with a variety of solutions to help families, and increasing numbers of faculty are taking advantage of them.”

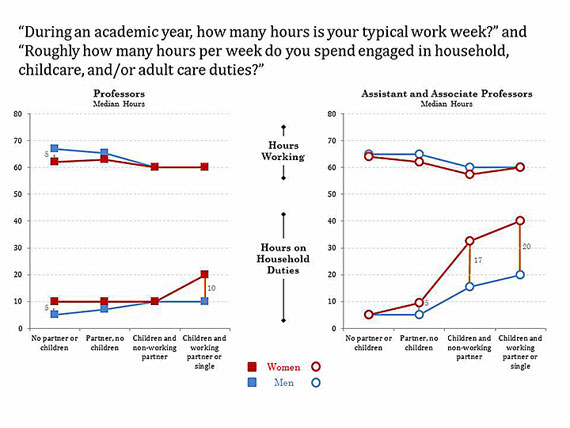

Some gender gaps remain. Despite progress toward gender equity, there remain many domains in which tenured women are the least satisfied and tenured men are the most satisfied, with tenure-track men and women falling in between. Women also report greater levels of personal stress than their male counterparts, particularly with issues like child care, care of an ill child, children’s schooling, and elder care. These differentials are not unique to Harvard, as similar patterns are found at peer Universities.

“The data shows not just that women feel the most stress, but probably that they are the ones responding to the crises with their children and their parents,” said Claudia Goldin, Henry Lee Professor of Economics, who studies women’s achievement, career, and families.

Although male and female faculty report working the same number of hours each week, women — especially those with children and either a working partner or no partner at all — report spending dramatically more time on household duties: 10 to 20 hours more per week. For example, these tenured women report spending a median of 20 hours a week on household responsibilities, in comparison to just 10 hours a week among tenured men in the same situation. This gender gap is twice as large among tenure-track faculty: women with children and either a working partner or no partner report spending a median of 40 hours a week on household responsibilities, while their male peers in the same situation report an average of just 20 hours a week.

Goldin attributed that gap to increases in the number of female faculty, and also increasing numbers of female faculty having children.

“This makes the work-life issue much more important at universities,” she said. “But it also reveals that more women believe they can handle both.”