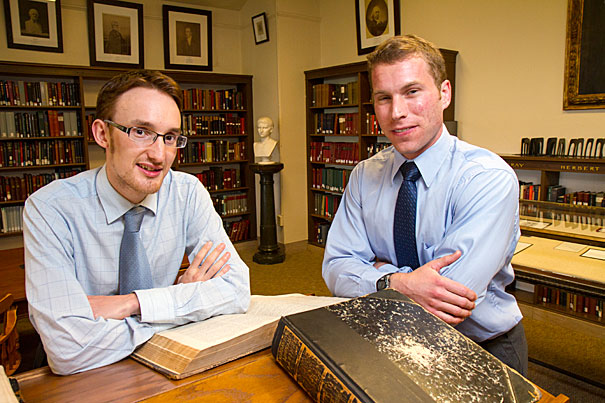

Last year, Ph.D. student Stuart M. McManus (left) discovered a poem by Benjamin Larnell, the last Native American student at Harvard in the colonial era. Larnell’s poem is most interesting for what it signifies, said Tom Keeline, a scholar of Latin pedagogy: “that American Indians were trained in exactly the same way as colonial Puritans.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard’s Indian College poet

After 300 years, researcher finds Latin ode by last of its students

For nearly 300 years, Harvard student Benjamin Larnell (c. 1694–1714) was simply a footnote to scholars of Native American history. They knew that he was the last student of the colonial era associated with Harvard’s Indian College, that he died from fever before graduating with the Class of 1716, that he liked to socialize and fight, and that he was an accomplished student poet.

“He gets a footnote in every book,” said Stuart M. McManus, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in history at Harvard. “He was known to be very good (at poetry), but we didn’t have any evidence of this.”

Until now, that is. Last year, McManus found a Latin poem by Larnell, a single page that not only shows competence and creative promise, but also gives scholars a rare window into the classrooms of pre-Revolutionary America. A study of the poem, co-authored with fifth-year Classics graduate student Tom Keeline, will appear next spring in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology.

McManus is writing his dissertation on how Ciceronian Latin rhetoric was the pedagogical lodestar of humanistic learning from the Middle Ages onward, how it was exported to the disparate cultures of the European colonies, and how it changed in those new contexts. His research in colonial-era archives throughout the world involves “looking for anything written in Latin, basically,” he said.

Last year, McManus was scouring catalog entries at the Massachusetts Historical Society when he discovered the poem by a student who soon went on to Harvard’s Indian College. “I had no idea who Benjamin Larnell was,” he said.

Larnell, he soon found out, was the fifth and last Native American student at Harvard in the colonial era. Only one graduated, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, in 1665. (His classmate Joel Iacoomes, who died just before graduating, received his A.B. in a special Commencement ceremony in 2011. Another Indian student of that era died of smallpox; one left Harvard to become a mariner.)

Most of the Larnell footnotes, said McManus, include oft-quoted praise from Harvard President John Leverett, who called the teenager “an acute grammarian, an extraordinary Latin poet, and a good Greek one.”

The poem itself

Larnell’s poem, “Fable of the Fox and the Weasel,” now joins just two other examples of Native American writing in classical languages from the days of the Harvard Indian College: elegiac couplets in Latin and Greek by undergraduate Eleazar, who died in 1678, and a Latin address that Cheeshahteaumuck wrote to English benefactors of Harvard.

Larnell was likely 15 or 16 when he wrote this newly discovered (but undated) poem. He was a student at Boston Latin School, where he was precocious enough to skip two of seven grades, and where he preceded Benjamin Franklin by a few years.

“It’s a school assignment, not a romantic outpouring of feelings,” said Keeline, who finely parsed the Larnell poem’s metrics, grammar, and classical influences, which included Horace and Virgil. “It’s competent, it shows occasional flair, and in comparison to his contemporaries, he is at or above their level.”

By the time Larnell attended Harvard, he appears to have been well ahead of most of his contemporaries in writing verse in classical languages. At the time, versification was required to get into Harvard, but not required in College studies. Yet this young student from a native village near Taunton, Mass., spent time writing verse not only in Latin, but in Greek and Hebrew as well.

Larnell’s poem is a Latin versification of the “Fable of the Fox and the Weasel,” a familiar prose parable from Aesop, the ancient Greek fabulist. Aesop’s tales, simply written but rich in complex moral lessons, were a mainstay for centuries of students learning classical languages. In this story, a fox, thin with hunger, creeps through a crack into a bin filled with grain. But after eating until his belly is full, he no longer can get out. The tale is a testament to how hard it is for the rich to be free of fear and anxiety. “You must return through the narrow hole as skinny as when you entered it,” advises a weasel, since “many people (are) happy in their poverty, and well-supplied.”

Judge Samuel Sewell, a Larnell benefactor better known for his role at the Salem Witch Trials two decades earlier, wrote a letter to a friend in London, enclosing a poem that Larnell had written in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew — proof, Sewell said, that educating Native Americans was working. The letter survives, but the tri-lingual poem — “sadly,” said McManus — does not.

Larnell’s newly discovered poem is most interesting for what it signifies, said Keeline, a scholar of Latin pedagogy: “that American Indians were trained in exactly the same way as colonial Puritans.”

The training in Latin and Greek that Larnell got was the same as that of other colonial schoolboys — and it in turn was the same as that of English schoolboys preparing for Oxford and Cambridge. “People (were) trying to create scholars,” said McManus, “who could do what the ancients did. It’s the long shadow of the Renaissance.”

Larnell’s poem comes with a discovery that “humanistic culture survived so late,” he said — right to the eve of the Enlightenment — and that it was foundational to Franklin and his Revolutionary American contemporaries. “These things which seem obscure (today) are really the foundation of their intellectual world.”

Around the time of the American Revolution, speeches were still being delivered in the style of Cicero, though no longer in Latin itself, said McManus, a student of what he called “the long shadow of Cicero across the whole world.” That shadow includes the annual speeches delivered in memory of the 1770 Boston Massacre, a tradition that became the rhetorical template of Fourth of July orations. “This (classical) education was basically the education of the Founding Fathers,” he said.

Profit in this world

Today, arguments for teaching the classics and the humanities in general seem “phrased in idealistic terms,” said Keeline; arguments against, meanwhile, seem to hinge on their alleged impracticality. But in Larnell’s day, “There was very much a sense these were practical things. You would give a better sermon on Sunday. There really was a sense this would bring you profit in this world.”

Latin was also the outward sign of an educated man, said McManus. In Larnell’s era, original Latin verses were given as gifts. At funerals and elsewhere, Latin “was a suitable, prestigious way to honor someone in the Roman style,” he said.

Classical languages gave ministers-in-training at places like Harvard “direct access to the Bible,” McManus added, schooled them in rhetoric, and gave them “tools to be a better person, to be a better scholar, and to be a better Christian.” In the New England of 300 years ago, these were not lighthearted considerations, said Keeline. “This was about saving souls. This was eternal life.”

Sewell believed in his protégé’s potential for converting Native Americans to Christianity. But when Larnell died, there came “a great frown upon the work of gospelling [cq] the Indians,” the judge noted in his diary, “that all attempts to educate one of their own Nation have prov’d abhortive.”

In his day, Larnell commanded respect and attention. Walking beside his casket at Boston’s Granary Burial Ground were the president of Harvard, two fellows of the College, Sewell, and commissioners of the Company for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England. At the funeral too was Joshua Gee, Class of 1717, a Harvard schoolmate whom Larnell had once kicked in a fight (which once got him dismissed from the School for eight months). Today, there is no record of Larnell’s grave, or of a headstone, if there ever had been one.

An idea fades

It is fair to say that the death of Larnell was likely the death knell for Harvard’s six-decade attempt to educate the native sons of New England. “The original impetus was beginning to fade,” said McManus.

It didn’t help that King Philip’s War of several decades before had made Indians more suspect, he said, nor that the Indian College itself — a building near present-day Matthews Hall — had been torn down, nor that benefactors were hard to come by. (Larnell paid no tuition thanks to the Boyle fund, a legacy of Robert Boyle, the founder of modern chemistry.)

With the discovery of the Larnell poem, scholars will be “happy another piece of the jigsaw has been put together,” said McManus, and that a perennial footnote is now a full poem and the grist of long essays to come. They will also be happy to see an example of early colonial schoolwork, “a window into the colonial classroom,” said Keeline, “that allows us to marry up the practice with the theory of colonial education.”

Meanwhile, readers outside academe will be stunned to be reminded that native students were trained to this level, were taught the same way as their English schoolmates, and that — in the case of Larnell — such erudition could come at such an early age to a person whose first language was neither English nor even an Indo-European language.

The teenager from another culture who succeeded as he did at Harvard was to some extent just a measure of that vanished era’s rigorous schoolboy culture. The “grammar grind” — a refinement of training over centuries — was in the end “just practice,” said Keeline. McManus added, “If you wanted to go to college and become a minister, you had to do this.”

But both young scholars acknowledged there was something exceptional about Larnell. Barely past his mid-teens, he read, wrote, and spoke Latin and Greek. He read and wrote Hebrew. And he wrote verse in all three. At some level, admitted Keeline, “You should be shocked, a little bit.”