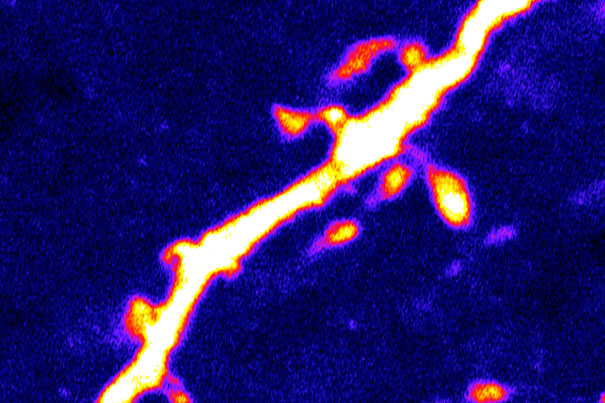

The scientists found that a 24-hour period of fasting — which causes intense hunger in the control mice — was associated with a 67 percent increase in the number of dendritic spines (pictured) on the AgRP neurons.

Images courtesy of Dong Kong/BIDMC

Exploring roots of hunger, eating behaviors

Study demonstrates that plasticity in the brain’s wiring controls feeding behavior

Synaptic plasticity — the ability of the synaptic connections between the brain’s neurons to change and modify over time — has been shown to be a key to memory formation and the acquisition of new learning behaviors. Now research led by a scientific team at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) reveals that the neural circuits controlling hunger and eating behaviors are also controlled by plasticity.

The roots of hunger, eating, and weight are based in the brain’s complex and rapid-fire neurocircuitry. Over the years, nerve cells containing agouti-related peptide (AgRP) protein and pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) protein have emerged as critical players in feeding behaviors. Located in the hypothalamus, the brain area that controls automatic body functions, AgRP neurons have been shown to drive eating and weight gain while POMC neurons inhibit feeding behaviors, causing satiety and weight loss.

Described in the Feb. 9 issue of the journal Neuron, the findings show that during fasting, the AgRP neurons that drive feeding behaviors actually undergo anatomical changes that cause them to become more active, which results in their “learning” to be more responsive to hunger-promoting neural stimuli.

“The role of plasticity has generally not been evaluated in neuronal circuits that control feeding behavior, and with this new discovery we can start to unravel the basic mechanisms underpinning hunger and gain a greater understanding of the factors that influence weight gain and obesity,” explains senior author Bradford Lowell, an investigator in BIDMC’s Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School (HMS).

Adds BIDMC Chairman of Neurology Clifford Saper, “For most animals, finding enough food to survive is their biggest daily challenge, and so the brain’s increase in feeding drive may be adaptive. But, for humans who are overweight, reducing this drive to the AgRP neurons may prove to be a path to future weight loss therapies.”

Previous work by the Lowell lab and others had demonstrated that when AgRP neurons in mice are artificially switched on, the animals eat voraciously, consuming four times more than control animals. “The ‘switched-on’ animals search in an unrelenting fashion for food, and when given a task to obtain pellets, will work five times harder to get them,” Lowell explains. “Given the important role played by AgRP neurons, we had a great interest in understanding the factors that regulate their activity.” While much focus had centered on hormones, including leptin, insulin, and ghrelin, the Lowell team hypothesized that other nerve cells might be the mechanisms that were regulating neuronal activity.

Neurons communicate with one another via neurotransmitters, chemical messengers that traverse synapses, the specialized junctions between upstream and downstream neurons. Glutamate is one such excitatory neurotransmitter.

“Studies in other regions of the brain [for example, those controlling learning and reward and addiction behaviors] have demonstrated that glutamate synapses are highly plastic, changing in their strength and sometimes even in their number,” explains Lowell. Shown to exert powerful control over behavior, synaptic plasticity is brought about when glutamate binds to NMDA receptors on downstream neurons.

“When glutamate gets released by upstream neurons and binds to NMDA receptors, calcium enters the downstream neuron. This, in turn, engages signal transduction pathways that cause synaptic plasticity. In other parts of the brain, such as the hippocampus, NMDA receptors drive plasticity which serves to encode memories,” Lowell adds.

Led by co-first authors — Tiemin Liu, Dong Kong, Bhavik P. Shah, and Chian Ping Ye — the investigators created and studied mice genetically engineered to lack glutamate-binding NMDA receptors on the AgRP neurons. For the sake of comparison, they also created mice genetically engineered to lack NMDA receptors on POMC neurons.

They found that while mice lacking NMDA receptors on POMC neurons showed no change in feeding behavior, the situation was dramatically different in the mice lacking NMDA receptors on AgRP neurons. “These mice ate a lot less and were much skinnier than a group of control mice,” explains Lowell. Furthermore, the scientists found that a 24-hour period of fasting — which causes intense hunger in the control mice — was associated with a 67 percent increase in the number of dendritic spines on the AgRP neurons.

“Dendritic spines are tiny structures attached to the neuron’s dendrites, the treelike branches that receive incoming signals from upstream neurons,” explains Lowell. “These structures are the physical site, the subcellular communication hub, where synaptic input from upstream glutamate-releasing neurons is received, typically one synaptic input per spine.”

“I’ve been studying spines for a long time and I’ve never before seen a manipulation that triggered such rapid and robust changes in spine number,” says co-author Bernardo Sabatini, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator in the Department of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School (HMS). “Clearly, feeding is plugging in to the most basic mechanisms that control synapse and spine number in these cells. This may be a great system to understand not only feeding behavior, but also to understand the cell biology behind dynamic synapse formation and retraction.”

When the control mice were re-fed — and their hunger alleviated — the number of spines dropped back to normal. (In contrast, fasting had no effect on spine number in the mutant mice lacking NMDA receptors on AgRP neurons.) These dramatic changes in spine number and their tight association with states of hunger and satiety in control mice — and the absence of changes in spine number in mice lacking NMDA receptors on the downstream AgRP neurons — strongly suggests that structural plasticity of excitatory glutamate synapses on AgRP neurons is an important regulator of feeding behavior, says Lowell.

“Obesity is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain types of cancer,” he adds. “By understanding the neurobiological mechanisms underlying feeding behaviors, we can work on treatments for a problem that has now become a global epidemic. These findings move us closer to a mechanistic understanding of how various factors controlling hunger might work.”

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the American Diabetes Association, as well as support from the Shapiro Predoctoral Fellowship and the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation postdoctoral fellowship programs.

In addition to Lowell, Sabatini, and the paper’s first authors, other co-authors include BIDMC investigators Shuichi Koda and Zongfang Yang and HMS investigators Arpiar Saunders and Jun B. Ding.