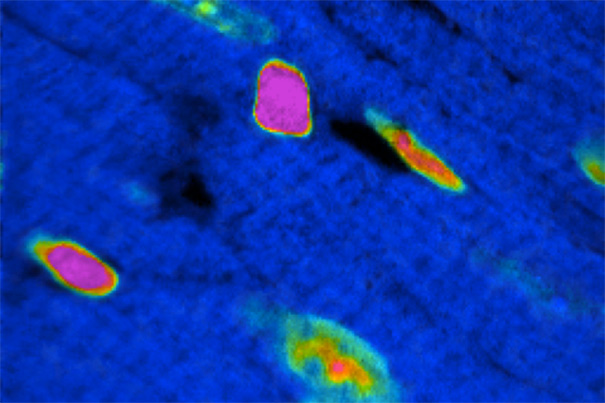

A sophisticated imaging system, multi-isotope imaging mass spectrometry (MIMS), demonstrates cell division in the adult mammalian heart. Researchers were surprised to find that new heart muscle cells primarily arose from existing heart muscle cells, rather than stem cells.

Image courtesy of Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Birth of new cardiac cells

Advanced technology yields some surprises

Recent research has shown that there are new cells that develop in the heart, but how these cardiac cells are born and how frequently they are generated remains unclear.

In a study from Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), researchers used a novel method to identify the new heart cells and describe their origins.

The research was published today in Nature.

“The question about how often cardiac cells are born has been extremely difficult to answer because there was a need for new techniques to help us understand this process,” said Harvard Medical School Professor of Medicine Richard T. Lee, the senior author of the paper and a researcher in the Cardiovascular Division at BWH.

“We are especially excited about our findings because of the novel way in which we were able to show new heart cells, using multi-isotope imaging mass spectrometry (MIMS),” Lee continued. “Our collaborator, [HMS Associate Professor of Medicine] Claude Lechene, had developed this technology, and as a team we harnessed this for the cardiac regeneration question. These data present one piece of the puzzle when it comes to the discussion around the generation of new cardiac cells.”

The team of BWH researchers marked existing cardiac cells genetically to cause them to express a green fluorescent protein. Then they used MIMS to examine the development of new heart muscle cells, called cardiomyocytes, in a preclinical model over a period of months. Researchers were surprised to find that new heart muscle cells primarily arose from existing heart muscle cells, rather than stem cells. Even in the setting of a heart attack, when stem cells are thought to be activated, most new heart cells were born from pre-existing heart cells.

“Our data show that adult cardiomyocytes are primarily responsible for the generation of new cardiomyocytes and that, as we age, we lose some capacity to form new heart cells,” said Lee. “This means that we are losing our potential to rebuild the heart in the latter half of life, just when most heart disease hits us. If we can unravel why this occurs, we may be able to unleash some heart regeneration potential.”

This research was funded through grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, Future Leaders in Cardiovascular Medicine, the Watkins Cardiovascular Leadership Award, and the Ellison Medical Foundation.