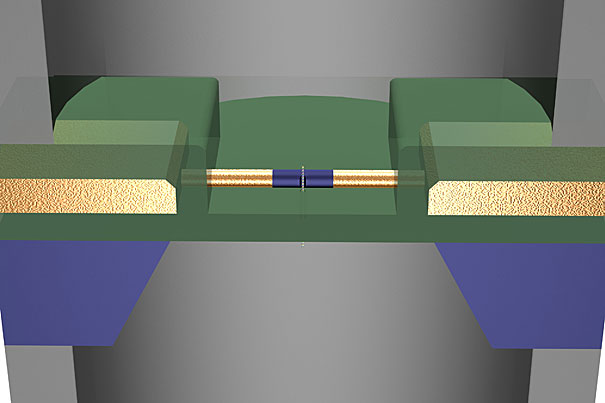

In a recent Nature Nanotechnology paper, researchers from Harvard demonstrated that nanowire transistors can locally read and amplify the DNA translocation signal from a nearby nanopore.

Image courtesy of Ping Xie, Qihua Xiong, Ying Fang, Quan Qing, and Charles M. Lieber

Reading life’s building blocks

Harvard researchers develop tools to speed DNA sequencing

Scientists are one step closer to a revolution in DNA sequencing, following the development in a Harvard lab of a tiny device designed to read the minute electrical changes produced when DNA strands are passed through tiny holes — called nanopores — in an electrically charged membrane.

As described in Nature Nanotechnology on Dec. 11, a research team led by Charles Lieber, the Mark Hyman Jr. Professor of Chemistry, have succeeded for the first time in creating an integrated nanopore detector, a development that opens the door to the creation of devices that could use arrays of millions of the microscopic holes to sequence DNA quickly and cheaply.

First described more than 15 years ago, nanopore sequencing measures subtle electrical current changes produced as the four base molecules that make up DNA pass through the pore. By reading those changes, researchers can effectively sequence DNA.

But reading those subtle changes in current is far from easy. A series of challenges — from how to record the tiny changes in current to how to scale up the sequencing process — meant the process has never been possible on a large scale. Lieber and his team, however, believe they have found a unified solution to most of those problems.

“Until we developed our detector, there was no way to locally measure the changes in current,” Lieber said. “Our method is ideal because it is extremely localized. We can use all the existing work that has been done on nanopores, but with a local detector we’re one step closer to completely revolutionizing sequencing.”

The detector developed by Lieber and his team grew out of earlier work on nanowires. Using the ultra-thin wires as a nanoscale transistor, they are able to measure the changes in current more locally and accurately than ever before.

“The nanowire transistor measures the electrical potential change at the pore and effectively amplifies the signal,” Lieber said. “In addition to a larger signal, that allows us to read things much more quickly. That’s important because DNA is so large [that] the throughput for any sequencing method needs to be high. In principle, this detector can work at gigahertz frequencies.”

The highly localized measurement also opens the door to parallel sequencing, which uses arrays of millions of pores to speed the sequencing process dramatically.

In addition to the potential for greatly improving the speed of sequencing, the new detector holds the promise of dramatically reducing the cost of DNA sequencing, said Ping Xie, an associate of the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology and co-author of the paper describing the research.

Current sequencing methods often start with a process called the polymerase chain reaction, or DNA amplification, which copies a small amount of DNA thousands of millions of times, making it easier to sequence. Though critically important to biology, the process is expensive, requiring chemical supplies and expensive laboratory equipment.

In the future, Xie said, it will be possible to build the nanopore sequencing technology onto a silicon chip, allowing doctors, researchers, or even the average person to use DNA sequencing as a diagnostic tool.

The breakthrough by Lieber’s team could soon make the transition from lab to commercial product. The Harvard Office of Technology Development is working on a strategy to commercialize the technology appropriately, including licensing it to a company that plans to incorporate it into their DNA sequencing platform.

“Right now, we are limited in our ability to perform DNA sequencing,” Xie said. “Current sequencing technology is where computers were in the ’50s and ’60s. It requires a lot of equipment and is very expensive. But just 50 years later, computers are everywhere, even in greeting cards. Our detector opens the door to doing a blood draw and immediately knowing what a patient is infected with, and very quickly making treatment decisions.”