McKay School teacher Brianna Guilford (hat) prepared students Denny Diaz (from left), Andy Reyes, Carol Cruz, Edwin Bacquedano, Christian Tellez, and Alondra Leon to find an outdoor setting for a reading from the classic, “The Wizard of Oz.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The story deepens

Developed by Harvard professor, Pre-Texts strengthens Boston students’ connection to language, characters

At East Boston’s McKay School, Brianna Guilford led her class of tin men, cowardly lions, Dorothys, and scarecrows into the sunlight.

“We’re reading ‘The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,’ the original story, and they’re exploring and interpreting the story through the creative arts using a program called Pre-Texts,” she said, as the students ran outside. Having created masks and costumes inspired by the L. Frank Baum story, the children were seeking a real-world setting related to the chapter they were reading, as a way to deepen their connection with the characters and story.

The activity wasn’t just for fun, but was meant to help the students, for whom English is a second language, become stronger readers and English speakers. In addition, “Oz” is a fourth-grade-level text — well above the supposed reading level of Guilford’s second-graders.

Backed by the Boston Public Schools (BPS), Pre-Texts was developed by Doris Sommer, the Ira and Jewell Williams Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and director of the Cultural Agents Initiative at Harvard. The program, now in its third year, has been a big success — this summer it was featured systemwide in programming for English-language learners [ELL], serving more than 1,000 students. In the fall, Pre-Texts will expand to 1,500 students in the BPS after-school program.

By encouraging wider creative exploration, Pre-Texts allows students a “level of ownership” with the text, and helps to animate the story, Guilford said.

From words to action

Student Denny Diaz, (from left) McKay School teacher, Brianna Guilford (green triangle hat), Andy Reyes, and Carol Cruz perform an activity based on the Wizard of Oz book read in class as part of the Pretext program inside the McKay School in East Boston. The program began at Harvard and has been implemented in Boston Public Schools’ English Language Learners summer school programs. Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

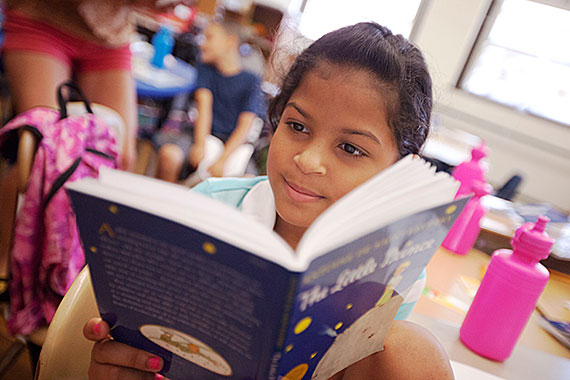

On display in the halls at the McKay School, a colorful Andy Warhol-style tableau depicts the emotions of “The Little Prince” as seen by students who read the novella.

Alondra Ruiz chooses a passage from “The Little Prince” to perform. Students with the ELL program at the McKay School in East Boston studied the book this summer and interpreted passages using different artistic approaches.

Alondra Ruiz (left) and Carla Meja-Hernandez act out a passage from “The Little Prince” as teacher Betzy Lazo looks on. Visual art and drama are Pre-Texts strategies McKay teachers used this summer to help students understand and “own” these classic texts.

In this Pre-Texts activity on display at the McKay School, students created collages illustrating vocabulary words they learned while reading “The Little Prince.” The students then had to guess what the words were based on the images.

McKay School students Sarah Martinez (left) and Emily Depina use sounds and homemade instruments to interpret a passage they read in “The Little Prince.”

Alondra Ruiz (right) and her teacher Betzy Lazo read “The Little Prince.”

Student Denny Diaz prepares to act out his part as the Tin Man in “The Wizard of Oz.”

McKay School teacher Amy Blenk (from left) works with students Sarah Martinez, Emily Depina, and Omar Posada, who made musical instruments out of rock-filled cups to interpret a passage in “The Little Prince” with sound.

McKay School teacher Christine Valenti shows her students’ different perspectives from “The Wizard of Oz.”

“The interactive piece is very, very big,” she said. “That brings deeper comprehension, building a personal relationship to the text, understanding connections between characters, setting, and language, as well as establishing a common ground that is essential for ELL students.”

A student who combines reading with activities such as drawing, creating masks, improvising scenes, and even inventing new characters is engaging the intellect in a profound way, said Eileen de los Reyes, deputy superintendent of academics with Boston Public Schools.

As a result, students engage with the text on a deeper and more complex level, as they view the text through multiple points of view and dimensions.

“Students who participate in Pre-Texts are in a much better position to move forward. The magic of Pre-Texts is that it engages the reader with the text in a way that you don’t even realize how hard, and how deeply, you are thinking. It allows the reader to do heavy lifting, intellectually, and have great fun at the same time — and the children really respond to that.”

De los Reyes added that another benefit of the program is how others see the students as more-sophisticated readers, noticing their complex interpretations of the story. “It’s an amazing thing to see,” she said. “Teachers and family members see these students in a new light, because it seemed impossible that they could do this. But Pre-Texts is such a dynamic learning tool that it empowers the children to engage with the text, reconstruct it, and deconstruct it. It’s a real equalizer.”

De los Reyes noted that it was Sommer who first approached BPS with the idea of bringing Pre-Texts to local schools, adding that it’s “an example of the very powerful collaboration” between Boston schools and Harvard.

“She’s a very special intellectual,” de los Reyes said. “The modeling and the guidance for this project come directly from her, in a very hands-on kind of way. She’s been very persistent and very dedicated with it. She’s a true partner, and her love of the work, the program, and the children is very clear.”

For Sommer, the idea for Pre-Texts began in 2006, when in the course of leading a Cultural Agents summer program in Lima she encountered cartonera (cardboard) publishers, who create books out of recyclable materials. That a reader’s own creativity could deepen engagement with the text was a crucial revelation.

“I realized that the best way to teach was to use books as raw material for making other works of art,” Sommer said. “It made sense of all the literary fury and theory that I had been researching and teaching. Essentially, it’s borrowing other people’s words and recombining them to make your own art.”

In fact, Sommer argues, far from being a decorative or expressive tool, the act of creative exploration is fundamental to the program’s success, and that success needn’t have limits.

“As Harvard President Drew Faust has observed, art-making should be part of academic learning,” she said. “The reason that art is the vehicle for higher-order learning is because it’s a vehicle for exploration. What we’ve found is that when hardworking students of any level engage with Pre-Texts, it’s a brilliant exercise. Whether privileged or not, whether undereducated or not, every student flourishes in this program.”

The excitement, the passion, and the dedication generated when people make art, Sommer said, is “a motor that we have underestimated in education. We don’t take advantage of the passion and the dedication of time demanded by creating these works of art.”

In addition, Sommer said, Pre-Texts facilitates an appreciation for other points of view, helping to develop “sturdy, collaborative citizenship” in the classroom — an achievement that cannot help but have a ripple effect outside of it.

“When you generate admiration for others’ work, then it’s the variety and diversity that keeps you exploring,” she said. “It’s not tolerance: tolerance is just waiting for the other person to stop talking. But if you really, literally begin to appreciate and admire diversity, you begin to depend on one another to keep that variety alive.”

Ultimately, the proof of Pre-Texts’ effectiveness is in student performance, said de los Reyes. “You see the improvement of the students, the development of complex ideas, and the depth of engagement. It’s very obvious and clear.”

For Guilford, the program isn’t only a learning tool in the classroom, but also an example of “great pioneering” in education.

“It’s going to be around for quite a while.”