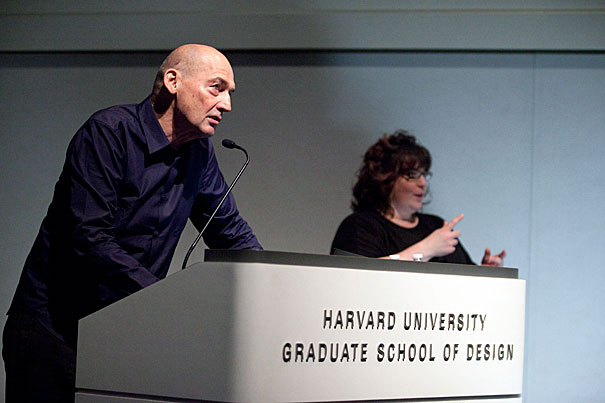

Colorful architect and urban theorist Rem Koolhaas shared his thoughts before an overflow crowd at Piper Auditorium with a presentation titled “Current Preoccupations.” Koolhaas is a professor in the practice of architecture and urban design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Critical preoccupations

Koolhaas presentation intertwines architecture, urban theory

Architect and urban theorist Rem Koolhaas is doing a lot of critical thinking these days, about architects in popular culture, the West’s irrational moroseness, the transformation of Swiss landscape, and global warming.

Koolhaas, who recently told The Guardian newspaper he’s his own “criticism machine” when it comes to analyzing his own work, dove head-on last night into a host of thorny issues – including criticism.

“Everything we do and say is critical,” Koolhaas said. “But architecture itself can’t be critical of anything.”

Koolhaas, a professor in practice of architecture and urban design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), shared his thoughts on those and other subjects before an overflow crowd at Piper Auditorium with a presentation titled “Current Preoccupations.”

The Pritzker Prize-winning architect’s wide-ranging program riffed off his exhibition by the same name at London’s Barbican art center, and featured a slide-show sampling of insights into the intertwined spheres of architecture, environment, history, and politics.

He also took questions from panelists Sanford Kwinter, a GSD professor of theory and criticism, and K. Michael Hays, Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory at the GSD.

Tall, lean, and bespectacled, Koolhaas hunched over a microphone and, speaking in a rapid clip with a slight Dutch accent, began picking the world apart.

Koolhaas pointed to the sinking status of architects in the public eye, noting they appeared on the cover of Time magazine regularly from 1920 through the 1940s, but never again after 1979 when Philip Johnson last graced the cover. From then, Time and other publications were bullish for Wall Street moneymen.

His next target was Francis Fukuyama, who morosely declared “the end of history” in 1992. Koolhaas said “moroseness” is a Western problem, while exuberance characterizes other parts of the world.

A champion of unique urban design — such as his innovative glass-and-steel Seattle Public Library building, Koolhaas also critiqued star architects who design anonymous buildings without character.

Over the past 10 years, Koolhaas watched a Swiss village where he lived transform. The original inhabitants moved away, and foreign laborers were imported. Scenic meadows were landscaped, and modern architecture replaced traditional.

“I’m not saying all this is bad, but it’s ironic that such drastic transformations are barely or rarely taught in our schools,” Koolhaas said. “I want to find ways to discuss and think about it.”

Global warming also is on his radar. Recently returned from Vladivostok, Koolhaas ventured that Russia could be the big winner from global warming, with its cold climes transformed into the breadbasket of the world – if only its corrupt politics allowed it.

“The irony is there are no Russians to exploit this new condition,” Koolhaas said.

Koolhaas, co-founder of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, also discussed his new book on the Japanese Metabolists: “Project Japan.”

The Metabolists were members of an architectural design movement arising from the ashes of post-World War II Japan.

However, Koolhaas and co-author Hans Ulrich Obrist traced the movement’s origins to Japan’s invasion of Manchuria, where imperial architects’ imagination was fired by the tabla rasa of the conquered Chinese province’s wide-open spaces. No longer confined by Japan’s cramped island, these architects began designing modernist buildings.

Ironically, a Japan devastated by U.S. bombing served as a similar blank slate for Metabolists like Kiyonori Kikutake and Kenzo Tange, whose technocratic and avant-garde designs were on the cutting edge of architecture from the late 1950s into the early 1970s.

The Metabolists’ legacy includes innovative megastructures, floating cities, and capsule towers.

Koolhaas said that although much of his work has focused on Europe and Asia, he hopes to tackle an African film project he began years ago but shelved because it was “politically incorrect.”

“I was intimidated to tell my story,” Koolhaas said. “Only now am I confident enough to say what I have to say.”

Asked by a student if his feeling that Western civilization has gone morose meant he was folding up his drafting table, Koolhaas would have none of it.

“I don’t feel I’m approaching the end of my career,” Koolhaas said. “Otherwise, I wouldn’t be playing these kind of games.”