Ties to the past

Six cravats of Walter Gropius reflect the famed modernist architect and his love of joy

We all know how hard it is to get your hands around the past. So why not put the past around your neck?

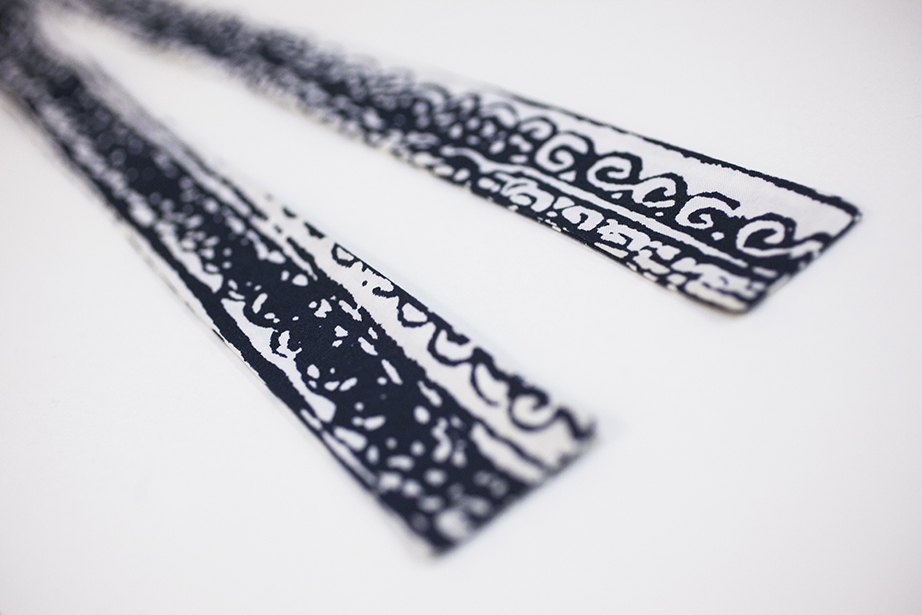

That’s possible in theory in the case of six bow ties once worn by the celebrated architect Walter Gropius (1883-1969). The half-dozen slender cravats are housed in a segmented archival box at the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Frances Loeb Library. “It was the architecture gear of a certain era,” said Benjamin Prosky, GSD’s assistant dean for communications (and a tie-free, open-shirt kind of guy).

Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus school and a visionary with nonconformist views, fled his native Germany in 1934 after receiving threats when the Nazis took control. Following a sojourn in London, he began teaching at Harvard in 1937.

Photographs show that he favored bow ties, in earth tones or daringly bright prints. This sartorial habit was less Gropius’ personal taste and more a fixture of the era in which he lived. Men wore hats, suit jackets, and ties, often of the bow variety.

“These brilliant little butterflies were Grope’s only vanity,” wrote his wife Ise in 1969, using his nickname in a note written a few months after he died. She had written to Gropius friend and collaborator Chester Nagel, and gave him the six ties for Christmas that year, “as a small token,” she wrote, “of the friendship that united the two of you.”

The ties indicate that Gropius preferred natural materials (in this case, cotton) and straight bow ties rather than varieties with ends that resemble “bat wings” or “thistles,” and that he liked ties with a dash of color. Perhaps that last illustrates the architect’s desire “to make beauty a basic requirement of life,” as Nagel wrote in an essay on Gropius, “to make of living a joy.”

Bow ties today, in a cinematic context, denote the well-turned rake, the professor, or sometimes the skinny-necked nerd. In an earlier age, they signified the architect, the professor (again), the well-educated man with a streak of rebellion, or the well-dressed archconservative.

But bow ties, first worn by 17th-century Croatian mercenaries, had martial origins. Appropriate for Gropius: This man of peace and collaboration was also a four-year combat veteran of World War I who won the Iron Cross (“when it still meant something,” he confided to Nagel). Gropius escaped death many times, once fleeing machinegun fire on horseback, but not before taking bullets through a shoe heel, a coat pocket, and his hat.

Gropius went on to help make architecture modern, to become an influential educator, and to define design in terms of joy. “It brings inert materials to life by relating them to the human being,” he said of architecture. “Thus conceived, its creation is an act of love.”

In a final written testament before his death, he repeated only one sentiment twice: “Love is of the essence.” Gropius also left this final wish: “Wear no signs of mourning.”