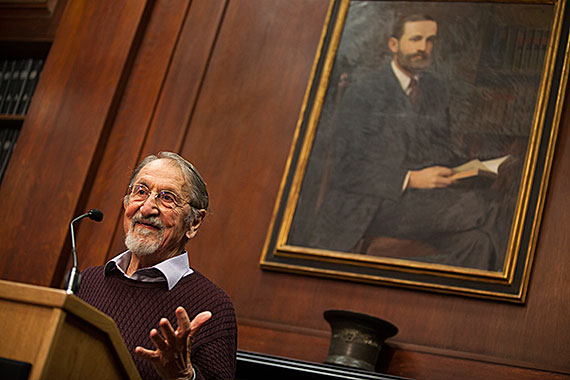

Harvard Professor Emeritus Martin Karplus is one of three winners of this year’s Nobel Prize in chemistry. He is pictured at home in Cambridge, Mass., moments after hearing the news.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard professor wins Nobel in chemistry

Martin Karplus is one of three to share in prize ‘for the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems’

Martin Karplus, the Theodore William Richards Professor of Chemistry Emeritus at Harvard, is one of three winners of the 2013 Nobel Prize in chemistry, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced Wednesday morning.

The 83-year-old Vienna-born theoretical chemist, who is also affiliated with the Université de Strasbourg in France, is a 1951 graduate of Harvard College and earned his Ph.D. in 1953 at the California Institute of Technology. While there, he worked with two-time Nobel laureate Linus Pauling, who was an important early influence.

He shared the Nobel with researchers Michael Levitt of Stanford University and Arieh Warshel of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Warshel was once a postdoctoral student of Karplus, who worked with both men during six months in Israel during the 1960s. All three were then at the Weizmann Institute of Science with chemist Shneior Lifson, but have not worked formally together since that time.

The Nobel website said the prize was awarded for the researchers’ work in “the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems.”

With Karplus’ award, 47 current and former Harvard faculty members have received Nobels for wide-ranging work, including the tissue culture breakthrough that led to creation of the polio vaccine, negotiations that led to an armistice in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the first description of the structure of DNA, pioneering procedures for organ transplants, the development of gross national product as a measure of economic change, poetry, and much more.

The last before this was in 2012. Alvin E. Roth, a Harvard economist whose practical applications of mathematical theories have transformed markets ranging from public school assignments to kidney donations to medical resident job placements, won the economics prize.

Before dawn, in a downstairs hallway at his Irving Street house in Cambridge, Karplus already was turned out neatly in a dress shirt and dark pants, his only concession to the early hour being a pair of brown leather slippers.

He fielded calls from American, European, and Latin American news outlets. One interview was in French and another in German, languages he speaks fluently. He needed a translator for several calls in Spanish from Colombia. “It’s been one call after another,” he said.

“And hundreds of emails,” added his wife, Marci.

Most reporters calling the professor got an added soundtrack: occasional barks from the family dog, a 2-year-old cockapoo named Bib.

“I was sound asleep,” Karplus said of his 5:30 awakening at his home, which is on a shady street five minutes from Harvard Yard. Usually, he said, “you only get calls at 5 o’clock in the morning when it’s bad news.”

Breakfast was blue cheese on toast, with bacon, coffee, and orange juice. With him was Marci, who is his lab administrator at Harvard, and his son, Mischa, who works for a human rights nonprofit. (Two older daughters, both physicians, live out of town, one in Portland, Ore., and one in Jerusalem.) The phone kept ringing, and the message from Marci was always: Call back in 10 minutes, please.

“It’s clear,” she said later, “this is not going to slow down.”

While in his living room for an early interview, Karplus said that most of the phoning reporters repeated at least two questions: What was it like to get the Nobel Prize call? (“It was nice to hear,” he said. “I’ve known I was nominated for quite a few years.”) And they asked him to explain his work “in simple terms,” said Karplus, who studies the structure and dynamics of molecules. (“If you like to know how a machine works, you take it apart,” he said. “We do that for molecules.”)

The Karplus lab website at Harvard describes his research as “directed toward understanding the electronic structure, geometry, and dynamics of molecules of chemical and biological interest.” In use are, among other things, “semi-empirical quantum mechanics, theoretical and computational statistical mechanics, classical and quantum dynamics.”

Harvard President Drew Faust released a written statement saying, “We are very proud to celebrate Martin Karplus’ groundbreaking research today. Professor Karplus and his fellow researchers harnessed the power of technology to map, as the Nobel committee put it in honoring them, ‘the mysterious ways of chemistry.’ In so doing, they reached beyond the boundaries of conventional thinking in chemistry to align the workings of classical physics with quantum physics, and they provided the scientific community with crucial tools that have enabled many of the advances made in contemporary chemistry.”

The other living honorees in the department are E.J. Corey, the Sheldon Emery Professor of Organic Chemistry Emeritus, who won in 1990, and Dudley Herschbach, the Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of Science Emeritus, who won in 1986. Herschbach has a first-floor office across from Karplus in the Edward Mallinckrodt Chemical Laboratory.

For Karplus, the constantly ringing telephone at home was just the start of a day that already seemed long by 11 a.m. That was when faculty and other well-wishers gathered for a champagne toast to him in the Chemistry Library at Converse Memorial Laboratory.

While the crowd was still gathering, Jerome V. Connors, associate director of laboratories at the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, provided a thumbnail of Karplus’ research on predicting the motions and reactions within molecules that make them perform useful functions. The honoree’s work began in the 1970s with simple molecules and evolved to larger ones as the computers that he relied on for calculations got faster and more powerful. Now, Connors said, “you can actually do simulations in a computer instead of at the lab.”

Karplus first arrived there in 1966, after teaching stints at the University of Illinois, Columbia University, the University of Paris, and elsewhere.

He has co-authored four books and has written 811 published articles, the first of which appeared in 1947 when he was 17. That was on Massachusetts alcids, a name for web-footed diving birds. A birding trip to Alaska that year offered his first scientific observational challenges and sharpened his eye for what became his passionate avocation: photography. (A show of his photos in Paris just closed, and he maintains a non-academic website.)

For the champagne toast with colleagues, Karplus had added a maroon sweater to his morning wardrobe. He walked into the library to loud applause. “Champagne?” someone offered, adding as a joke, “Is it your first?” The modest Karplus looked down, saying, “My first Nobel Prize.”

“Finally it happened,” said Corey. “I knew it would happen.”

Harvard Provost Alan Garber had a dozen roses for Karplus and greetings from Faust. “You won the beauty pageant, we heard,” he said.

Corey remembered a conversation decades ago with Pauling, who won the chemistry Nobel in 1954 and the Peace Prize in 1962. Pauling told Corey that Karplus “was my most brilliant student.” Corey added, “Pauling, as usual, was right.”

On hand were at least two theoretical chemists, as Karplus is. Eugene Shakhnovich now runs his own chemistry and chemical biology lab at Harvard. And Eric Heller, the Abbott and James Lawrence Professor of Chemistry and Professor of Physics, is a longtime Karplus friend. Heller remembered a winter day when Karplus had trudged in to work, forgetting his notes. Then came a brilliant ad hoc lecture, Heller said, and “at that moment I knew you’d get the Nobel Prize.”

Heller and Shakhnovich joined in a leitmotif that appeared in every toast: What took so long? “It was late in coming,” said Robert Petrella, a project scientist with the Karplus Research Group. “But we all expected it for years.”

In the welcoming crowd was Efthimios “Tim” Kaxiras, the John Hasbrouck Van Vleck Professor of Pure and Applied Physics, who has appointments in physics, applied physics, and chemistry. He explained the wide appeal and influence in Karplus’ simulation work in those and allied fields.

“His work answers some fundamental aspects of physics, how to model systems for very long time scales.” At the level of atoms, things happen 12 times the magnitude faster than events at the cellular level, which can be measured in milliseconds. So events at the scale of atoms have to be simulated for long enough that cellular processes can be glimpsed and understood.

“It’s all these little events that add up,” said Kaxiras, and “which, of course, is what drives life.”

By 1 p.m., still without lunch, Karplus stepped in front of a crowd of journalists for his press conference.

“My chemistry colleagues thought it was a waste of time,” he said of his early work in using computers to simulate molecular processes. “Now it has become a central part of chemistry and structural biology. … It has consecrated this field.”

There’s a lesson in his story for young scientists, said Karplus: Persist, and believe in your vision even if it defies an accepted norm. “Originality and hard work are the two things that are important,” he said.

When Karplus was a boy, he recalled, his older brother got a chemistry set. He had wanted one too but got a microscope instead, because his parents didn’t want both boys perhaps setting off small explosions. (“The feeling was that two chemistry sets in the family would be too much,” he explained.) Disappointed at first, he discovered rotifers and watched their rotor-headed gyrations for hours in the microscope, which opened his eyes to the wonders of science.

His family had escaped the Nazi takeover of Austria in 1938 by slipping out of the country to Switzerland. After six months of school there, he moved with his family to Boston, and then to Newton. (His boyhood figured in “Spinach on the Ceiling,” an autobiographical essay that Karplus wrote in 2006 for the “Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure.”)

“I was supposed to be a doctor,” he said. “We had one or two in every generation.” But at Harvard in the fall of 1947, a freshman chemistry class with Professor Leonard K. Nash changed his life, awakening in him the idea that to understand biology he had to understand the physics and chemistry on which life depended.

While an undergraduate, Karplus also worked with George Wald, performing calculations relating to his vision experiments that by 1967 led to Wald’s share of the Nobel Prize in medicine or physiology.

When Karplus eventually worked with Pauling, the legendary chemist not only taught Karplus about the importance of intuition in research, but underscored a feeling that the young researcher had that it was important to dive deep into life’s fundamental processes at a cellular level, as well as into “the logic” of structure there.

Karplus is modest, energetic, and imaginative; he has perspective too. After the celebrations, he was soon planning dinner, expecting that he would enjoy it with just his family, without the phone ringing. Planning of that kind is familiar to Karplus, an amateur chef who for years during vacations volunteered to work in the kitchens of three-star restaurants in France and Spain.

On his walk home from work each afternoon, he said, that night’s dinner menu occupies his thoughts. Tonight, he said, the menu would include a fine bottle of wine bought 25 years ago for “a special occasion,” flank steak, and fresh corn off the cob, perhaps with a cream sauce.

With the cameras off and the room now quiet, Karplus offered a final thought on his Nobel day. “The only real chemistry I do,” he said, “is in the kitchen.”