Henry Louis Gates Jr. (left), the event’s host and director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, shared a moment with medal recipient Steven Spielberg (photo 1). Gov. Deval Patrick garnered laughter during his introduction (photo 2). Sonia Sotomayor (from left), David Stern, and Tony Kushner didn’t let the evening’s lighter moments pass them by either (photo 3).

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

At Du Bois awards, the stars aligned

Medal recipients include Sotomayor, Kushner, Spielberg, Lewis, Jarrett, and Stern

When the stars come out, it is not always nighttime. Take, for instance, the W.E.B. Du Bois Medal ceremony on Wednesday afternoon at Sanders Theatre.

The six medalists included a White House adviser (Valerie Jarrett), a playwright with a Pulitzer Prize (Tony Kushner), a U.S. representative called “the conscious of Congress” (John Lewis), an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (Sonia Sotomayor), the commissioner of the National Basketball Association (David Stern), and a Hollywood director with three Oscars (Steven Spielberg).

The medals, awarded since 2000, go to writers, artists, philanthropists, and others for outstanding contributions to African-American culture.

Jarrett and Lewis did not attend because of this week’s shutdown crisis in Washington, D.C. “It’s one thing for our Republican friends to shut down the government,” mused Henry Louis Gates Jr., the event’s host and director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research. “It’s another to disrupt this ceremony.”

Even those introducing the medalists had star power. In the front were Harvard Law School Dean Martha Minow and NBA Hall of Fame player Bill Russell. Nearby was Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick, Harvard President Drew Faust, and Tony Award winner Diane Paulus, artistic director of the American Repertory Theater.

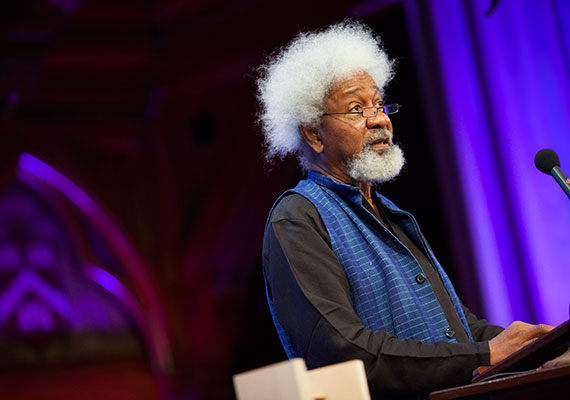

Also in the front row, ready to present one of four readings from W.E.B. Du Bois, was Wole Soyinka, the 1986 recipient of the Nobel Prize in literature and the first African laureate. He is a Hutchins Fellow at the new Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

The center, with Gates as its first director, was itself a star of the event, which marked its inauguration. The center brings under one roof the W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute, the Hiphop Archive & Research Institute, the Image of the Black Archive & Library, the Du Bois Review, Transition Magazine, the Neil L. and Angelica Zander Rudenstine Gallery, and the Hutchins Family Library. Four new entities will reside at the center, too: the Afro-Latin American Research Institute, the History Design Studio, the Program for the Study of Race & Gender in Science and Medicine, and the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art.

The center made Glenn H. Hutchins ’77, J.D.-M.B.A. ’83, yet another star. He endowed the Hutchins Family Foundation, which made the center possible with a gift of $15 million.

Gates, who is also the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor at Harvard University, started the ceremony with a long historical introduction on African-Americans at the University, a look at “fair Harvard,” he said, “and not-so-fair Harvard,” where there were no black graduates of the College for its first 234 years. (The first was Richard T. Greener in 1870. The first professional degrees — in law, medicine, and dentistry — had been awarded to three black men the year before.)

Gates also made much of Sanders, sketching an arc of progress from 1869 to the present. It was in “this august space,” he said, that “two seminal events” took place more than a century ago, putting Harvard on a path to racial justice: an 1890 Commencement address by Du Bois (on Jefferson Davis), and, in 1896, the first Harvard honorary degree conferred on a black man, Booker T. Washington. (The year before, Du Bois had become Harvard’s first African-American Ph.D.)

Hutchins took the podium next, thanking Gates after his lengthy history lesson for “the wonderful words,” and then promising — to laughter — to say fewer of them. Apologizing to Spielberg, he showed a video about the Hutchins Center.

That too was a star-heavy production, featuring Harvard’s William Julius Wilson, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, and Lawrence D. Bobo, all of whom did readings from Du Bois during the ceremony. Also on screen were Faust, Lawrence Summers, Neil Rudenstine, Robert Rubin, Robert D. Reischauer, Dean Michael D. Smith of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and Marcyliena Morgan, executive director of the Hiphop Archive.

Bobo, Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Social Sciences, struck at the canard that Africa was a continent that had not contributed much to world culture. “This is one of the places,” he said of the center, “correcting the deep error of that assumption.”

Introducing the first medalist, Patrick apologized on behalf of Jarrett, a key White House player in President Obama’s domestic agenda. She had looked forward to being at Harvard, he read from a note she had sent, since it would take her “outside the madness of Washington, D.C.”

Paulus introduced Kushner, praising him for his “fierce intellect,” his “wild imagination, and deep, deep compassion,” and noting his numerous awards, including a Pulitzer, two Tonys, three Obies, and, earlier this year, the National Medal of Arts and Humanities. The Du Bois medal “is named after one of my heroes,” said Kushner, and was bestowed by another, Gates.

Stern is retiring next year after 30 years running the NBA. A towering Russell, age 79 and sporting a gray goatee, rose from his front-row seat and loped slowly across the stage to introduce him. “A few years ago, I used to send checks” to Harvard, said Russell, a reference to his youngest daughter’s years at Harvard Law School. At her graduation, he said, she asked him to take a picture — so he turned his pockets inside out.

As for the commissioner, “One of the highest honors I received as a man was to talk about David Stern,” said Russell, praising him for his respect for players and for his commitment to community service. “He’s made a lot of money for the NBA. But that is not the agenda. The agenda is to be good citizens.”

“That’s one of the great honors, to be introduced by Bill Russell,” Stern said of the 12-time All-Star. Stern took a moment to marvel at Russell’s career, which began in a vanished age of basketball road games in segregated communities, “when Bill couldn’t eat and sleep with his teammates.”

When Minow introduced Sotomayor, she said the medal was going not only to an accomplished jurist, but “to Sonia from the Bronx.” Sanders lit up with cheers.

Sotomayor is “intellectually demanding,” said Minow of “my classmate, my friend, my hero,” but “she is also the justice who knows all the names of the cafeteria workers,” a down-to-earth champion of demystifying the law, including a primer on what judges do for an episode of “Sesame Street.”

At the podium, Sotomayor said Minow had illustrated an important piece of advice: “Always invite a friend to give your introductions.”

Sotomayor also remarked on the pioneers of racial justice who figured in Gates’ introductory historical remarks. “I never stood alone,” she said of her own rise from a working-class childhood. “I stand on the shoulders of all those men and women.”

Hutchins discussed Lewis, a veteran of the Civil Rights Movement who by age 23 had been arrested 24 times and who in 1963 was the youngest speaker during the famed March on Washington. He is the only surviving speaker from the day of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Faust introduced the last medalist, Spielberg, whose four decades of moviemaking “have shaped our lives,” she said, with visions of “hope, beauty, excitement, and nobility.”

Spielberg’s remarks were the briefest, and started with a memory of 2012, when his film “Lincoln” had just been released and reviews were starting to roll in. “The only thing I cared about,” he said, was “What does Skip Gates think of my movie?”

As for the Du Bois award, Spielberg summed up the collective bravery of all who came before in the fight for racial justice. “Nothing gets done,” he said, “unless we’re all going uphill.”