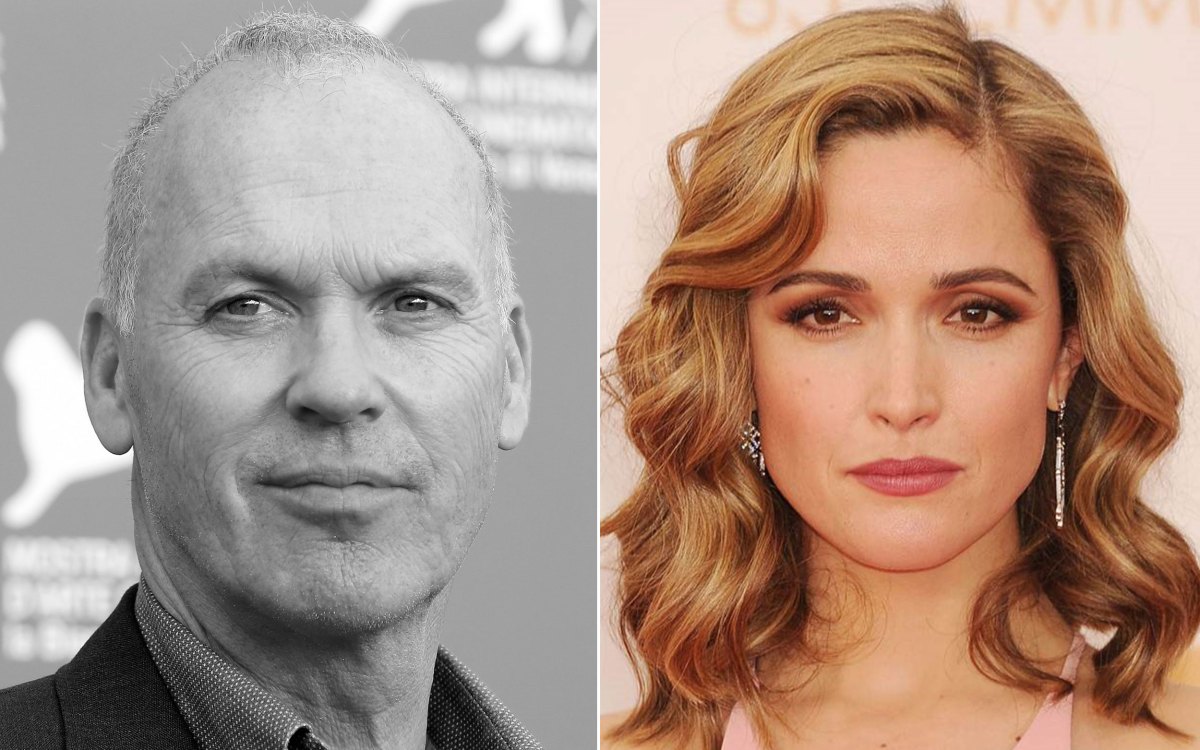

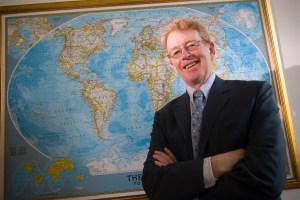

Bernardo Lemos (photo 1), assistant professor of environmental epigenetics, was one of four winners of the inaugural Star Family Challenge for Promising Scientific Research. “We want to fund research which would not otherwise be funded, research that would be new, and that would have large potential impact,” said Professor Douglas Melton (photo 2) during his opening remarks at the awards presentation (photo 3).

Photos by Juliette Lynch

Support on the cutting edge

Star Family Challenge awards back big ideas in science

“Jamie Star challenges and enables us to do something important, without being prescriptive about how it’s done,” Douglas Melton, the Xander University Professor and Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor in the Natural Sciences, said Tuesday about the Star Family Challenge for Promising Scientific Research.

At the inaugural awards ceremony for the challenge, Melton, who chairs the committee behind it, related an important dinner conversation with its founder, James A. Star ’83. Melton said the two discussed the need to fund interdisciplinary research, and the result was a clear target.

“We want to fund research which would not otherwise be funded, research that would be new, and that would have large potential impact,” Melton said. “This kind of research often happens when you look between fields.”

The challenge was established by Star and funded at his direction with a $10 million grant. Given biannually to Harvard faculty members, the awards range from $20,000 to $200,000 and are determined by a committee of senior FAS members.

At the ceremony in a packed University Hall, this year’s four winners presented research with jaw-dropping potential. Charles Lieber, the Mark Hyman Jr. Professor of Chemistry at the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), is researching ways to use nanoscale technology to create electronics that could be injected into the brain and become fully integrated with neural networks. The results could someday be used to treat diseases and traumatic injuries, Lieber said, citing epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease. Such “injectable electronics” would be much less invasive than surgery.

Lieber also described his “ultimate dream”: “injectable closed-loop systems for the detection, monitoring, and treatment of diseases.”

Richard Lee, a professor of stem cell and regenerative biology at Harvard University and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, said a simple question lay at the heart of his research: “Can DNA tell time?” He followed with another: “Why is it that a dog keeps track of time seven times longer than we humans do?” The mechanism by which DNA tracks time is “one of the great unsolved mysteries of science,” said Lee, and the answers could help fight disease.

Lee noted that people with muscular dystrophy die at about age 20, and those with cystic fibrosis die at about 30. “We’d like to extend this time,” he said. “Could we slow down time within the muscles of MD patients or within the lungs of CF patients?” He added in a later interview, “I am a physician, so thinking about patients with diseases is all that I do. I dream about being able to slow down diseases, or delay their onset.”

Conor Walsh, an assistant professor of mechanical and biomedical engineering at SEAS, is developing wearable technology — “soft wearable robots” that could someday help people with limited mobility walk with their normal gait. His interdisciplinary research combines robotics, engineering, and biomechanics.

Bernardo Lemos, assistant professor of environmental epigenetics at Harvard School of Public Health, studies the extraordinary resilience of microanimals called tardigrades. “These organisms can be boiled, frozen, desiccated, sent into space, subjected to radiation, and yet still remain alive,” Lemos said. His research has potential in biotechnology, materials science, and public health. “Those of us in public health worry about pollution, lead paint, heavy metals, and how all the toxicity they spread impacts us. Well, tardigrades are barely impacted at all by these things,” and knowing why could advance research, he said.

After hearing from the four winners — selected from more than 60 submissions — Star said, “These were phenomenal presentations. I’m so glad to be supporting such cutting-edge research.”

The challenge will continue to encourage submissions from both the natural and social sciences at Harvard, and work to help close the funding gap faced by researchers.