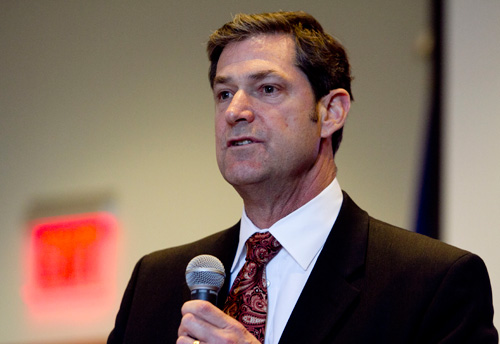

Harvard Professor Steven Pinker spoke to a full house at the Boston Public Library’s Honan-Allston Branch. Pinker, who discussed his new book, “The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined,” was part of the John Harvard Book Celebration lecture series, which continues April 1 at the Cambridge Public Library with Anne Fadiman.

Photos by Amanda Swinhart/Harvard Staff Photographer

Pinker explains ‘The Long Peace’

Trade, literacy, governments all have helped to reduce world violence

Violence may seem to be all around us. Soldiers are fighting in Afghanistan. Drug-related shootings and senseless murders splash across the nightly news, and even the schools are no haven, with episodes of hazing and bullying prompting a national discussion on how to keep children safe — from each other.

Violence may seem to be wherever we look, but the perception that we live in violent times is wrong, Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker said Tuesday evening during a talk at the Boston Public Library’s Honan-Allston Branch.

Pinker, the Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology and Harvard College Professor, said we’re actually in a period referred to by scholars as “The Long Peace,” which began at the end of World War II, and which is marked by the absence of war among the world’s great powers.

But that’s just part of the picture, Pinker said. Interpersonal violence is also at a historic low, he said, likely brought about by the spread of civilization, of police and justice systems, of literacy and global trade, and by concepts of civil and human rights.

“Violence has been in decline for long stretches of time, and today may be the most peaceful era in our species’ history,” Pinker said.

Pinker spoke as part of the John Harvard Book Celebration, a lecture series that brings prominent Harvard speakers and other programs to each public library in Cambridge and Boston in connection with the University’s 375th anniversary festivities. The talks are coupled with the gift of 400 books to each city’s library systems to commemorate those donated by Harvard’s namesake, John Harvard, to the College’s nascent library in 1638.

Kevin Casey, Harvard’s associate vice president for public affairs and communications, introduced Pinker, saying that his talk and the John Harvard Book Celebration are extending the 375th celebration into the communities of which Harvard is a part.

“Tonight we’re going to talk about the ideas and the things that happen inside the walls of a university and a place like Harvard,” Casey said. “It’s an effort to … bring what happens at Harvard into our [neighborhoods]. We think that by touching every corner of Boston and Cambridge, it shows that Harvard really is part of these communities.”

Several members of the audience explained afterward how they enjoyed the talk. Sarah Griffith of Cambridge said Pinker changed some of her assumptions about violence generally and altered her sense of World War II by viewing it over the long span of history.

“He did change a lot of the ways I thought about violence and changed some of my assumptions about what has gone on,” Griffith said.

Pinker’s talk was based on his latest book, “The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined,” published last year.

Records of past wars and new research into the lifestyles of ancient man provided the backdrop for Pinker’s assertions. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle before the rise of civilization was a violent one, Pinker said. Studies of ancient human remains have shown that some kind of violent trauma — skulls bashed in, arrows lodged in bones — accompanied roughly 15 percent of burials. By contrast, deaths related directly and indirectly to war, genocide, and famine during the 20th century, often considered the most violent because of its two world wars, amounted to just 3 percent, Pinker said.

Additional insight is gained by studying modern hunter-gatherer societies. Those studies have shown that there are about 524 violent deaths per 100,000 in those societies, compared with an overall rate of violent death in the 20th century of about 60 per 100,000.

Pinker attributed the long decline in violence to the rise of civilization, with centralized governments and disinterested third parties like police and court justices to resolve disputes. In England, where records have been kept for centuries, the modern Englishman has just one-fiftieth the chance of being murdered compared with his medieval ancestor 800 years ago.

Commerce may also be a major factor in the decline of violence, Pinker said. Trade means that transactions where both parties come out ahead become more attractive than theft and plunder, where only one side wins, at potentially great cost to both sides.

Major milestones on the march from a violent past include the abolition of judicial torture, which used to include horrific practices like impalement, sawing in half, and breaking bones on a wheel. Other factors include the abolition of slavery and the decline of the death penalty, and the abolition of dueling, lynching, and blood sports.

The violence during World Wars I and II was indeed horrific, but when compared with the planet’s population at the time, World War II ranks just ninth in major conflicts, while World War I isn’t in the top 10. Wars between the world’s great powers used to be regular, if not continual, and lasted for decades, as in the 30 Years’ War and the 100 Years’ War.

Since World War II, the nature of war on the planet has changed, Pinker said. Nations that might be considered great powers, which once warred regularly, have had an extended period of peace, colonial wars have tapered off, and the most common form of warfare now is civil war, which is less deadly than major conflicts between large nations.

Even interpersonal violence is declining, with the incidence of rape down 80 percent since the early 1970s, with declines in the deaths of wives and husbands at the hands of their spouses, with the acceptance of corporal punishment in schools falling, and with rates of physical and sexual abuse of children also declining.

Pinker said he doesn’t believe that humans have become inherently less violent or that such tendencies have been bred out of them. Rather, he said, people have always been complex creatures. The civilizing effects of institutions, combined with the spread of literacy, education, and public discourse, have all favored our nonviolent inclinations, he said.

In the end, Pinker said, it’s important to recognize these peaceful trends so they can be better understood.

“I believe that calls for a rehabilitation of the ideals of modernity and progress, and it’s a cause for gratitude for the institutions of civilization and enlightenment that made it possible,” Pinker said.

John Harvard Book Celebration continues with Anne Fadiman discussing “Using Bacon for Bookmarks: How Readers Treat their Books.” Fadiman is an author, essayist, editor, and teacher, as well as a member of Harvard’s Board of Overseers. The talk will be from 4 to 5 p.m. April 1 at the Cambridge Public Library’s main branch, 449 Broadway.