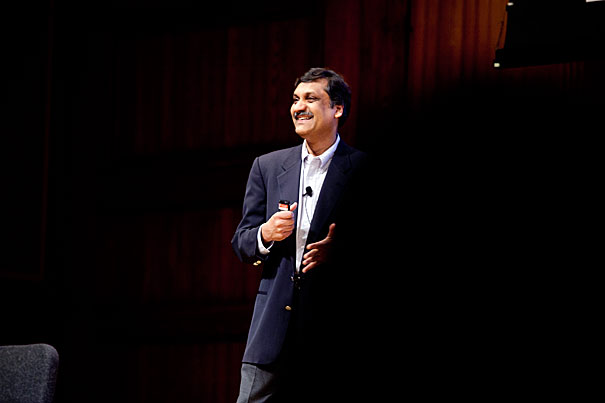

Anant Agarwal, edX’s first president, gave the keynote address at Harvard’s second annual IT Summit, a daylong conference that also included a discussion of the University’s strategic information technology plan by the CIO Council and 30 afternoon panels and presentations. “The courses we offer on edX are going to be Harvard hard, MIT hard,” he said. “They’re going to mean something.”

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Exploring edX 1.0

Head of program details new online education platform during IT Summit

When Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) announced their intention last month to provide free, online education, the world listened. The unveiling of edX, the universities’ joint open-source platform for web-based learning, garnered buzz around the globe.

The next question was obvious. What will edX — and the future of online higher ed — actually look like?

On Thursday, Anant Agarwal, edX’s first president, offered some early answers at Harvard’s second annual IT Summit. Agarwal’s keynote address at the daylong conference, which also included a discussion of the University’s strategic information technology plan by the CIO Council and 30 afternoon panels and presentations, introduced an ambitious project that will require just as much effort and innovation from Harvard’s IT professionals as it will from traditional educators.

“This really is an exciting time for all of us to be in IT and education, and it’s a particularly exciting time to be at Harvard in IT,” said Anne Margulies, Harvard’s chief information officer, who kicked off the summit at Sanders Theatre. “Together, MIT and Harvard are tackling the educational issue of our time: exploring how technology can really improve learning, and at the same time expand access to education around the world.”

Agarwal, professor of electrical engineering and computer science and director of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at MIT, led development of MIT’s earlier platform, MITx. As such, he was an obvious candidate for “the leader chosen to bring us all into this brave new world,” Margulies said.

Agarwal shared some lessons gleaned from MITx’s first pilot course, “MITx 6.002x: Circuits and Electronics.” As he would be the first to admit, the model for edX is hardly set in stone.

“Think of it as a not-for-profit online education startup,” he told his audience of several hundred.

When the course launched in February, it signed up 120,000 students — more than the number of undergrads MIT has graduated in its 150-year history. “The numbers are truly planet scale,” Agarwal said.

Of those enrolled, 20,000 took the first set of tests for the course, and 10,000 took the midterm exam. The low retention rate came in part because many casual students didn’t feel the need to take the tests, though many dropped out. Given the course’s suggested requirements — an AP-level physics course in electricity and magnetism, knowledge of basic calculus and linear algebra, and some background in differential equations — the five-digit enrollment numbers are still impressive, Agarwal said.

“The courses we offer on edX are going to be Harvard hard, MIT hard,” he said. “They’re going to mean something.”

Agarwal and his MITx team quickly learned to modify their best-laid plans according to student feedback. For lessons, students clearly preferred slightly messy, hand-drawn diagrams narrated by Agarwal — an intimate, digital facsimile of a professor’s chalkboard scrawl — to organized PowerPoint slides.

“Students like informal stuff; students like stuff that is personal,” he said.

To solve the problem of depersonalized instant grading and assessment, Agarwal and his colleagues discovered that “gamification is key.”

When a student answers a question correctly on the site, a green checkmark appears next to the answer. Students, they found, will keep trying to answer a practice question correctly until they succeed in finding the answer, seeking the instant gratification of the green checkmark. Compared with students in a traditional, offline trial version of the course, MITx students were actually spending more time on assignments, thanks in part to instant results for their efforts, Agarwal said.

“Immediate feedback is huge,” he said. “I think the green checkmark is going to become the symbol of online learning.”

Students engaged with the course in other ways. Though Agarwal has a co-instructor and four teaching assistants, managing tens of thousands of students’ questions would be impossible with the limited staff. The course’s discussion section has thus far managed the problem by allowing students to post their questions, which other students can then up-vote to the top of the queue. Students get “karma points” for asking popular questions or for providing answers.

“If you get enough karma points, you get to be an instructor,” Agarwal said, though he joked that he’s received “some complaints that they’re wielding authority heavy-handedly.”

There have been some heartening successes beyond student engagement, as well. At first, Agarwal said, he struggled to persuade science and health publisher Elsevier to post parts of “Foundations of Analog and Digital Electronic Circuits” online for free for the course’s students. The company balked, reasoning that giving away course materials would devalue the textbook.

Elsevier ended up selling “every copy of the book in the world,” Agarwal said, due to high demand from the thousands of students enrolled in “6.002x.” Now the publisher is eager to partner with edX for future courses. It’s an instructive reminder, he said, that in the world of online, mass-scale education, the old rules — in publishing, in higher education, in teaching and learning — no longer apply.

“There’s a lot we still need to learn,” Agarwal said. But “all the things they said can never be done, they can be done.”