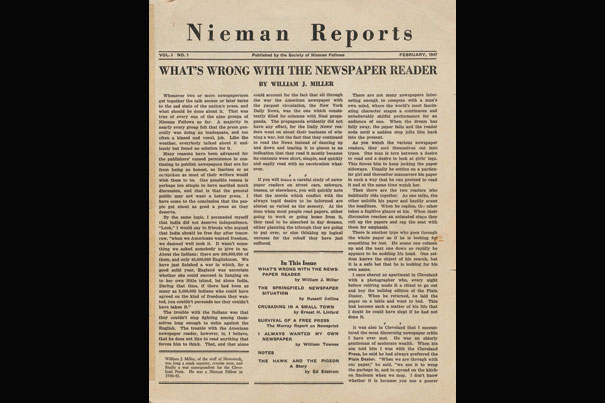

The Nieman Foundation celebrates 75 years. Looking back, a 1947 issue of Nieman Reports asks: “What’s wrong with the newspaper reader” (photo 1); the 1939 class of Nieman Fellows (photo 2); and Nieman curator Ann Marie Lipinski (photo 3).

Courtesy of the Nieman Foundation; Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

75 and getting younger

Nieman Foundation for Journalism evolves to meet changing times

In 1936, with the United States embroiled in the Great Depression and the world unsettled by Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, an unexpected gift landed on the desk of Harvard President James B. Conant, a present that would have far-reaching implications.

It was a letter from the lawyer for Agnes Wahl Nieman, a little-known Milwaukee widow whose husband had owned a local newspaper, notifying Conant that she had left the bulk of her estate, about $1.4 million, to Harvard. The bequest came with what was then considered a curious stipulation: “To educate persons deemed specially qualified for journalism.”

Despite a few initial misgivings about whether newspaper reporters properly belonged among University scholars, Nieman’s gift eventually financed an annual fellowship program that became the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard.

The foundation, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this weekend, is still perhaps best known for its 10-month fellowship program, which brings top writers, photographers and editorial cartoonists from around the world to Cambridge to study and work on special projects free from the pressure of daily news deadlines.

Over the years, the fellows have included many of the profession’s most distinguished figures, including Pulitzer Prize winners Anthony Lewis ’57, the late legal writer for The New York Times; J. Anthony Lukas ’69, the late author and Times reporter; and biographer Robert Caro ’66, who will speak at this weekend’s anniversary celebration.

Nieman Curator Ann Marie Lipinski said satisfying a “craving for knowledge” and “finding the soul of their career” are still what motivates those who come here, just as they were seven decades ago. “For some of them, it’s a eureka moment, like it was for Caro,” whose studies of urban planning would later inform his monumental 1975 biography on Robert Moses, “The Power Broker.” “For others, it’s just this deepening sense of who they are as journalists, this individual growth as a leader,” she said.

In 2010, freelance journalist Laura Amico launched Homicide Watch D.C., a groundbreaking website that tracked every murder in Washington, D.C. After finding great demand from news editors who wanted to replicate Homicide Watch’s data-rich storytelling in their newsrooms and not knowing how to pursue those opportunities, Amico came to Harvard as one of two inaugural fellows in a new joint partnership between Nieman and the Berkman Center for Internet & Society last fall, looking for entrepreneurial expertise and human connection.

“Because I had been on my own for so long, I had a sense of how valuable fellowship was, but I didn’t really know or remember,” said Amico. “And it’s not just about making friends, it was also about finding mentors who were able to be there for conversations over coffee or lunch, or just passing in the hallway — conversations that you don’t have when you’re working from your kitchen table. When you’re in a community with other people, they become so important for how you think about the work that you’re doing and the work that you want to do.”

While camaraderie and collaboration are still an important part of the core mission, the foundation has evolved to meet the rapidly changing roles of today’s journalist, said Lipinski, herself a 1990 fellow. Given the new demands of the digital era, fellows now come not only to delve deeply into a particular story or to engage with peers, but to enhance skills in video, photography, audio, and broadcasting, to learn entrepreneurship, and to train in leadership and negotiation.

“This idea that you’re one thing — that you’re a writer, you’re an editor, you’re a photographer — is just not a successful model for most journalists anymore,” Lipinski said. A number of recent fellows, for example, have been engineers developing software that quickly identifies and culls useful information from social media for reporters and editors.

“We want Nieman to be a crossroads for that and to have anybody who’s working on some aspect of enhancing journalism’s future to be absolutely at home here,” said Lipinski.

In addition to Nieman Reports, a quarterly magazine with work by current and former fellows and other top journalists, and Nieman Storyboard, a publication that showcases the craft of narrative storytelling, the Nieman brand has earned new and broad exposure from the growing profile of the Nieman Journalism Lab, a website that collects and promotes news and ideas about the craft’s digital future.

“The Nieman Lab has really become the premier spot to keep up on how technology is changing journalism [and] how journalism is able to take advantage of technological change,” said Dan Kennedy, an assistant professor of journalism at Northeastern University and the author of “The Wired City: Reimagining Journalism and Civic Life in the Post-Newspaper Age.” “It’s just an invaluable resource. It’s something I assign to my students to keep up on during the semester.”

Kennedy, who periodically writes for the Lab as an unpaid contributor, praised its unique “single-minded focus on journalism and technology.”

John Harwood, chairman of the Nieman Advisory Board and also a 1990 fellow, said that as the news business contracts and expands in new directions, the board continues to focus on making sure the foundation best serves the changing needs of journalists.

“It’s a legitimate concern, and it’s incumbent on us to make that 10-month experience relevant,” said Harwood, chief Washington correspondent for CNBC and a political writer for The New York Times.

The “pressing issue” for the board, he said, is “Can we preserve the pristine character of a learning-for-learning-sake year, an enrichment-for-enrichment-sake year that has really characterized the fellowship from the beginning? To the extent that there are more existential pressures on journalism, the ability to preserve that is challenged,” he said. “That doesn’t mean we can’t do it, but we’ve got to make sure that we do it in the right way and in a smart way.”

To counter any perception that the foundation’s resources only help a select few, Lipinski said it has begun to open the Walter Lippmann House to the wider University and the Cambridge-Boston community, hosting broader events such as book readings by author Junot Díaz and a town hall-style forum last spring about the role Twitter played in reporting on the Boston Marathon bombings. The session featured key news editors and reporters who were covering the still-unfolding story.

“That’s what makes this an exciting place right now — that we’re not outside the conversation. We’re very much at the center of it and want to be more and more,” said Lipinski. “We want people to say, ‘Maybe Nieman will do something on that’ [and], that you’ll turn to Nieman for discussions about what’s happening in the journalism universe.”