Dancers perform “Aqua Borealis,” a work “inspired by deep-sea exploration and marine organisms that use light and movement to communicate in the oceans” at an event titled “Living Light: The Art and Science of Bioluminescence.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Deep glow

Bioluminescence is star of Science Center show

The dance began with darkness, and a voice: “The ocean is alive.” Green lights in the shape of human bodies flicked on and off from both sides of the auditorium. Living lights. “Imagine a world where light is the main form of communication,” the voice of oceanographer Sylvia Earle continued, as the dancers “swam” down stairs onto the stage. Their limbs flashed in time to music; slowly they breathed in and out, like swimmers in the sea.

The troupe was from New York-based Kristin McArdle Dance, at Harvard’s Science Center Tuesday to perform “Aqua Borealis,” a dance “inspired by deep-sea exploration and marine organisms that use light and movement to communicate in the oceans.” The dance was the climax of “Living Light: The Art and Science of Bioluminescence.”

“Too often we try to inspire people’s feelings by logic,” said Kathleen Frith, managing director of Harvard Medical School’s Center for Health and the Global Environment. “But people are not rational at all. We’re motivated by our emotions, our hearts, and our peers.” The purpose of the event, Frith said, was not to argue by reason, but to inspire respect for the oceans and the threats they face, through a mix of performance and science.

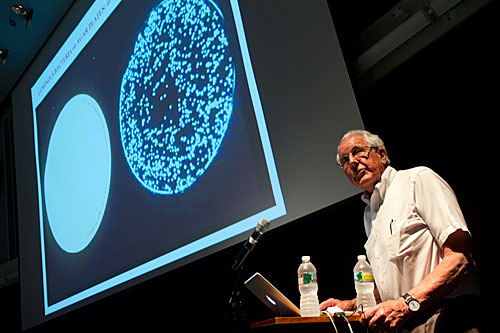

Science opened the night: images of glowing creatures from the deep, presented by Woody Hastings, professor emeritus of natural sciences in Harvard’s Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology. The creepy anglerfish dangles a bacteria-filled orb from its nose, which has a glow that attracts prey. Some species use that glow as defense, others to communicate — such as firefly squid off the coast of Japan, which flash to attract a mate.

Hastings recounted, too, the first time he saw “flashlight fish” — native to Indonesia, with huge eyes that glow blue — in the Red Sea, in 1968. These fish are so common off the Horn of Africa that they light up an area the size of Connecticut; the light can be seen by satellite.

The evening’s sponsors included the Harvard Museum of Natural History, Harvard Medical School’s Center for Health and the Global Environment, the Harvard Summer School, the Friends of the Farlow Library and Herbarium, W2O, and the Pleoades Network.

The night closed with a talk by Sylvia Earle: oceanographer, deep-sea explorer, author, and researcher, introduced by Frith as “Her Deepness.” Earle’s was the disembodied voice that began the dance, and it was her work as a National Geographic scholar and “explorer in residence” that first inspired McArdle to create “Aqua Borealis.” Earle, who showed a clip of one of her National Geographic documentaries, is a passionate conservationist and educator who believes, “You can’t care if you don’t know.”

“We all come from a different planet,” Earle said: The Earth is always changing. Today, she said, we are living at a “sweet spot in time,” a moment when we have more access to knowledge than Einstein did, and more power to affect the planet. A critical time not only for what we know, but for what we risk: “We are able to alter the nature of nature,” Earle warned, “by what we put into it.”

Education, Earle, said, is key to protecting the environment. After Earle met GoogleEarth creator John Hanke at a TED conference, she challenged him: “You’ve done a great job on the land. You should call it GoogleDirt.” The Google team countered by designing an “ocean” app for GoogleEarth, including clickable places such as the Sargasso Sea, where users can “dive in” to watch deep-sea videos like Earle’s.

Such knowledge gives people power, Earle said, and responsibility to protect the environment. “You can’t care if you don’t know,” she said. “But now we know.”