Howard Gardner, the Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education, recently reflected on his influences. “We are the sum of whoever we worked with,” he said.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Howard Gardner: ‘A Blessing of Influences’

Wide-ranging scholar praises counsel from others of similar breadth

We all owe our lives to someone, starting with mother and father and then outward along a spreading tree of life going back in time.

For those who make a living in the academic realm, a second tree of life is entwined with the first: a branching series of mentors and intellectual influences. “We are the sum of whoever we worked with,” said developmental psychologist Howard Gardner, a celebrated, wide-ranging scholar based at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE).

For him, that sum includes a few names everyone knows. Erik Erikson and David Riesman were both at Harvard when Gardner was an undergraduate. Jean Piaget and Claude Levi-Strauss corresponded with the young scholar before he earned his Harvard Ph.D. in 1971. (The two men were soon the subjects of his first trade book.) In 1970, by chance, each of these iconic revolutionaries in the realm of ideas — one a theorist of cognition and the other an anthropologist — wrote letters to Gardner on the same day, April 10.

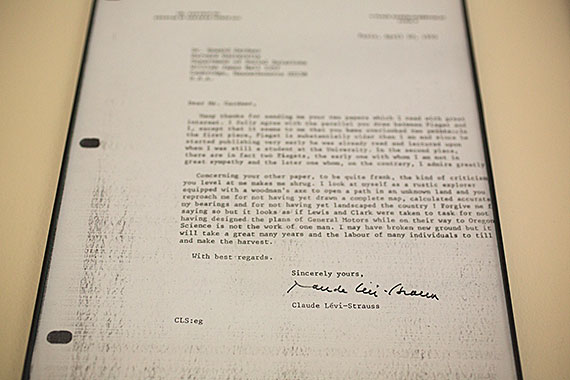

The Levi-Strauss letter, in response to Gardner’s first journal article, is framed in his Longfellow Hall office. It expresses general agreement with the young scholar, but also delivers the kind of stings that academics sometimes inflict on one another. “To be quite frank,” the letter reads in part, “the kind of criticism you level at me makes me shrug.” (The men went on to become friends and frequent correspondents.)

Wall of fame

Gardner, who himself is now a longtime important influence on two generations of students, keeps an office in Longfellow Hall.

In lieu of diplomas and awards, Gardner lines his office walls with memorable letters and other reminders of his mentors and academic friends.

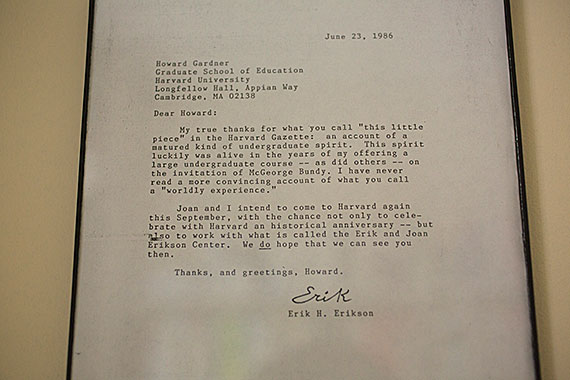

One framed letter is from Erik Erikson, a legendary developmental psychologist who was Gardner’s tutor at Harvard College.

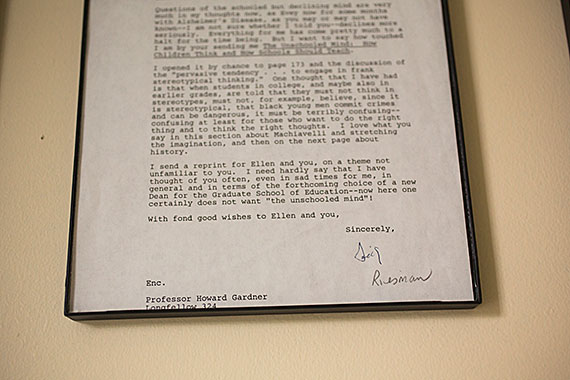

Another framed letter is from celebrated sociologist David Riesman, author of “The Lonely Crowd” and an important Harvard influence.

A letter from anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, who corresponded (and argued) with Gardner for decades.

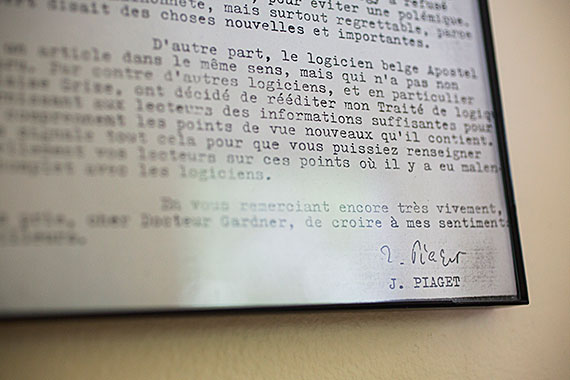

An early letter from Jean Piaget, whom Gardner credits as intellectually “the single biggest influence in my life.”

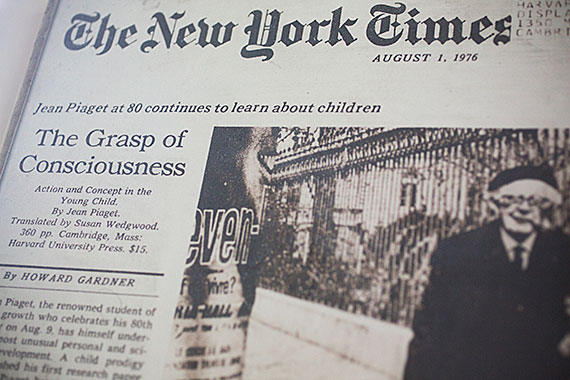

Gardner framed a copy of his 1976 review of a book by Piaget, whose picture captures the older scholar’s Gallic charm.

“Two of the most distinguished people in the world wrote back to me,” said Gardner, amazement still in his voice, along with admiration for an example of generosity he still follows. “I answer every letter I get, as long as it’s not designed to irritate. That’s how I pay these people back, by responding.”

In a typical day, that might mean writing a half dozen letters, along with emails — a time-eater of enormous proportions, he said.

Gardner keeps old letters and similar artifacts on his office walls partly for the students who come in and out. “It gives them a sense of lineage and continuity,” he said. “I’m very historically minded.”

Not everything in Gardner’s office has such apparent import. Decorations include a toy VW (yellow), a carving of an outrigger canoe, five labeled chairs (one says “High Priority”), a candy dish decorated with sea horses, an alarm clock, and a quill pen. The last two items, perhaps, underscore Gardner’s still-fervent scholar’s life after 52 years at Harvard. The clock is still ticking on what is left to do (he turned 70 in July), and much of that involves writing.

The prolific Gardner, officially the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education, is the author of more than 20 books. His latest, released in late September, is “The App Generation,” co-written with young University of Washington digital media scholar Katie Davis, Ed.D. ’11. She considers Gardner a mentor, and he agrees. Such relationships “are always dualistic,” Gardner said of such mutual intellectual attractions. “It’s seeing facets of oneself in the other person.”

Such relationships have enriched his life for decades. “Howard,” he remembered a friend saying, “you have a talent for attracting mentors.” Their number and variety is evident in “Howard Gardner Under Fire” (2006), a book of essays critiquing his work. (“It was undertaken with my blessing,” he said of the volume, which includes responses to each of his critics.) It opens with “A Blessing of Influences,” an essay on those who positively impacted his life. It is 30 pages long.

Pressed for time, Gardner supplied the highpoints of his mentored life, beginning with the comfort of his upbringing in Scranton, Pa. His Jewish parents — sensitive and cultured, though without university educations — had fled Nazi Germany in 1938. Around them gathered like-minded exiles in that Pennsylvania coal-mining town, an early simulacrum of the largely Jewish and European scholars who would later influence Gardner’s flowering life of the mind.

“Intellectually,” he said of one of them, “Piaget was probably the single biggest influence in my life.” He came to know the burly Swiss psychologist and philosopher, even though Gardner’s French was as limited as Piaget’s halting English. (In person, they used an interpreter.) In his office, Gardner has a framed blowup of a 1975 review of a Piaget book he wrote for The New York Times. Until the elder psychologist’s death in 1980, it was a sign of his influence, Gardner said, that he spent decades trying to prove Piaget wrong.

In personal terms, other mentors came into Gardner’s life earlier and more directly, starting at Harvard College in the fall of 1961. Erikson, a polymathic explorer of ideas and inventor of the term “identity crisis,” taught in what was then the Social Relations concentration. (Gardner still laments the passing of this short-lived amalgam of psychology, sociology, and anthropology.) “He was intellectually charismatic,” said Gardner of his junior- and senior-year tutor.

Blond, blue eyed, and Viking-tall, Erikson was “the most arresting figure on campus,” Gardner said, remembering his straight-backed stride. In those days, swimmers at Harvard’s Indoor Athletic Building did their laps without wearing bathing suits. “Even naked,” a friend told Gardner back then, “Erikson looks 10 percent more distinguished than anyone else.”

Erikson also established what became an accidental type for the men who influenced his early academic path, said Gardner. (And they were only men, he said apologetically. “Fifty years ago, there were very few women in the academy.” But he credited American philosopher Susanne Langer for her later inspiration on symbol systems. One of her letters is on Gardner’s office wall too.)

The men who influenced him early on were not only largely Jewish and of European origin, they were intellectuals who took a lot of interdisciplinary turns in their own young lives. “Many of my mentors had unusual paths,” said Gardner, who to this day espouses the richness of seeing a problem through the lens of many disciplines.

Erikson never went to college; was a painter who held that “an artist is a person of some talent with no place to go”; and taught in a primary school in Vienna run by Anna Freud, daughter of Sigmund Freud. It was an unusual occupation for a man, but a formative one for a scholar who would spend his life investigating psychological development in children.

Once in the United States, Erikson attracted patrons, despite his lack of academic credentials. “He must have been brilliant and vulnerable,” said Gardner of his Harvard mentor. “People wanted to help him. This is an incredibly unusual trait, which I don’t have.”

Riesman was also at Harvard during Gardner’s undergraduate years. He was another restless polymath, who in this case turned from a brilliant law career to sociology, in which he had no formal training. His co-authored 1950 study of postwar American conformity, “The Lonely Crowd,” remains a classic.

Riesman postulated that in the 19th century most people were inner-directed, with a focus on independence and self-exploration. After two World Wars, however, he held that Americans had become more “other-directed,” and that social rewards followed from conformity and not independence. In Gardner’s latest book, he and co-author Davis suggest a new generation that is “app-directed” — citizens of a digital world that may encourage superficial relationships and stifle creativity. The work draws on sociology from Riesman and psychology from Erikson, said Gardner, and brings the ideas of his old mentors into the 21st century. “My intellectual lineage endures today,” he said. “I’m still using their ideas for what I do.”

In the summer of 1965, as a new graduate of Harvard College, Gardner met Jerome Bruner, “the most famous psychologist of the ’60s and ’70s,” he said, and a pioneer of cognitive psychology, which studies how people actually think, remember, and learn. Bruner also had a deep interest in how children learn, setting off in the young Gardner a lifelong interest in pre-collegiate education.

More than that, Bruner ran his research groups in a nonconfrontational, collaborative way that Gardner took to heart in his own life. “He is the person who has had the most influence both on what I do, and how I do it,” he said. Like Gardner’s other mentors, Bruner used more than one discipline as a lens for learning. At age 70, he started teaching at the New York University School of Law — and still does, at age 98.

Gardner is a polymath in his own right. He spent 20 years after earning his Ph.D. studying neurology, from the point of view of both brain-damaged adults and gifted children. “I’m not a physician,” said Gardner, but “I used to joke: I’m a neurologist from the neck up.”

In that realm came another mentor, Norman Geschwind, a Harvard-trained physician who pioneered behavioral neurology, the study of how the architecture of the brain directs thoughts and behaviors. When that architecture is altered (Geschwind was an expert on brain lesions), conditions like aphasia can result. Gardner spent a lot of formative time in a series of Boston aphasia clinics. He said of himself and Antonio Damasio, the noted behavioral neurologist, “We think of ourselves as being children of Norman.”

Geschwind is the author of another letter on Gardner’s office wall, one that was part of their dialogue on where visual, auditory, and spatial perception reside in the human brain. His late friend helped establish the links between brain and mind, in part by taking another step that Gardner admires: acknowledging the past. Geschwind rediscovered the work of 19th century German and French proto-neurologists. “This whole source of knowledge was forgotten,” said Gardner, lost in the United States because of enmities stirred up during the World Wars.

The last of Gardner’s main early influences was not a public intellectual in the way Piaget, Erikson, or Riesman were. Still, Nelson Goodman “was already one of the most esteemed philosophers in the English-speaking world,” Gardner wrote recently in a personal history of Harvard’s Project Zero.

Gardner was a second-semester graduate student at Harvard in 1967 when he joined Goodman in founding the project, an HGSE research group intended to study how children, adults, and organizations learn. Gardner’s recently authored history was “bus writing,” he said — that is, something to have in place in case he got hit by a bus.

As a philosopher, Goodman was interested in the nature of knowledge. He was also a student of the arts, was married to a painter, once managed a Boston art gallery, and so was drawn to founding Project Zero as a way of investigating artistic knowledge and creativity. These were interests that became central to Gardner’s own work. “Nelson had a lot of intellectual influence on me,” he said.

Goodman ’28 also had classical ideas about clarity, and would say that he stopped reading something when it no longer made sense. Gardner took Goodman’s lesson to heart: “I’m a demon for clear writing, in myself and others,” he said.

So many influences, and so much work still to do. Gardner jokes that despite all the turns his work has taken and all the disciplines it has tapped for insight, the short version of his obituary will still likely say, “Father of multiple intelligences.” His groundbreaking “Frames of Mind” appeared in 1983, and Gardner fanned the flames of the discussion for years, though he has since “moved on,” he said.

As for actually moving on, as in retiring: Gardner considered it five years ago, when he turned 65. But his family rose up “vociferously” against the idea, he said.

“At a certain point I will kick myself out,” added Gardner. “Unless I kick the bucket first.”

One of an occasional story on senior Harvard faculty members who recall the mentoring influences that helped to shape their academic lives.