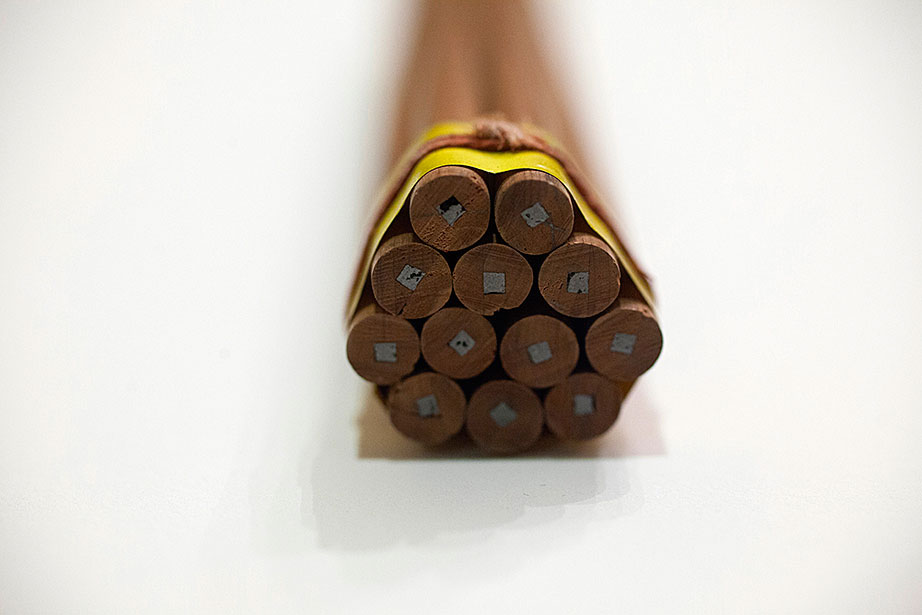

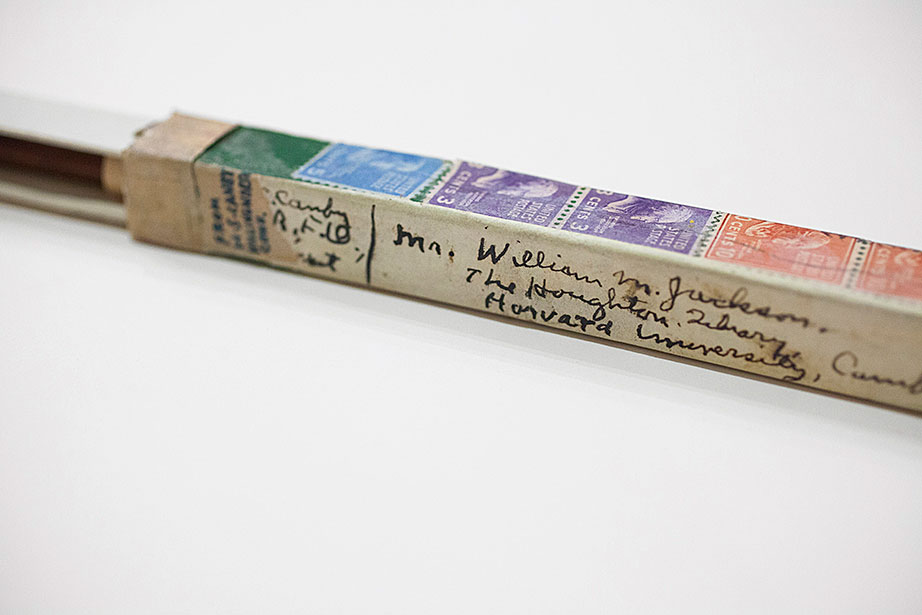

The first installation of Curio features famous writers’ implements found in the collections of Harvard University. Graphite pencil owned by American poet e.e. cummings is pictured at Houghton Library. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The things they carried

At Houghton, artifacts from the writing life

We get close to long-dead great writers by reading the works they left behind. But there is another way, which can be just as electric and emotional: to see or touch or just be near artifacts from their writing lives.

Harvard’s Houghton Library makes such proximal resonance possible. Objects from the lives of literary greats, the things that might have lain on their desktops, are housed in the Z Closet Collection and in other places set aside for material oddities that can’t be cataloged in the usual way. Librarians call such objects “realia” and store them in custom boxes.

“We’re good with books and manuscripts, but objects present special challenges,” said Peter Accardo, Houghton’s coordinator of programs. “They demand material expertise and care.”

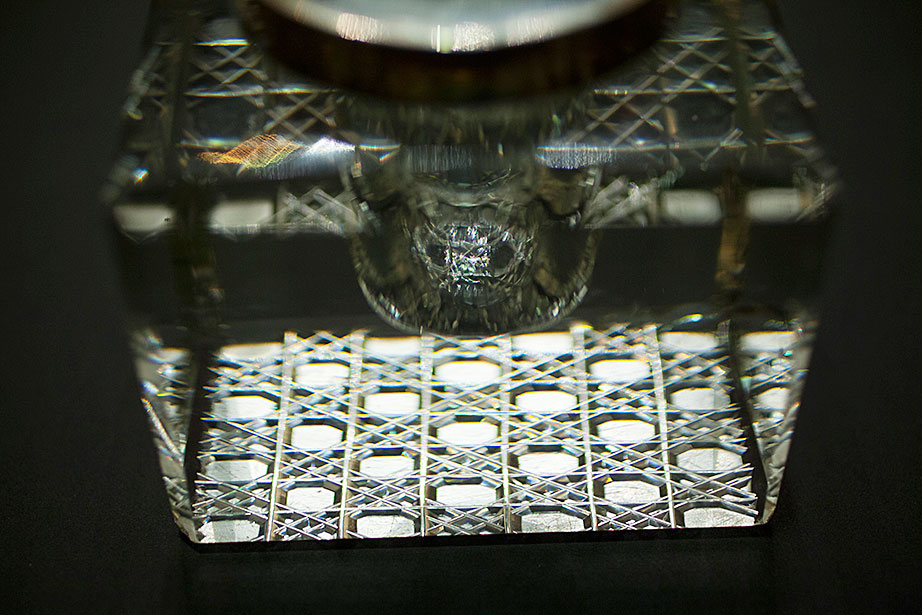

John Ruskin’s magnifying glass — a gift from Harvard’s Charles Eliot Norton, an executor of Ruskin’s estate — is still kept in a century-old box from Boston jeweler Rand & Crane. But housing that old box is a new one, made of acid-resistant paperboard. A similar modern box is where Houghton keeps a pencil owned by E.E. Cummings. It’s tied inside with a cream-colored ribbon.

Many such objects at Houghton arrived with more conventional literary materials, like books and letters, but were accepted despite having no direct utility for a literary scholar. Said Accardo: “You can’t very well tell a donor, ‘The library is not interested in T.S. Eliot’s Panama hat or Charles Dickens’ walking stick.’ ”

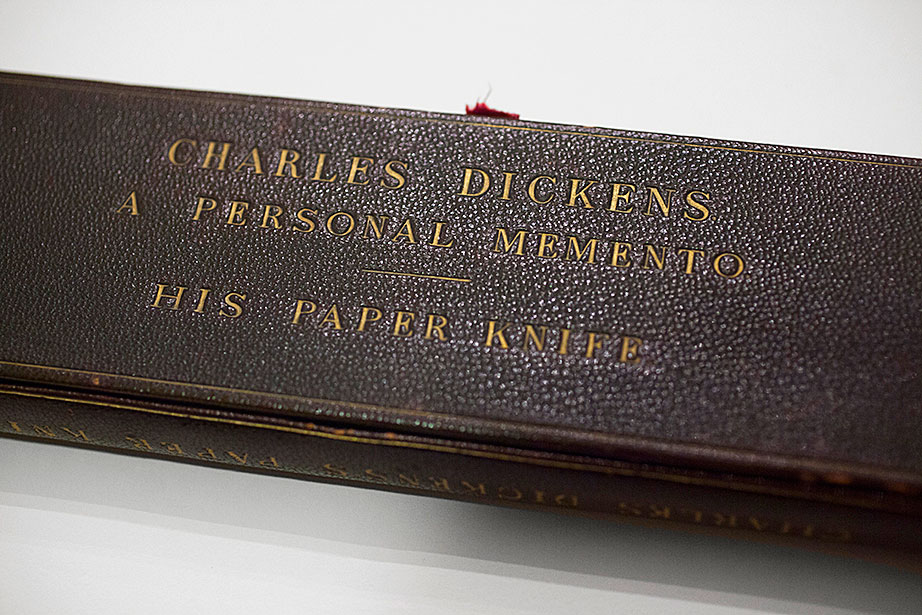

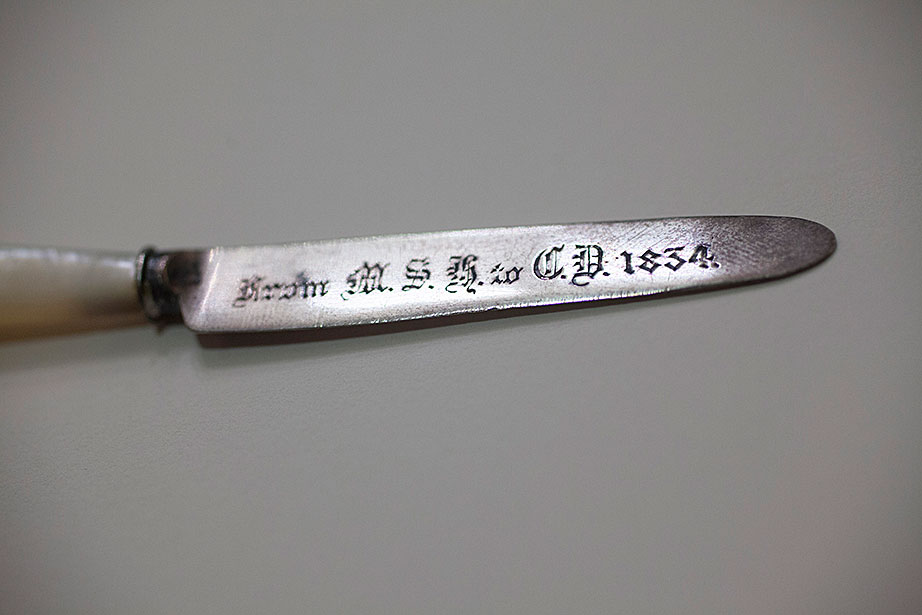

The materials occasionally include fakes, such as the pair of flintlock pistols supposedly owned by George Washington. (They turned out to be inauthentic.) “There’s great traffic involved in objects from literary and historic figures,” Accardo said. But most of Houghton’s artifacts come with proof of origin. An ivory letter opener belonging to Dickens, for instance, is stored with a two-page note from Georgina Hogarth, the author’s sister-in-law and housekeeper.

Nearby, propped in a wooden box, is the tiny brass seal Dickens used for letters. It was the size of a thumbprint, and fixed to a dark wooden handle. Accardo peered at it, and then stood up straight. “This is the kind of thing I love,” he said.