“Unfortunately, there is very little written in English and other Western languages about Chinese Islamic calligraphy, making the visit of Haji Noor Deen and the exhibition very special,” said Professor Ali Asani, director of the Alwaleed Islamic Studies Program and chair of the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations.

Photos by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Sweeping gestures, divine power

Examining ‘Arabic Islamic Calligraphy in the Chinese Tradition’

Master of calligraphy Haji Noor Deen wowed Harvard in April during a demonstration of his singular Arabic Islamic calligraphy in the Chinese style. Now his work is on display in the CGIS South building in an exhibit titled “Arabic Islamic Calligraphy in the Chinese Tradition: Works by Master Haji Noor Deen.” The exhibit is sponsored by the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Islamic Studies Program and the Harvard University Asia Center.

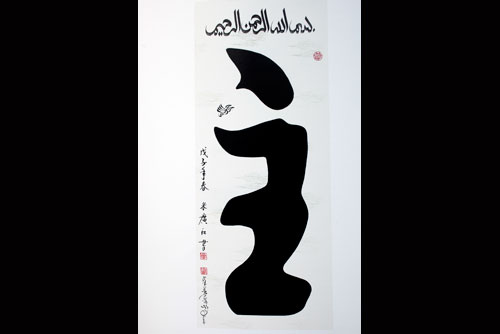

Knowledge of Arabic and Chinese may help the viewer access added joys — tilt your head to the left and a Chinese character for “peace” gives way to a cursive Arabic salaam — but even those who do not read either language can appreciate the beauty of Noor Deen’s work.

“His calligraphy has a boldness about it, and at the same time a gentleness to it, that really conveys the sense of divine power and at the same time, beauty, grace, and subtlety,” said Elizabeth Lee-Hood, a Ph.D. student who studies Islamic devotion. “There is a sweep of the brush strokes that combines simplicity with a sense of encompassing scope.”

Noor Deen uses a soft brush to make long, evocative strokes that echo the sentiment of the passages represented.

“In the phrases that are actually prayers calling out to God — as in ‘O! Gracious One!’ — you see an upward sweep as if an upward reach of the human heart to God,” said Lee-Hood.

Noor Deen’s free and fluid style is evident in his diverse representations of the Bismillah, a phrase that prefaces many passages of the Quran and precedes many daily activities for Muslims, and a popular calligraphic motif. In some pieces, the artist writes the phrase with a single brush stroke, as the devotee utters it with a single breath. In another piece the phrase hovers over the word “God” in the shape of a pictogram of a man kneeling in prayer.

Although Islam has a long history in China, few Westerners know much of the community or its rich artistic tradition.

“Unfortunately, there is very little written in English and other Western languages about Chinese Islamic calligraphy, making the visit of Haji Noor Deen and the exhibition very special,” said Professor Ali Asani, director of the Alwaleed Islamic Studies Program and chair of the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations.

Noor Deen strives to make his work accessible, giving demonstrations at schools and community centers across the world.

Harvard’s history of showcasing Islamic art dates at least as far back as 1945, when the Fogg Art Museum displayed “Treasures from the Islamic World.” The current exhibit promises to be more inviting, displaying the calligraphy much as it would be displayed in private homes and prayer spaces across the Muslim world.

To Krystina Friedlander, co-curator of the exhibit and program assistant at the Alwaleed Islamic Studies Program, the work and outreach of Noor Deen perfectly fit the program’s mission.

“Showcasing a Chinese artist helps open people’s eyes to the massive diversity in the Muslim world,” said Friedlander.

“Arabic Islamic Calligraphy in the Chinese Tradition: Works by Master Haji Noor Deen” will be on exhibit in the Japan Friends of Harvard Concourse, CGIS South, 1730 Cambridge St., Cambridge, Mass., through Aug. 20. The building is open 7 a.m.-7 p.m, Monday-Friday.

A closing reception will be held on Aug. 21 at 4:30 p.m.