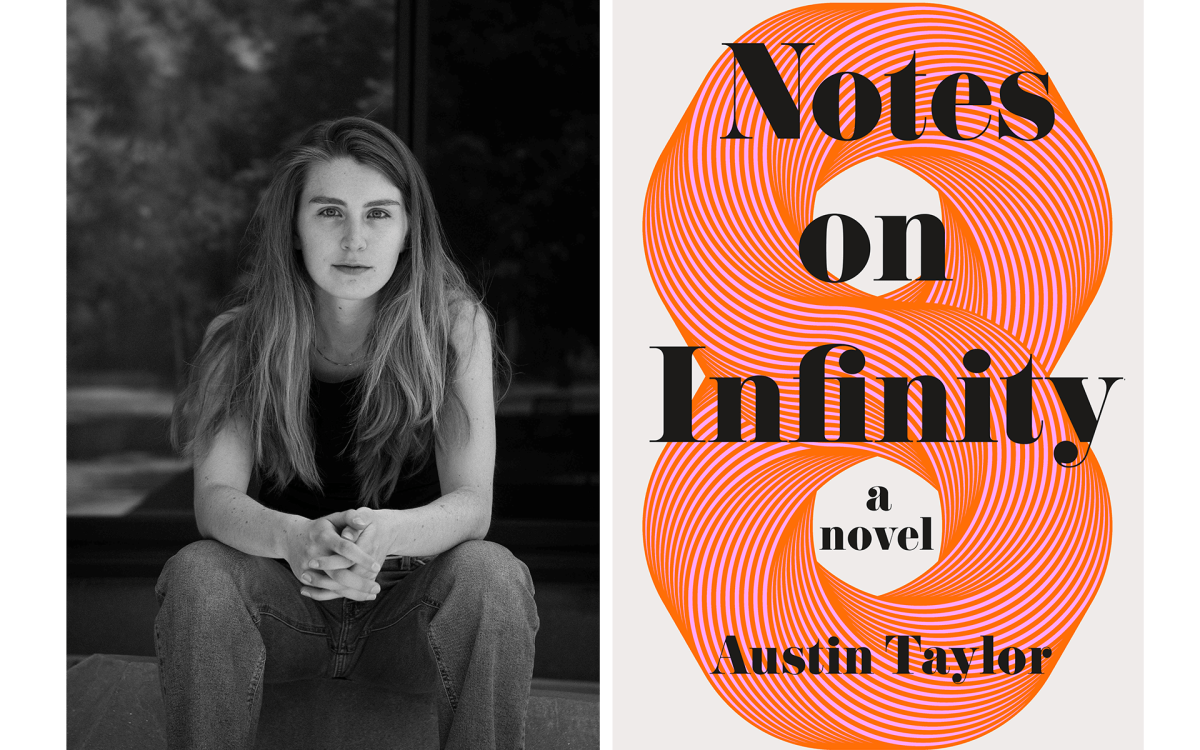

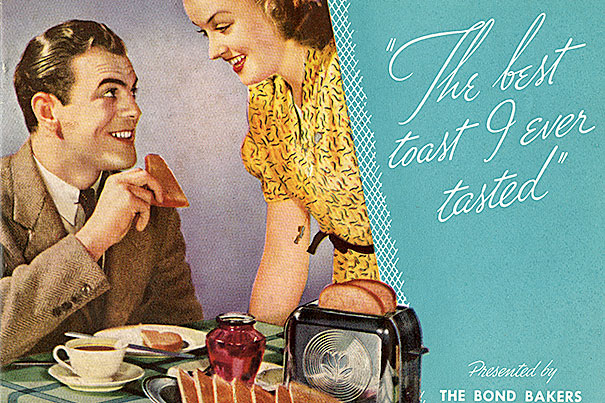

Cultural stereotypes around food remain, according to Marilyn Morgan, the professor behind the Harvard Summer School course “Gender, Food and Culture in American History.” An early look: “The best toast I ever tasted,” 1939 (photo 1); “How to enjoy your 1951 General Electric refrigerator-food freezer combination,” (photo 2); students participating in a cooking class, ca. 1929-34 (photo 3).

Culinary Pamphlet collection, Hilda Worthington Smith Papers/Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe

Food, gender, culture

Course shows depth, intensity of Summer School offerings

Harvard Summer School is old, since it opened in 1871 as the first university summer studies program in the nation. But it’s also young, since nearly a quarter of its 6,000 students this summer were teenagers in its Secondary School Program.

The Summer School also extends well beyond Harvard Yard. There were 28 overseas programs, including in China, France, Israel, and Kenya. (One recent student summed up international study by saying: “We had to take off our American goggles.”)

And the seven-week summer program is big, with more than 300 courses. From late June to early August, students studied the Vietnam War, fairy tales, the anthropology of childhood, utopia, Bob Dylan (a seminar), the odes of Horace, astrobiology, video editing, the Harlem Renaissance, environmental crises, the early plays of Shakespeare, and digital storytelling. Students also did writing involving journalism, novels, short stories, travel, and food.

Food was the star of one course, SWGS S-1155, better known as “Gender, Food and Culture in American History.” The professor was Marilyn Morgan, a manuscripts cataloger at the Schlesinger Library who has a Ph.D. in American history. The course’s guiding idea is that food isn’t just something to eat. It’s a shared cultural experience that on close examination reveals a lot about gender, race, and class.

By the end, it taught a sobering lesson, at least regarding gender in advertising. “Not much has changed,” said Morgan. Food roles are as gendered now as they were in the America of nearly 200 years ago. “I still am astonished over how clueless people are to these sexist ads and norms in society,” wrote student Elizabeth Greif in an email, adding italics to the next sentence: “This stuff is still happening today!”

When the students read snippets of food writing from 1841, 1898, and the present, Morgan said not one could identify the era of a single text. Women are still largely perceived as the ones responsible for buying, preparing, and serving food, she said — as well as the ones to blame if things go wrong.

Grinding, gritty, rewarding

The 13 students in the class covered a lot of demographic ground, typical of Harvard Summer School. Four were from high school (including Greif, a rising senior from desert-bound Quartz Hill, Calif.); two came from overseas; and many of the others were Southerners. They joined to study print and television ads, 19th-century treatises on domestic skills, vintage cookbooks, and decades of scholarship on the intersection of what we eat and who we are.

The coursework offered a lesson in what the Summer School means: seven weeks of grinding, gritty — but rarified and rewarding — work. “Admittedly there was a lot of reading,” Alabaman Mia Tankersley ’14 said in an email. “But honestly, having to reflect on the evolution of macaroni in the United States or soul food didn’t feel like work.”

Another student, Nadine Mannering, who arrived this summer with a master’s degree from her native Australia, said the workload was “fairly intense,” but it was the first time she had been in college without having to work at a paying job, too. “I relished the opportunity to actually focus on my studies first.”

Morgan’s students averaged 150 pages of reading per class, 300 pages a week. Using new software, they illustrated timelines that could eat up half a day. And their weekly writing assignments, brightened and honed, appeared on a class blog that remains open and active. “They learned,” said Morgan, that “the real challenge was how to write effectively in that short a space.”

The writing is tight, and the timelines enlightening. (In the one on canned food, we learn that the billionth can of Spam was produced in 1959. In another, we get this sweet bit: 400 million M&Ms are made every day in the United States.) The texts also use vintage ads as points of argument. A 1950s TV pitch for instant coffee contains a minute of husband-wife food dynamics that today would make anyone queasy. (Instant coffee got its first popularity bump with men during World War II, said Greif, who studied it for her final project. But advertisements often “included women serving a cup to men,” she said, “despite how easy it would have been for the man to make the coffee himself.”)

Using primary sources

The students’ final research papers required primary sources, in this case, mostly from Schlesinger. The library, part of the Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Study, houses the richest American women’s history collections, including the papers of chef Julia Child and early feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

Gilman, whose “Women and Economics” (1898) was on the course reading list, wanted women to change their house-centric identities. “A house does not need a wife any more than it needs a husband,” she wrote, a sentiment that put her at odds with her anti-suffragist aunt, Catharine Beecher, whose 1845 “Treatise on Domestic Economy” was also required reading. Aunt and niece were opposing bookends in the 19th-century debate over the role of women, an uneasy tension that still exists today. “I’m a feminist who loves to bake,” said Tankersley, “and I constantly think about what that means and why I’m conflicted about it.”

By the end of class, most of the final papers used foods — rather than personalities — as a cultural lens. Many were previewed in the student timelines, including looks at food preservation, M&Ms, peanut butter, wedding cake, pineapple (marketed as “glam” and exotic in the 1950s), artificial sweeteners, and Cream of Wheat. The last product was part of a leitmotif in class, what Morgan called an “archetype of using subservient Others” to sell a product in the 20th century.

For Cream of Wheat, at first, that “Other” was Rastus, a black man in a chef’s hat and white coat. For other products, it was Aunt Jemima or Uncle Ben. “There were too many surprises to count,” said Tankersley of the course, including the true story of Aunt Jemima. She was Nancy Green, a former slave hired in 1893 to promote pancake mix at the Chicago World’s Fair.

The female hand in the universe of preparing food gets more subtle as advertising enters the era of second-wave feminism. Gone are the women in dresses pouring coffee or fussing over cakes in the daytime. But women are still in the kitchen, as in the TV ad Mannering used in her study of Tupperware parties — marketing artifacts of the 1950s that today still limit the hostess-saleswoman to commissions only. “Though we always think we’ve come so far, there (are) always, always things that need to be worked on,” Mannering said. “We should never (assume) everyone’s being treated equally and fairly.”

Meanwhile, men remain just as stuck in their food roles of 50 years ago, mostly as guilt-free consumers of high-calorie snacks. The final flowering of that role might be the “Get Some Nuts” TV ads for Snickers, a “man candy” chock full of protein and energy. In food ads, women aspire to low calories, satisfaction, and even female agency — from yogurt, say, a product still largely pitched to one gender. The marketing subtext often even co-opts a standard second-wave feminist joke: Who needs men? (When you have yogurt, at least.)

Summer demographics

The same joke, in its own way, was repeated in the course. Of 13 students, only one was a man, a fact that Morgan attributed to having “gender” in the course title.

But the demographics in this class were in other ways typical of the Summer School. The four high school students made up about a quarter of the class, the same proportion as in the whole program. There were two foreign students in the class, from Taiwan and Australia. In the School at large, the percentage of international students is higher, 37 percent last year. Mannering, who works for a bank in Melbourne, took three months off to tour the United States, but started her visit with the course. “I was flattered,” said Morgan.

“I wanted a base in the States,” said Mannering, “so I chose summer school. Harvard was an obvious choice as it’s — in my mind — the best university in the world. Doing summer school allowed me to get to know Cambridge and Boston, and have a temporary ‘home’ in America.”

The undergraduates in the course were also expressive of a geographical range — New York, Virginia, Alabama — that that is typical for Harvard year-round.

Something else about Morgan’s students was likely true of everyone at the Summer School. “Most were exploring something about themselves,” she said. That included a native Southerner (now a Boston-area lawyer) who did a final paper on North Carolina barbeque, and was shocked to discover that most such operations are run by men. (That matched Morgan’s general take on food prep: Women cook, men grill.)

There’s yet another way that the course was like a lot of others at the Summer School: There was fun, too. Students could join the gym, play in a pops band or orchestra, row on the Charles River, volunteer at nonprofits, take sponsored tours around Boston, or venture out to Cape Cod or Tanglewood or even as far as Rhode Island or Maine.

“Boston is just a T stop away,” said Greif, the Californian teenager. “History and more history await to be explored, and I want to explore everything.”

Morgan’s students took time on a July Saturday to visit the outdoor market at Haymarket and the food-intensive Feast of St. Joseph street festival in Boston’s North End. The trip included a look at the site of the landmark Boston Cooking School (1879-1902), where Fannie Farmer, of cookbook fame, studied and taught.

What inspired the course? For one, Morgan read the Works Progress Administration slave narratives as a graduate student, with an eye to how former slaves would “use food as a means of exerting power in a situation in which they were powerless.” It was slavery, and the legacy of African foods and spices, that made Southern cooking what it is, she said. Food historian Frederick Douglass Opie, author of “Hog and Hominy: Soul Food from Africa to America” (2008) was a guest lecturer. He was a 2012-2013 fellow at the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute.

Morgan was also inspired by her work at Schlesinger, which last year included cataloging the papers of Jean Wade Rindlaub, a New York advertising executive who, among other things, created ads for cake mixes and other convenience foods. Her secret involved direct emotional appeals to women. Her papers are a window into the machinery of marketing food.

Mannering was struck by how different advertising is in Australia. “There is a lot of ‘mother-guilt’ in American advertising,” she said, “brands telling women that their product is healthy and best for their child in an attempt to create insecurities and secure the demographic.”

More than one student came away from Morgan’s class with a critical eye on sugar, which Tankersley said food companies are increasingly adding to make up for using less fat. “I could go on and on about how dangerous it is for us, but let’s just say that after that class I was prepared to swear off all sugar (aside from fruit),” she wrote. “Then I made a beeline for a cup of coffee Oreo ice cream. So it’s a work in progress.”