Renée Mussai (pictured) and Mark Sealy selected 200 photographs for “The Paris Albums 1900: W.E.B Du Bois” exhibition (photo 1). The images were among the 363 originally displayed by Du Bois at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900. “Du Bois was mounting this exhibition to fight back visually against images of black people as animals, bestial, deracinated, ignorant,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr. (photo 2).

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Black like we

In exhibit of century-old photos, African-Americans defined their own essence

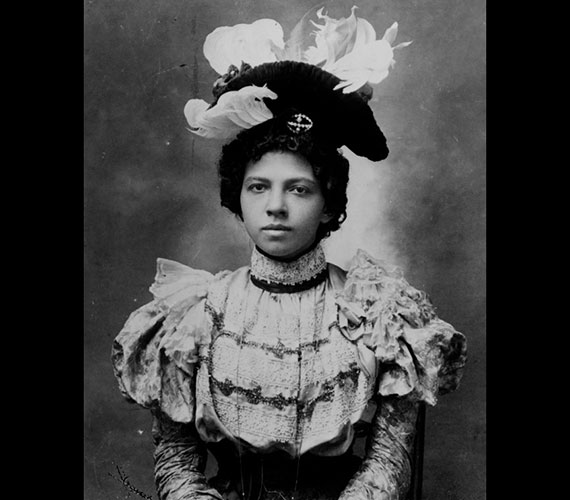

Egret plume in her hair, the lady is the picture of elegant sophistication, a Gibson Girl in sepia. Her hair piled high upon her head, she wears earrings, choker, and brooch. She faces slightly to the right, her head cocked. She’s not really smiling. Rather, her look is dignified.

This portrait of a fashionable young black woman is among 363 photographs of African-Americans that were included in an “American Negro” exhibit that sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois helped organize for the Paris World’s Fair of 1900.

‘The Paris Albums’

W.E.B. Du Bois and Thomas J Calloway assembled 363 photographs for the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle. Photos courtesy of the Prints & Photographs Division/Library of Congress

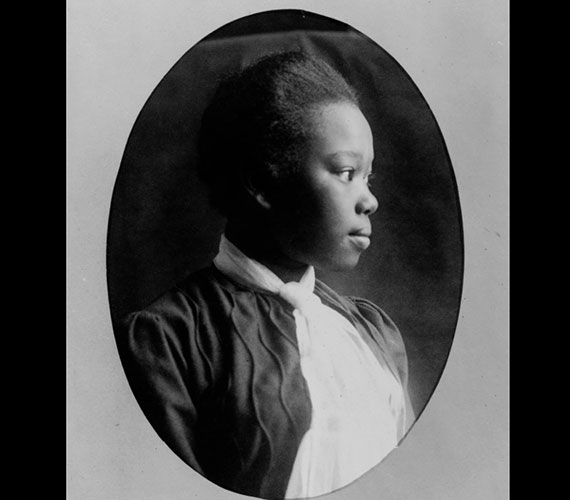

The portraits provide an extraordinary insight into the conditions of black culture at the end of the 19th century, only 35 years after the abolition of slavery.

![Sitters were presented unidentified and photographers unnamed; a typical caption would read "African-American [man], head-and-shoulders portrait ..."](https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/du-bois-exhibit-3.jpg)

Sitters were presented unidentified and photographers unnamed; a typical caption would read “African-American [man], head-and-shoulders portrait …”

She and the other photographic subjects were “performing” their class, their prosperity, and at the same time their blackness, said Deborah Willis, chair of photography and imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. She spoke during a panel discussion Thursday that was part of the opening of an exhibition of the photographs at Harvard.

Two hundred portraits were selected for the exhibition by the British-based photographic arts agency Autograph ABP and the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard. “The Paris Albums 1900: W.E.B Du Bois,” curated by Mark Sealy and Renée Mussai, runs through December at the Neil L. and Angelica Zander Rudenstine Gallery at the Hutchins Center, 104 Mt. Auburn St.

In the portraits, Willis said of the participants, “They’re performing the New Negro.”

The images of educated and industrious middle-class African-Americans that Du Bois chose for the Paris exhibit were meant to stand in sharp contrast to the racist depictions of blacks prevalent in 1890s America.

Du Bois said at the time that visitors to the World’s Fair exhibit would find “several volumes of photographs of typical Negro faces, which hardly square with conventional American ideas.” The aim, he said, was to present “an honest straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.”

The pictures of black culture in America only 35 years after the abolition of slavery represented a “visual construction of a new African-American identity,” say organizers of the Harvard exhibition.

The panel discussion, “Vanguards of Culture: W.E.B. Du Bois, Photography, and the Right to Recognition,” was hosted by the Hiphop Archive in the Hutchins Center at the W.E.B. Du Bois Research Center. The panelists included Willis; Nana Adusei-Poku, applied research professor in cultural diversity at the Willem de Kooning Academy at Rotterdam University and a lecturer in media arts at the University of the Arts, Zurich; and Kimberly Juanita Brown, assistant professor of English at Northeastern University. Mussai, a curator at Autograph ABP, gave some opening remarks, and her colleague, Sealy, offered commentary via video link.

The presentation, said Lawrence Bobo, the W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Social Sciences at Harvard and founding editor of the Du Bois Review, brought to a modern audience “the complexities and challenges of representing blackness and black people.”

Positive depictions of accomplished and prosperous black people were uncommon in Western culture at the time that Du Bois, the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, helped organize the Paris exhibit. But visitors to the exhibit, which also included a statue of African-American leader Frederick Douglass and displays of black progress, also passed through a midway where Dahomey tribesmen from Africa were displayed as if in a human zoo, Willis said.

Portrayals of blacks were particularly negative in the popular culture of the United States. There, the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson ruling in 1896 had upheld legal segregation and propelled the rigid affirmation of Jim Crow laws, accompanied by a proliferation of racist images in advertising and popular art, said Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor at Harvard and director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, who introduced the panel discussion.

“Du Bois was mounting this exhibition to fight back visually against images of black people as animals, bestial, deracinated, ignorant,” Gates said. In direct contrast to the National Geographic-style presentation of African tribespeople on the fairgrounds, Gates said, these photos showed black people as “partakers of culture.”

The Hiphop Archive was an especially fitting venue for the discussion, said its executive director Marcyliena Morgan, professor of African and African American studies at Harvard, because, in his own way, the stiff-collared scholar Du Bois challenged convention in his 1900 exhibit, as something like a precursor to the modern hiphop movement.

“This notion of photos, and the pose, and what it means, is so much a part of hiphop,” Morgan said. “The importance of representation and the body is in many respects at the heart of it. In hiphop, most artists want to redefine their experience or the way society is looking at [it].”

Bobo agreed, saying, “He certainly thought of himself as representing and challenging, which is precisely what many hiphop artists are doing.”

“The Paris Albums 1900: W.E.B. Du Bois” is on display at the Neil L. and Angelica Zander Rudenstine Gallery through December.