“We’re at such an early stage of microbiome work, we really don’t know what we’ll find,” said Arnold Arboretum Director William (Ned) Friedman. “I won’t be surprised if we find some new species, maybe some whole new groups.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

New branch of science

Ginkgo project key in effort toward first-ever tree microbiome

Botanists at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum know a lot about the 35-foot ginkgo tree near the sprawling park’s Walter Street gate.

They know it was rooted and planted by Peter del Tredici, who in 1989, as a Boston University doctoral student, took a four-inch cutting directly from one of the few remaining wild ginkgos in eastern China. They know it is one of 55 ginkgos growing in the Arboretum today. They also know it has the potential to live 1,000 years.

But even del Tredici, now a senior research scientist at the Arboretum, doesn’t know everything about the tree. That’s why del Tredici and Arboretum Director William (Ned) Friedman are collaborating with counterparts at the University of Colorado to learn more. Scientists in late June spent three days high off the ground, hoisted by the Arboretum’s bucket truck. Head arborist John Del Rosso and Colorado research associate Jon Leff collected 100 samples of the tree’s microbial life, the location of each swab painstakingly recorded with 10 different variables by Colorado graduate student Samantha Weintraub.

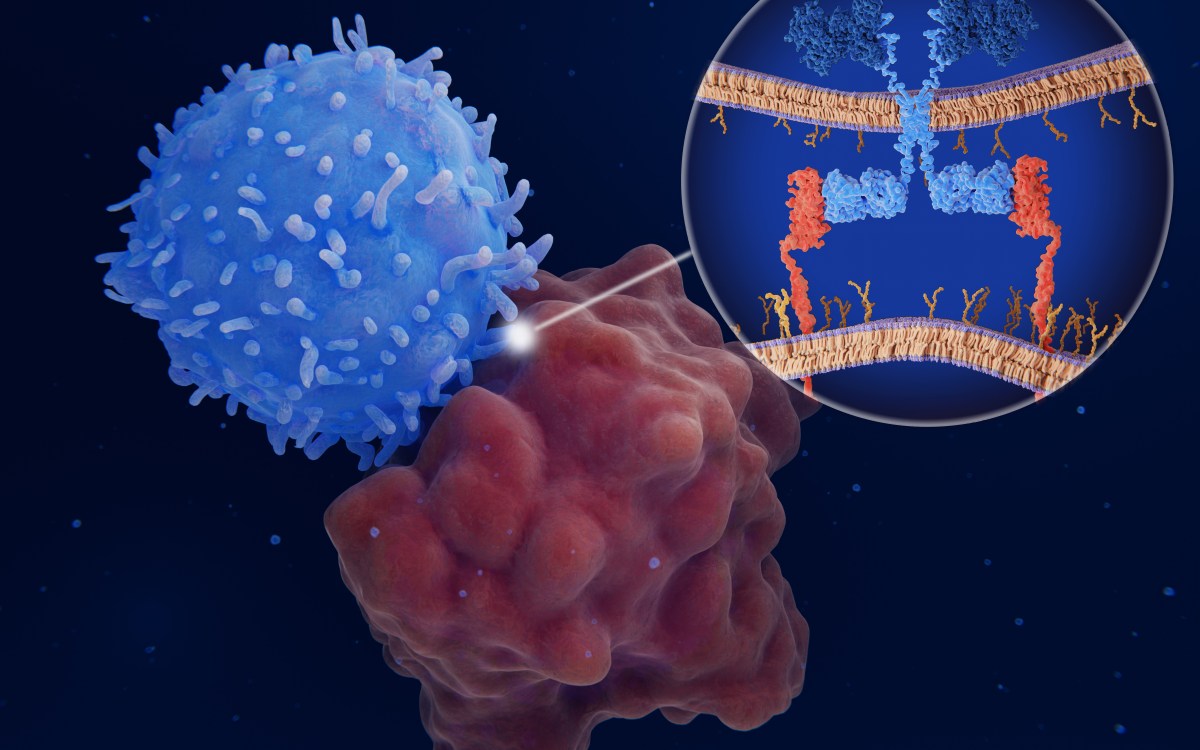

Friedman said the project is part of the first-ever effort to define the entire community of microbes — the “microbiome” — of a tree. Microbiome research made headlines this spring when a consortium of scientists published the first human microbiome, detailing the microbial community of healthy humans. That research emphasized that the trillions of microbes from some 1,000 species aren’t just along for the ride, they play important roles in digestion, immunity, and other bodily functions.

The microbiomes of plants are largely unknown, Friedman said, and the project will help scientists understand what kinds of microbes are living on the tree and whether the microbial communities vary according to location (trunk versus leaves, for example), amount of sunlight (north versus south side), or other factors. Comparisons with wild ginkgos in China and with other tree species should show whether geographic location — New England versus China — or species identification — ginkgos versus pines, for example — plays a role in determining microbial community.

The Arboretum, which holds an extensive collection of East Asian trees, is an ideal location for samples to be collected, Friedman said. Much of the analysis will be done in the Boulder lab of Noah Fierer, an assistant professor of biology with whom Friedman worked before leaving the University of Colorado for Harvard in January 2011.

“We’re at such an early stage of microbiome work, we really don’t know what we’ll find,” Friedman said. “I won’t be surprised if we find some new species, maybe some whole new groups.”