Using a new, stem cell-based, drug-screening technology developed by Professor Lee Rubin at the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, researchers have found a compound that is more effective in protecting the neurons killed in ALS than the two drugs that failed in human clinical trials.

File photo by B. D. Colen/Harvard Staff

Big boost in drug discovery

New use for stem cells identifies a promising way to target ALS

Using a new, stem cell-based, drug-screening technology that could reinvent and greatly reduce the cost of developing pharmaceuticals, researchers at the Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) have found a compound that is more effective in protecting the neurons killed in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) than are two drugs that failed in human clinical trials after large sums were invested in them.

The new screening technique developed by Lee Rubin, a member of HSCI’s executive committee and a professor in Harvard’s Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology (SCRB), had predicted that the two drugs that eventually failed in the third and final stage of human testing would do just that.

“It’s a deep, dark secret of drug discovery that very few drugs have been tested on human-diseased cells before being tested in a live person,” said Rubin, who heads HSCI’s program in translational medicine. “We were interested in the notion that we can use stem cells to correct that situation.”

Rubin’s model is built on an earlier proof of concept developed by HSCI principal faculty member Kevin Eggan, who demonstrated that it was possible to move a neuron-based disease into a laboratory dish using stem cells carrying the genes of patients with the disease.

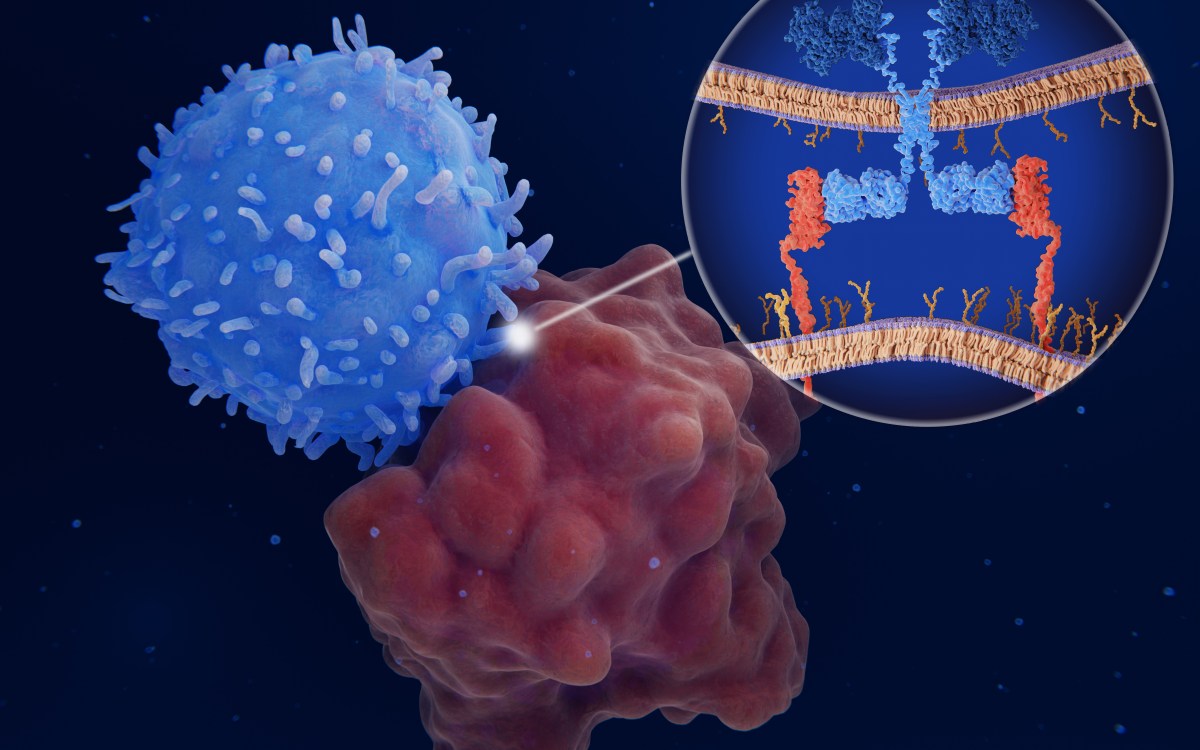

In a paper published April 18 in the journal Cell Stem Cell, Rubin laid out how he and his colleagues applied their new method of stem cell-based drug discovery to ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. The illness is associated with the progressive death of motor neurons, which pass information between the brain and the muscles. As cells die, people with ALS experience weakness in their limbs, followed by rapid paralysis and respiratory failure. The disease typically strikes later in life. Ten percent of cases are genetically predisposed, but for most patients there is no known trigger.

Rubin’s lab began by studying the disease in mice, growing billions of motor neurons from mouse embryonic stem cells, half normal and half with a genetic mutation known to cause ALS. Investigators starved the cells of nutrients and then screened 5,000 druglike molecules to find any that would keep the motor neurons alive.

Several hits were identified, but the molecule that best prolonged the life of both normal and ALS motor neurons was kenpaullone, previously known for blocking the action of an enzyme (GSK-3) that switches on and off several cellular processes, including cell growth and death. “Shockingly, this molecule keeps cells alive better than the standard culture medium that everybody keeps motor neurons in,” Rubin said.

Kenpaullone proved effective in several follow-up experiments that put mouse motor neurons in situations of certain death. Neuron survival increased in the presence of the molecule whether the cells were programmed to die or were placed in a toxic environment.

After further investigation, Rubin’s lab discovered that kenpaullone’s potency came from its ability also to inhibit HGK, an enzyme that sets off a chain of reactions that leads to motor neuron death. This enzyme was not previously known to be important in motor neurons or associated with ALS, marking the discovery of a new drug target for the disease.

“I think that stem cell screens will discover new compounds that have never been discovered before by other methods,” Rubin said. “I’m excited to think that someday one of them might actually be good enough to go into the clinic.”

To find out if kenpaullone worked in diseased human cells, Rubin’s lab exposed patient motor neurons and motor neurons grown from human embryonic stem cells to the molecule, as well as two drugs that did well in mice but failed in phase III human clinical trials for ALS. Once again, kenpaullone increased the rate of neuron survival, while one drug saw little response, and the other drug failed to keep any cells alive.

According to Rubin, before kenpaullone could be used as a drug, it would need a substantial molecular makeover to make it better able to target cells and find its way into the spinal cord so it can access motor neurons.

“This is kind of a proof of principle on the do-ability of the whole thing,” he said. “I think it’s possible to use this method to discover new drug targets and to prevalidate compounds on real human disease cells before putting them in the clinic.”

Rubin’s next steps will be to continue searching for better druglike compounds that can inhibit HGK and thus enhance motor neuron survival. He believes that the new information that comes out of this research will be useful to academia and the pharmaceutical industry.

“These kinds of exploratory screens are hard to fund, so being part of the HSCI” — which provided some of the funding — “has been absolutely essential,” Rubin said.

Those working on the finding included Clifford Woolf, HSCI nervous system diseases program leader, and postdoctoral students Brian Wainger, Miranda Yang, Shailesh Gupta, Kevin Kim, Berit Powers, and Antonio Cerqueira.

The work was also funded by the New York Stem Cell Foundation and the ALS Association.