In 1914, poised for war

Many of the joyous students graduating a century ago would later be drawn into a rising world conflict, in which some of them would die

On the sunny Thursday of June 18, 1914, Harvard opened its gates (though not then to women) for a Commencement celebration that would launch an unusually large undergraduate class of 537 into the world.

Among those receiving diplomas that morning at Sanders Theatre were a future U.S. senator (Leverett Saltonstall, descended from a line of graduates dating back to 1642), a future bestselling novelist (Edward Streeter), and a future foreign policy adviser to President Franklin Roosevelt (Benjamin Sumner Welles).

Hope marked the day and the class. “A burst of song, a trumpet blast rings clear,” read a poem by Pitman Benjamin Potter 1914 on the penumbral page of the class album that year. “We close old records but to open new.”

The day before, Radcliffe College, celebrating its 20th year, held its own graduation ceremony at Sanders. In the Class of 1914, numbering 101, 17 seniors graduated magna cum laude, and five summa cum laude. According the “Book of the Class of 1914,” graduates had taken 1,199 courses and had written more than half of the articles in Radcliffe Magazine.

Those sweet Commencement days marked a last, soon-lost innocence for Harvard, for Radcliffe, and for students everywhere. The world was on the verge of the first global war, which killed 16 million people and lit the fuse on wars to follow. World War I began on Aug. 1.

Harvard, like the world around it, was swept into the conflict, even though America delayed its entry until the spring of 1917. By Nov. 11, 1918, 11,319 Harvard alumni, students, and faculty had served in the military, two-thirds of them as officers, while 373 died as the result of service, including 19 from the Class of 1914.

British citizen Clyde Fairbanks Maxwell 1914 left for England barely a month after graduation. He was killed in combat in 1916, and lies in an unmarked grave. William Barry Corbett 1914, a high school English teacher in Boston, joined in May 1917. He died charging a machine gun nest north of Verdun 11 days before the war ended.

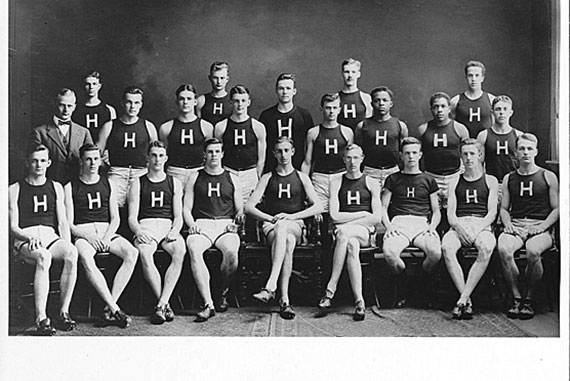

Others suffered prolonged deaths. Harvey Rexford Hitchcock Jr. 1914, a three-sport athlete and All-American tackle for the Crimson, saw combat in the summer of 1918 as an artilleryman in France. In 1920, he was admitted to McLean Hospital in Waverley, Mass. He died there in 1958. For the 1921 class report, Hitchcock listed his occupation as “Reflection.”

Three Radcliffe graduates died in the war too, all from disease and all nurses: one each from the classes of 1910 and 1911 and the third a special student from 1908 to 1913.

Four other young men died in service to Germany. Two of them received their Harvard degrees that day in 1914, one in divinity and the other in dental medicine.

In the traditional procession of graduates, old and new, that wended its way to Sever Quadrangle for Harvard Alumni Association festivities, records show, were 36 surviving graduates of the Class of 1864, whose 99 graduates included Robert Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s eldest son. The Civil War-era classmates had earlier gathered at Phillips Brooks House to celebrate their 50th class anniversary. Thirty-five of their number had fought for the Union, and six for the Confederacy.

An air of innocence had held sway over all four years of study for the classes of 1914 at both Radcliffe and Harvard. “Seldom has fortune deserted the Class of 1914,” read the first few words in the freshman yearbook. The official class dinner at the Student Union (now the Barker Center) was “the great event of the year,” wrote Robert Treat Paine Storer 1914 in the history (despite Henry James getting an honorary degree that spring).

Glimpsing a century back

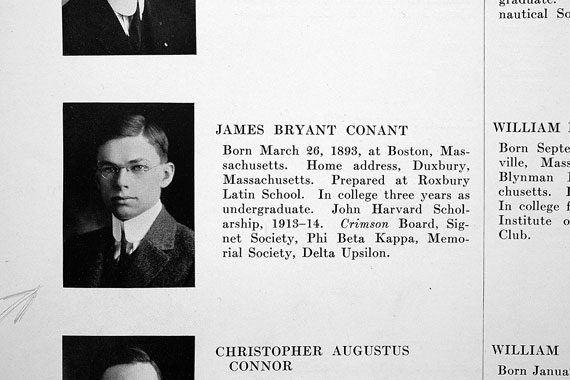

Future Harvard President James Bryant Conant, pictured here in the Harvard Class Album of 1914, was among the most celebrated members of the class, although he actually finished his A.B. by 1913. Photo courtesy of Harvard University Archives

One view of a typical undergraduate room, circa 1910. Electric lights were installed in Harvard Yard during the Class of 1914 era. Photo courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Harvard’s varsity track team, spring 1912. By 1914, the squad’s one-mile relay team held the world’s record. Photo courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Two Radcliffe College students mug for the camera during a 1914 tennis outing at Silver Bay, Lake George, N.Y. Photo courtesy of Schlesinger Library

A few members of the Radcliffe College Class of 1914 gather for an informal portrait. Photo courtesy of Schlesinger Library

The atmosphere at Harvard College then had drawn a warning from incoming President A. Lawrence Lowell in 1909 about a “painful defect” in higher education at large. “No one will deny,” he said in his inaugural address, “that in our colleges high scholarship is little admired now.” No blame went to the star-studded Harvard faculty of that era. Josiah Royce taught philosophy; so did George Santayana. Celebrated Shakespeare scholar George Lyman Kittredge dazzled during lectures. Frederick Jackson Turner, with his culture-shifting notions of how the frontier shaped America, taught history.

Brilliance simmered too amid the undergraduates of that era. James Bryant Conant, a future Harvard president, started with the Class of 1914, but graduated in 1913. John P. Marquand 1915 went on to write “The Late George Apley.” John Dos Passos 1916 became a famous novelist too.

The yearbook histories for the Class of 1914 to some extent celebrate the lightness and frivolity Lowell had decried. The history of the sophomore year noted football, “smokers” (official class parties), track, baseball, and a new subway, “that subsoil marvel.” The junior yearbook recorded more smokers, victories in crew and track, and the move into Harvard Yard dormitories, where electric light had just been installed.

The history for senior year identified the class clowns (James Ripley Osgood Perkins and Albert Franklin Pickernell). It also mentioned football rallies, “movies,” multiple victories over Yale, more smokers, and in March a “long-to-be-remembered” Hot Dog Night.

At Radcliffe, the Class of 1914 celebrated its glee and mandolin clubs in print, along with dozens of drama productions (with 151 parts played in four years, records show). Its class history, outlined in the Radcliffe Fortnightly of June 17 (price: 5 cents) noted a party the class threw for new freshmen in 1912. That featured a visit by three “grand-opera stars.” Later that fall, a house party featured the equivalent of ghost stories, with two classmates “describing the horrors of the working girl.”

The class book of 1914 also noted a streak of athletic prowess: basketball championships in 1912 and 1913, and strong teams in field hockey, lacrosse, tennis, and swimming.

The Radcliffe class was proud of the crocuses it had planted outside the gymnasium, and the class color, yellow, which the flowers represented. (In the class book, graduates bragged they had “put the yell in yellow.”) The book also listed 14 class “innovations” since 1910. One established a freshman class photo, and others included a class supper and class pins.

The Radcliffe yearbook included an innocent rhyme unknowing of the difficulties to come: “So give three cheers, and one cheer more, for the glorious class of 1-9-1-4.”