Calming the working mind

From meditation to yoga, Harvard finds new paths to wellness

Marianne Bergonzi first tried yoga when she was 50 years old. Describing the experience as life-changing, Bergonzi soon began teaching classes. “I knew I had to pass the yogic philosophy on to people who [may] never get a chance to learn the body, mind, and breath connection.”

Jeff Matrician, an acupuncturist at Harvard University Health Services’ David S. Rosenthal, M.D. Center for Wellness, treats patients for reasons that include pain management, neurological conditions, asthma, drug abuse, alcoholism, weight control, smoking, stroke, gastrointestinal disorders, gynecological and obstetric problems, and stress management.

The Western approach reduces symptoms to determine causes for problems in the body, Matrician said. Eastern medicine differentiates itself with a global or holistic approach. “Perhaps a problem is that we’re looking for specific causes to treat, rather than approaching with a larger view,” Matrician said.

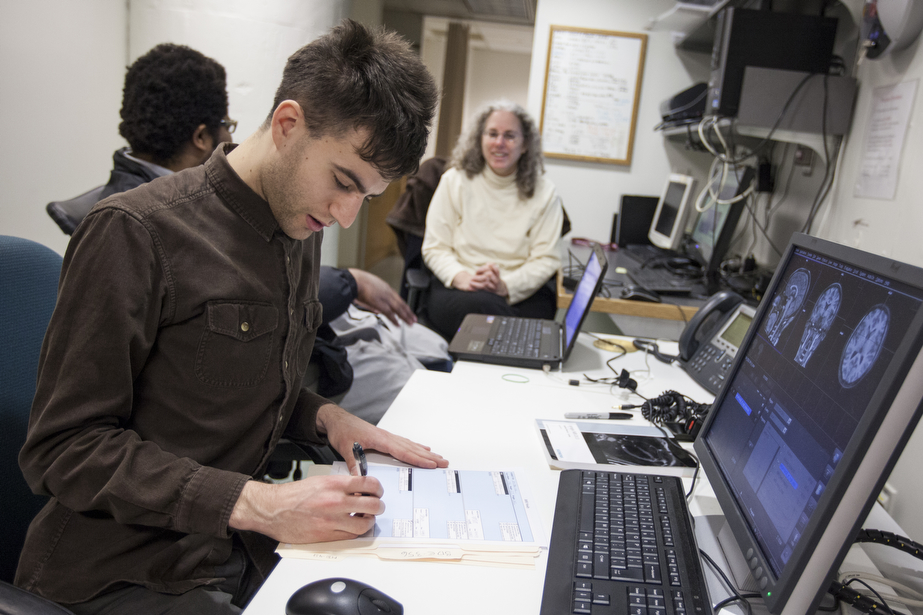

Harvard-affiliated researcher Sara Lazar has led a series of studies to help understand what kind of structural and functional changes occur in the brain with meditation. Noticing profound, positive changes after starting yoga in graduate school at Harvard, she decided to shift her career to try to understand them.

Lazar said meditation became a topic of interest within the medical community in the 1960s and ’70s, but faced setbacks as its associations with the generational drug culture undermined its practical benefits. Furthermore, the language used to describe meditative practices was often mystical, damaging its credibility, making claims while failing to align with the scientific method.

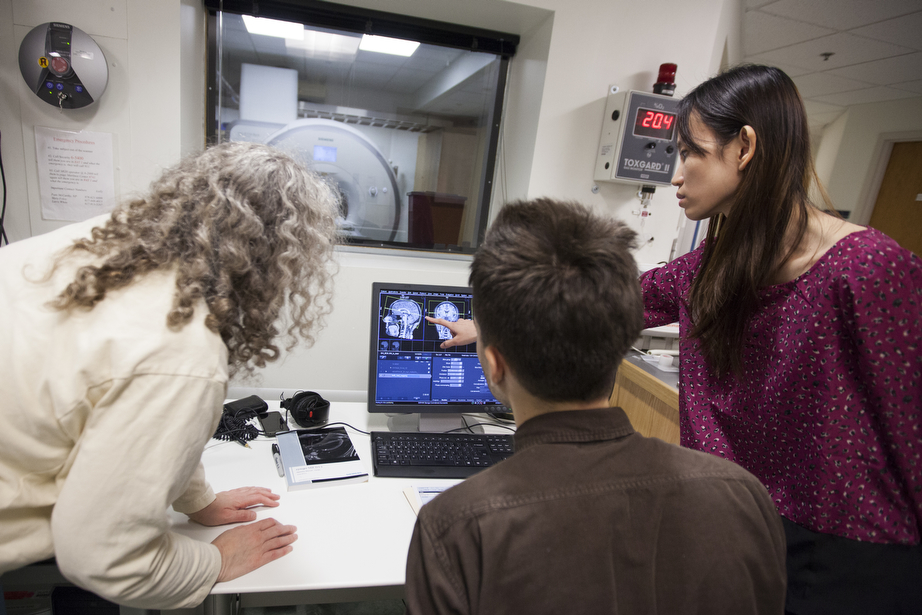

Lazar and her team were able to utilize a secular meditation-based clinical program that had been created to reduce stress and medical symptoms. Subjects in the six-month blind study are given MRI scans before, two months after, and four months after completion of a two-month stress-reduction program. The MRIs first scan the brain structure, then observe resting brain activity.

The recent study is built on previous ones that have shown that meditation increases hippocampus gray matter, decreases amygdala gray matter, and may slow age-related decline of the prefrontal cortex. These results provide compelling neurobiological reasons why meditators report less stress; a reduction in symptoms associated with depression, anxiety, pain, and insomnia; enhanced focus; and an increase in general life satisfaction.

Lazar said she is not trying to demystify anything spiritual through these studies. She admits that the study’s meditation practices contain “underpinnings of Buddhist philosophy,” but prefers to view meditation with a “practical approach, understanding [it] in terms of brain structure.”