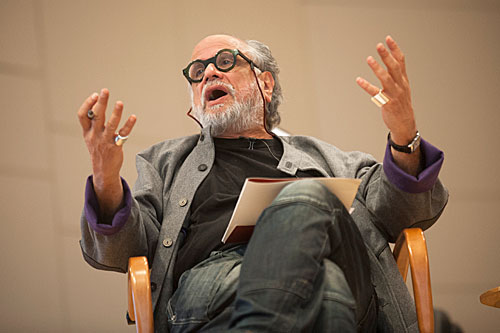

“What you just heard, in some way, reflects what cultural citizenship is,” said cellist Yo-Yo Ma (center) before participating in a discussion on the topic, which was moderated by Diana Sorensen.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

The quest for common ground

Panel explores factors that promote ‘cultural citizenship’

Asked to define the concept of “cultural citizenship” at a panel convened to explore that question, Yo-Yo Ma ’76, cellist and artistic director of the Silk Road Ensemble, pointed to an unexpected answer: guest pianist Tania Rivers-Moore ’15.

Rivers-Moore had met with Ma and two other ensemble members for the first time that morning to rehearse a piece by Brahms, which the quartet performed for the symposium’s audience right before the panel began.

“What you just heard, in some way, reflects what cultural citizenship is,” Ma said. “She was given this piece of music just a week ago, but here’s the thing. She was ready to jump in, and we were ready to jump in also. So part of cultural citizenship is that readiness, starting that leap from the inside, and combining with other forces to make it work.”

Moderated by Diana Sorensen, dean of arts and humanities and the James F. Rothenberg Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and professor of comparative literature, the panel discussed topics ranging from migration trends and exclusionism to translation and individual openness to cultivating cultural citizenship.

Panelist Homi K. Bhabha, Anne F. Rothenberg Professor of the Humanities and director of the Mahindra Humanities Center, which co-sponsored the event with the Silk Road Project, said that culture becomes “the voice of expression” for many migrating communities because they lack political representation or public recognition.

“Forms of cultural citizenship at the level of aesthetic and artistic expression require, in the broadest sense, a simple means of translation,” Bhabha said. “To try and understand the culture, the music, the art of another period, to try to translate across time, space, history, and across geography… that is extraordinarily important in the area of cultural citizenship.”

Jacqueline Bhabha, director of the Harvard University Committee on Human Rights Studies, director of research at the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, and wife of fellow panelist Homi K. Bhabha, noted that she often works from “the dark side of citizenship,” where people experience citizenship as exclusion rather than inclusion. Having worked extensively with members of the Roma community in Europe, whose presence dates to the seventh century, Bhabha said that culture helps to bridge that void of exclusion.

“Despite these generations and centuries of life in the heart of civilization, if you like, the Roma are still extraordinarily discriminated against,” she said. “So it’s remarkable that this community has this tremendous, vibrant tradition, particularly in music.

“That is, in a way, the Roma tradition: not language, not religion, not nationality, but this very strong sense of cultural community. Music is one of the great attributes of cultural citizenship.”

Panelist Colin Jacobsen, violinist and composer with the ensemble, said the fluid nature and shared language of music contributes to cultural citizenship just about every time the group practices.

“In order to play with someone else, you have to have a shared common ground on which to stand,” he said. “Each one of us … comes from a particular tradition, but there’s also a common sense of curiosity about what we don’t know, and the desire to reach out and hopefully incorporate that.

“It doesn’t mean you have to learn everything about another tradition. But you need a sense of courage to leap into the unknown. And in that moment, in that encounter, there’s a desire to not hold on to only what you know, but to try and fully absorb what is in front of you in that moment … and hopefully you then learn and grow as well.”

Panelist Cristina Pato, founder and director of Galician Connection and a founding member of the Silk Road Ensemble Leadership Council, suggested that the boundaries of culture and music may be much more shared and permeable than we believe. She recently discovered that the suona, a traditional Chinese instrument, makes the same sound as her instrument, the gaita, a traditional instrument from Galacia, Asturias, and northern Portugal.

“It’s the same sound. Everything is so interconnected,” she said emphatically. “It’s all connected, so much more than we think.”