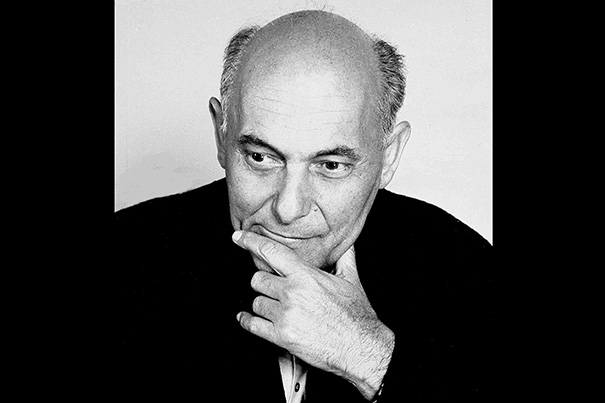

“I do not use my old scores with the markings in them,” wrote maestro Sir Georg Solti (photo 1). “I do not want to be influenced by my old way of thinking about a work; I want my approach to be as fresh as possible.” Solti studying at his retreat on Italy’s west coast near Castiglione della Pescaia (photo 2). The graphite sticks he used throughout his scores (photo 3).

Credits: Photo by Allan Warren, photos courtesy of the Solti family and the Weissman Preservation Center/Harvard University

Before the baton, a red pencil

Solti’s creative process in detail, via digital exhibit

In addition to his extraordinary gifts as a maestro, Sir Georg Solti had a knack for concise self-analysis. “I was born and trained to communicate music,” he wrote in his memoir.

Harvard curators, librarians, and conservators are honoring that conviction with an online exhibit based on annotated conducting scores that were donated by the Solti family to the University’s Eda Kuhn Loeb Music Library in 2011.

Solti (1912-1997) was a giant of 20th-century music whose decades-long affiliation with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra included 22 years as its director. By combining pages from his scores with audio clips, the digital collection illuminates the interpretive choices of an intense close reader and problem solver.

“The first time I saw one I thought someone had been scribbling on it,” said Valerie Pitts, Lady Solti, Sir Georg’s wife, in an interview included in the exhibit. “Later on, he adopted red pencil, when he was older, because he didn’t wear spectacles when he was conducting, which was not vanity at all, it was a practicality that he sweated a lot. And he said, ‘If I wear specs they’ll fall down my nose or they’ll mist up.’”

She added, “Therefore, the red pencils were very important for aging eyesight because these he could see.”

Though not part of the digital exhibit, scores of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony from 1961 and 1984, used in Professor Richard Beaudoin’s music theory class, illustrate the material’s potential as a teaching tool, noted recordings librarian Robert Dennis. They also demonstrate the conductor’s openness to change.

“I do not use my old scores with the markings in them,” Solti wrote. “I do not want to be influenced by my old way of thinking about a work; I want my approach to be as fresh as possible.”

Among the digitized materials is Solti’s markup of the second movement of “Concerto for Orchestra” by his teacher, Béla Bartók. Solti rigorously followed Bartók’s metronome marks, but grew confused when one did not seem to fit the piece. After checking the original manuscript, he realized the mark was a printer’s error that had been republished for 50 years.

(On a lighter note, and of particular interest to football fans, are Solti’s annotations for “Bear Down, Chicago Bears,” which he led for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at the conclusion of a Tchaikovsky-Liszt concert three days before the Bears defeated the Patriots in Super Bowl XX.)

“We are seeing a steady stream of interest in working with these materials, which will likely increase as the presence of the archive at Harvard becomes more widely known through this online exhibit,” said Sarah Adams, the Richard F. French Librarian. “Several of our faculty members now regularly incorporate in-depth study of particular scores into their teaching and their students turn to the scores for their own projects.”

One such student was Matthew Aucoin ’12, who consulted Solti’s scores to prepare for his Harvard production of Mozart’s “Nozze di Figaro.” Aucoin went on to win the Georg Solti Conducting Apprenticeship with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and made his conducting debut there last month.

Aucoin is not alone — musicians and scholars from as far away as the Georg Solti Accademia in Italy and the Hungarian State Opera have sought to use the archive.

About 20 scores are highlighted in the digital exhibit. The rest are available for research and teaching at the Loeb, whose staff is in the process of seeking permissions to digitize and make available the full collection through the library’s digital scores and libretti site.

“The exhibit offers a refined, informed glimpse into the collection,” said site developer Enrique Diaz.

Its title, “Music, First and Last,” follows that of the last chapter in Solti’s memoir, where he wrote, “A conductor must be a teacher, first and foremost.” The digitized scores are not only educational, but also the realization of the maestro’s dream that his scores be shared with musicians worldwide.

“The exhibit offers a first glimpse of the wealth of musical and intellectual insights that Solti’s scores can provide for performers and scholars,” said digital program librarian Kerry Masteller, who worked closely with Dennis to research and organize it. “It is in keeping with Solti’s hope that his collection would find its home at an institution that deeply valued both music and education.”