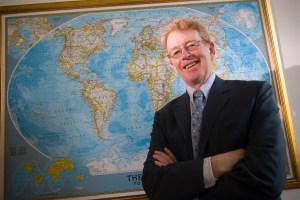

Transplant pioneer dies at 93

Joseph Murray conducted first successful organ transplant

Joseph E. Murray, emeritus professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School, whose many breakthroughs included the first successful kidney transplant, died Nov. 26, after suffering a hemorrhagic stroke at his Wellesley, Mass., home on Thanksgiving. He was 93.

Murray shared the 1990 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine with E. Donnall Thomas, M.D. ’46, for conducting the world’s first successful organ transplant in 1954.

At the time, relatively little was known about the intricate workings of the human immune system, but it was clear that a patient’s immune response posed a formidable barrier to transplantation, a problem Murray confronted while serving as a plastic surgeon during World War II.

Murray joined the U.S. Army Medical Corps after graduating from Harvard Medical School in 1943. Many of his patients were soldiers with burn injuries, some so severe that the patient didn’t have enough undamaged skin for a graft. When Murray tried grafts using another person’s skin, he would watch with frustration as the patient’s body slowly rejected the graft.

With immunosuppression in its infancy, Murray focused instead on the possibility of transplants from a patient’s closely related donor. By the early 1950s, he had achieved significant success with transplants between animals. Based on that progress, and the progress that others were making in the field, he proposed that a patient might accept an organ transplanted from an identical twin.

In 1954, Richard Herrick, a 23-year-old man with severe kidney disease, was referred to Murray. Although there was no medical cure, Murray told Herrick he did have cause for hope. He had an identical twin brother, Ronald, with healthy kidneys. No one had ever been asked to donate a healthy organ, but Ronald was quick to agree.

Knowing that they were taking an extraordinary course of action, everyone involved agreed to keep word of the surgery under wraps. The story did get out, however, leaked from an unexpected source. To confirm that the twins were indeed identical, Murray had arranged for the brothers to be fingerprinted at a Boston police station. An enterprising newspaper reporter on the police beat got word of the unusual “booking,” and the lid was off.

The surgery was performed Dec. 23, 1954, at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. Both brothers fully recovered from the groundbreaking operation. Richard later married one of his nurses, with whom he had two children before his death, of complications of kidney disease, in 1963. Ronald died in 2010, at age 79.

Murray went on to perform the first transplant using a kidney from a nonidentical twin in 1959 and the first transplant from a deceased donor in 1962. The age of organ transplantation had arrived.

Murray continued to lead the way in transplant surgery, serving as head of the program at the Brigham until 1971. At that point, he later told an interviewer from the Journal of the American Medical Association, he decided to focus on his “true calling”: plastic surgery. “At heart, I’m a reconstructive surgeon.” That prompted his friend and colleague Francis Moore to note, “Joe’s the only guy who ever won a Nobel Prize for pursuing a hobby.”

As head of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Children’s Hospital Boston, Murray was a leader in craniofacial reconstruction. He introduced to the United States a procedure that corrected head deformities by resectioning and moving forward the bones of the head and face. In 1986, he suffered a stroke, and, while he was quick to recover and cleared for returning to the operating room, Murray chose to retire.

“I had 48 years of surgery under my belt and I decided to just enjoy other aspects of my life,” he said.

Those aspects included an active retirement with Virginia “Bobby” Link, whom he married in 1945, their six children, and 18 grandchildren. Murray published an autobiography, “Surgery of the Soul,” in 2001. On several occasions, he reunited with Ronald Herrick and the extended Herrick family, including Richard’s widow and children.