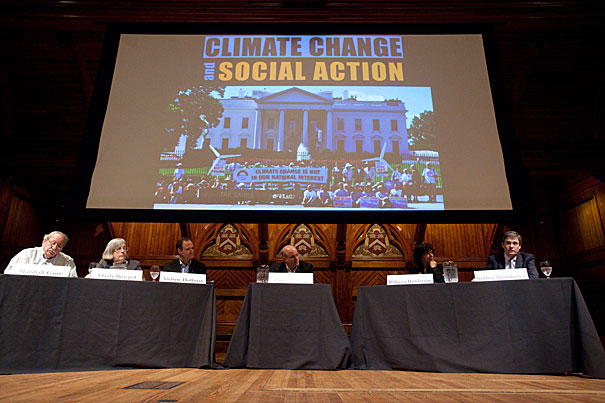

Harvard University Center for the Environment symposium on social action and climate change, at Sanders Theater. Marshall Ganz, Theda Skocpol, Andrew Hoffman, Dan Schrag, Rebecca Henderson, and Stephen Ansolabehere. Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

A groundswell on climate change

Social action, rather than government edict, may break policy logjam, panel says

If you seek change — as today’s climate change activists do — you can’t shrink from conflict, because the two go hand-in-hand in a democracy, according to a Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) authority on social organizing.

Marshall Ganz, an HKS senior lecturer in public policy, drew on his decades of experience in the Civil Rights Movement and as a community organizer to offer lessons for those seeking change.

“The idea that democracy is about consensus, I don’t know where that idea came from,” Ganz said. “Democracy is about contention, about constructive contention.”

Ganz was among panelists considering social activism on climate change during “Climate Change and Social Action,” a discussion Monday at Sanders Theatre sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment.

Other panelists included Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology; Government Professor Stephen Ansolabehere; McArthur University Professor Rebecca Henderson; and Andrew Hoffman of the University of Michigan. The moderator was Daniel Schrag, director of the Center for the Environment, Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology, and professor of environmental science and engineering. Harvard President Drew Faust offered comments at the program’s end.

The panelists gave the climate change movement low marks compared with major social movements of the past, such as those that ended slavery, fostered civil rights, fought tobacco use, and abolished apartheid.

Skocpol, who recently completed a report on the failure of environmental cap-and-trade legislation during President Barack Obama’s first term, said there is a large gap between Washington-based environmental groups that focus their efforts on legal and regulatory change and grassroots organizers seeking to mobilize the population on this issue.

The cap-and-trade legislation failed, Skocpol said, in part because it was drafted as a high-level agreement between top players on the issue whose lead Congress was expected to follow. They didn’t take into account how polarizing the issue had become for legislators. Any future efforts, she said, should include significant grassroots organizing in every state and congressional district.

“I don’t think you’ll do it with an inside game. You need the involvement of citizens,” Skocpol said.

Hoffman equated the reform needed for meaningful climate action to the abolition of slavery because such areas require fundamental changes to existing economic models. With slave labor providing the wealth of the overlord society, ending the institution — aside from its moral aspects — represented an enormous economic transformation.

Similarly, the availability of cheap fossil fuels is the foundation on which the global economy is built, so shifting to other energy sources will be neither quick nor easy, he said. It took England a century to abolish slavery. In the United States, it took a civil war.

Ansolabehere, who has conducted extensive polling on the environment, said that people are concerned about climate change. But it’s still not even their top environmental issue, since that title goes to clean water. People think something should be done about climate change, but their support for reform plummets when they learn that their monthly electricity bills will rise.

“People are not willing to pay extra to address this issue,” Ansolabehere said.

If a constituency isn’t strong, it is up to the social organizers to build it, Ganz said, which is a role that young people and universities can play. They need to identify who is interested in this issue and who is already out there working on it, he said. “That’s the challenge of movement building, and where young people and universities can play a role,” Ganz said, adding that young people have to ask where they have access and influence to begin making change.

Panelists touched on some Harvard students’ calls for the University endowment to divest from the stocks of fossil fuel companies, with Hoffman saying there is a similar movement at the University of Michigan. Although some portfolio managers disagree, Henderson said that environmentally friendly portfolios have shown comparable rates of return. Hoffman added that there are other ways shareholders can influence the issue besides divesting, by exercising shareholder power to convince large fossil fuel companies to take more environmentally friendly action, like refusing government subsidies, using fossil fuel profits for renewable research, and halting government lobbying.

Even though climate change has yet to galvanize enough broad public support to prompt federal action, several panelists suggested that this is already a period of change. Schrag traced a shifting of public opinion on the issue to Hurricane Sandy, which devastated the New York and New Jersey coastlines and which New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg suggested was linked to climate change during his subsequent endorsement of Obama for re-election.

“Sandy suddenly evoked a connection to climate change in people’s minds,” Schrag said.

Other panelists said some businesses are ready to change. They recognize that carbon releases into the atmosphere will have to be regulated, but they need government to take the lead by levying a price on carbon emissions. That will let them know what a new economic playing field looks like and identify opportunities within it.

“There are a huge number of business opportunities here. There are business people who want to take the lead,” Henderson said.

Hoffman suggested that this may be something of a renaissance now, citing the shift of auto vehicle fleets to hybrid and electric technologies, the movement by California to regulate carbon emissions even absent federal action, the coming need to rebuild the aging electricity transmission grid, and a major shift from coal toward cleaner — though still carbon-emitting — natural gas, made abundant by new extraction technologies.

“The funny thing about a renaissance is you don’t see it until it’s done. All you can see is the pain” leading toward it, Hoffman said.

In her closing comments, Faust said the session was especially thought-provoking for someone who had made a career of studying the American South and the Civil War, and who was a college student herself during the civil rights era.

“I look forward to more conversations, more arguments, more vibrant democracy, and to mobilizing universities in ways that enable us to support the very best of human life and the best for the planet on which we live,” Faust said.