When faced with a tough choice, we already have the cognitive tools we need to make the right decision, Daniel Gilbert, a professor of psychology at Harvard, told his Law School audience.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Right choice, but not the intuitive one

Psychologist explores common barriers to good decision-making

To take a gratifying, low-paying job or a well-paid corporate position, to get married or play the field, to move across the country or stay put: The fact that most people face such choices at some point in their lives doesn’t make them any easier. No one knows the dilemma better than law students, who are poised to enter a competitive job market after staking years of study on their chosen field.

When faced with a tough choice, we already have the cognitive tools we need to make the right decision, Daniel Gilbert, professor of psychology at Harvard and host of the PBS series “This Emotional Life,” told a Harvard Law School (HLS) audience on Feb. 16. The hard part is overcoming the tricks our minds play on us that render rational decision-making nearly impossible.

Gilbert’s talk, titled “How To Do Precisely the Right Thing at All Possible Times,” was part of Living Well in the Law, a new program sponsored by the HLS Dean of Students Office that aims to help law students consider their personal and professional development beyond the fast track of summer associate positions and big-law job offers.

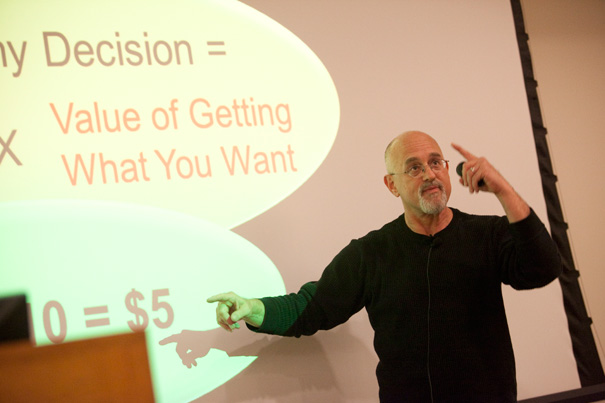

There is a relatively simple equation for figuring out the best course of action in any situation, Gilbert explained: What are the odds of a particular action getting you what you want, and how much do you value getting what you want? If you really want something, and you identify an action that will make it likely, then taking that action is a good move.

Unfortunately, Gilbert said, “these are also the two ways human beings screw up.”

First, he said, humans have a hard time estimating how likely we are to get what we want. “We know how to calculate odds [mathematically], but it’s not how we actually calculate odds,” he said.

We buy lottery tickets, because we “never see interviews with lottery losers.” If every one of the 170 million losing ticket holders were interviewed on television for 10 seconds apiece, we’d be having the image of losing drilled into our brains for 65 straight years, he said.

“When something’s easy to imagine, you think it’s more likely to happen,” he said.

For example, if asked to guess the number of annual deaths in the United States by firework accidents and storms versus asthma and drowning, most people will vastly overestimate the former and underestimate the latter. That’s because we don’t see headlines when someone dies of an asthma attack or drowns, Gilbert said. “It’s less available in your memory, but it is in fact more frequent.”

Then there’s the fact that we’re prone to irrational levels of optimism, a pattern that has been documented across all areas of life. Sports fans in every city believe their team has better-than-average odds of winning; the vast majority of people believe they’ll live to be 100.

A study of Harvard seniors, Gilbert gleefully reported, showed they on average believed they’d finish their theses within 28 to 48 days, but most likely within 33 — “a number virtually indistinguishable from their best-case scenario.” In reality, they complete their theses within 56 days on average.

Still, he said, calculating our odds of success is actually the easy part. “What’s really hard in life is knowing how much you’re going to value the thing you’re striving so hard to get,” he said.

When we consider buying a $2 cup of coffee at Starbucks, for example, we don’t compare the satisfaction of a morning caffeine jolt against the millions of other things we could purchase for $2. Rather, we compare the value of that cup of coffee against our own past experiences. If the same coffee only cost $1.50 yesterday, we might balk at paying $2 for it today.

“One of the problems with this bias, this tendency to pay attention to change, is that it’s hard to know if things really did change,” he said. “Whether things changed is often in the eye of the beholder.

“It turns out that every form of judgment works by comparison,” he said. “People shop by comparison.” Unfortunately, our comparisons are easily manipulated, and comparing one option with all other possible options is an impossible task.

Real estate companies, for example, show potential buyers “set-up properties,” rundown fixer-uppers that they actually own, to lower their clients’ expectations for houses that are actually for sale.

In his own lab, Gilbert’s research team had two groups of college students predict how much they would enjoy eating a bag of potato chips. The group that sat in a room with chocolates on display predicted they’d enjoy the chips less, while the second group — stuck in a room with the chips and a variety of canned meats — predicted much higher enjoyment of the salty snack.

But when the students rated their enjoyment of the chips while they were eating them, those differences disappeared. While their previous visual judgment was tainted by comparison, their judgment of the actual taste was not.

“The comparisons you make when you’re shopping are not the ones you’ll make after you’ve bought,” Gilbert said.

The human mind evolved to deal with different dilemmas than the ones we face today, Gilbert explained. Our ancestors weighed short-term consequences to ensure their survival, evolving a snap-judgment process that often serves us poorly when making long-term decisions such as buying a home, investing in the stock market, or making a cross-country move.

The brain “thinks like the old machine it is,” Gilbert said. “We are in some sense on a very ancient vessel, and we are sailing a very ancient sea.”

Still, he told his audience, we have the ability to overcome these evolutionary roadblocks to self-aware, smart decision-making, as long as we acknowledge our biases.

“We’ve been given that gift,” Gilbert said. “The question is, will we use it?”