Over two days, Harvard hosted a cohort of scholars in medieval sermon studies, a pursuit that helps illuminate the social and intellectual currents of the Middle Ages. French medievalist André Vauchez (above), a scholar of sermon studies, delivered the keynote. Vauchez is at work on a biography of St. Francis of Assisi, who took sermons to the streets and used his simple lifestyle itself as a moral exemplar. “Some people are more moved by example than by reason,” Vauchez told his audience.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Speaking volumes

Specialists in medieval sermon studies talk shop at Harvard

Three experts in medieval sermon studies walk into a Harvard Square bar. One of them says …

But this is no joke. Last week, the world’s authorities on centuries-old catechetical discourse gathered at Harvard for “Preaching the Saints,” a conference on the sermons, art, and music of medieval and early modern Europe. If any of them walked into a nearby bar, surely it was to discuss J.B. Schneyer’s “Repertorium der lateinischen Sermones des Mittelalters.”

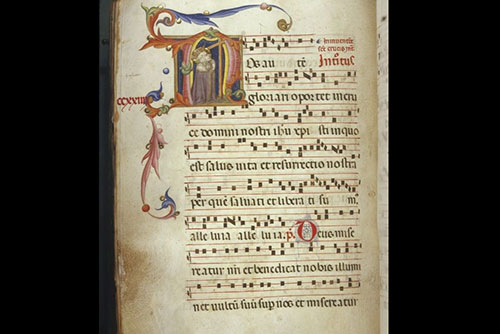

This 11-volume catalog of 100,000 sermons in Latin — a feat of scholarship from 1969 to 1990 — helped inspire the idea of medieval sermon studies, which in turn has helped uncover the social and intellectual currents of the Middle Ages. Until Schneyer, scholars were hobbled by how few sermons had been edited, translated, and prepared for study. Contemporary cataloging projects, like SERMO, continue his work. And researchers still depend on traditional manuscript collections, like those at Harvard’s Houghton Library.

Today, there are approximately 60 sermon studies experts in the world, said Harvard Professor of English Nicholas Watson — “It’s a genuine specialization,” he said — and another 500 medievalists, like himself, who occasionally use sermons in their scholarship.

One of the 60 is Harvard’s Beverly Mayne Kienzle, the John H. Morison Professor of the Practice in Latin and Romance Languages at Harvard Divinity School.

She is past president of the International Medieval Sermon Studies Society and has mentored graduate students for 25 years. A fierce believer in primary sources, Kienzle is a champion of Houghton’s medieval sermon collection, the subject of a companion exhibition both online and in the Amy Lowell Room. To her, sermons are a pathway to insights into monasticism, dissent, and the lives of women in the Middle Ages.

Also among the conference experts was French medievalist André Vauchez, a scholar of sermon studies who delivered the Sept. 21 keynote in the Barker Center’s Thompson Room. His landmark book, “Sainthood in the Later Middle Ages,” first appeared in English in 1987.

Vauchez is at work on a biography of St. Francis of Assisi, a 13th-century Italian monk venerated today for his embrace of poverty and love for animals. He was one of the mendicant — begging — preachers who took sermons to the streets, and who used his simple lifestyle itself as a moral exemplar. “Some people are more moved by example than by reason,” said Vauchez.

Mendicant preachers not only preached by example, they often embellished their sermons with rhymes, songs, animal analogies, and examples from real life. An opposing idea held that sermons should be more arguments than stories — phrase-by-phrase expositions on Scripture known in the day as lectio continua. The same stylistic tension still exists in written discourse today.

Before printing, sermons

The work of Vauchez, Kienzle, and others is not so specialized that it has no meaning for the rest of us. After all, said Watson, it was the ecclesiastical system behind sermons “that invented the idea [that] there was a universal body of knowledge” and that led the way to modern universities. Sermons were the dominant literary form in the Middle Ages. They bridged the emerging power of the written word and what was, 900 years ago, the predominance of the spoken.

Theological and moral messages delivered centuries ago also help today’s scholars investigate the social content of the Middle Ages, including politics, trade, marriage, the lives of women, and, of course, the business of religious devotion. Some sermons, delivered to monks and nuns in Latin, were meant to encourage meditation and inward thought. Others, delivered in the vernacular, were meant to instruct sometimes unruly lay audiences about Christian teachings and to refute paganism. One ninth-century preacher exhorted his listeners to stop howling at the moon.

Though commonly designed to explain Scripture and to urge moral behavior, sermons sometimes had more homely missions, like praying for rain. And a few had covertly political missions. In the name of doing penance for sins, for instance, some preachers exhorted listeners to join in crusades.

Before the printing press, knowledge was disseminated through oral traditions. In the public sphere that meant sermons. These discourses from the pulpit were the Internet and the mainstream press and the propaganda machine of the Middle Ages.

Airwaves of the Middle Ages

At the same time, sermons of nearly a millennium ago prompted a very modern question: Who has the right to speak? Vying with priests for the right to preach were lay people, lawyers, kings, and public officials. In a bit of recurrent culture shock, even women demanded the right to preach sermons.

Most of all, the prospect of lay preaching “was an anxiety for the Church,” wrote Carolyn Muessig in a study of medieval preaching and society. (The University of Bristol scholar delivered the first paper at the Harvard conference.) The concern, she wrote, was the Vatican’s desire to protect people from heresy and “to preserve a clerical monopoly on learning.”

The debate over who owned the medieval airwaves went on for hundreds of years. As late as the 14th century, one critic still held that the Vatican had the final say. “No lay person can preach without authorization,” wrote Robert de Basevorn, “and no woman ever.”

There were exceptions to the gender rule. Most famous was poet, visionary, herbalist, and polymath Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th-century Benedictine nun. Muessig co-edited a 2007 edition of her homilies — sermons — on the Gospels, “Expositiones evangeliorum,” with Harvard’s Kienzle.

The two days of “Preaching the Saints” were crowded: 12 lectures, a keynote address, and posters of work by six of Kienzle’s graduate students — an unusual strategy during conferences in the humanities, said Watson. (The six students — James Blasina, Jenny C. Bledsoe, Jennifer De La Guardia, Craig Tichelkamp, Katherine Wrisley Shelby, and John Zaleski — also helped write and arrange the Houghton exhibit.)

The conference included two presentations on St. Clare of Assisi, a “superheroine” of the 13th century and — in saintly legend — beyond, said Watson. She founded the Order of Poor Ladies (the Poor Clares), a satellite order of the Franciscans that was devoted to prayer, silence, and poverty. In 1958, Clare was named the patron saint of television. On days she was too sick to attend Mass, the story goes, Clare had the ability to watch and listen by looking at a wall in her room.

In a summation, Watson praised the assembled scholars for using sermons to look beyond text and into the real life of the Middle Ages. “Not what it was like,” he said of medieval society, “but what it felt like, what it was like imaginatively.” But Watson also hoped that sermon studies might go beyond a desire to describe a vanished time and embrace as well what is “doctrinal and the intellectual.”