In 1924, Western Electric began conducting experiments to test ways of improving workers’ productivity. This photo shows the factory cabling department, ca. 1925. The experiments would eventually revolutionize the workplace.

Photos courtesy of the Baker Library Historical Collections/HBS

Rethinking work, beyond the paycheck

During Great Depression, human relations movement took shape through HBS

As Harvard celebrates its 375th anniversary, the Gazette is examining key moments and developments over the University’s broad and compelling history.

If it’s true that man cannot live by bread alone, perhaps an office worker’s credo would follow: A man — or a woman — cannot work on a paycheck alone.

Often, perks both tangible and intangible make a job worth waking up for. A sense of accomplishment, pride in an organization, and the rare week off for the holidays (as most Harvard employees can attest) go a long way toward making workers more productive.

It seems intuitive now. But 80 years ago, the idea that workers were purely rational beings motivated solely by money dominated in business schools and corner offices across America. If not for a famous study known as the Hawthorne Experiments — and the two men at Harvard Business School who led them — workers might still be seen as cogs in the machine.

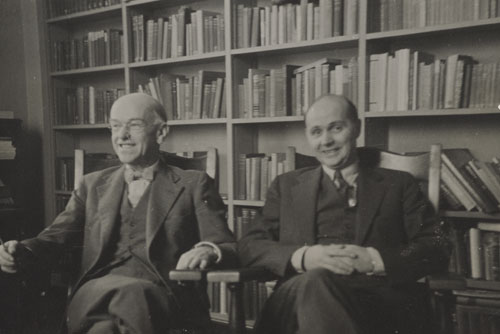

From 1928 to 1933, Elton Mayo, a professor of industrial management at HBS, and his protégé, Fritz Roethlisberger, undertook a series of groundbreaking experiments at a Chicago factory that reshaped business research, reframed management education, and rewrote the gospel of work. Their novel approach to treating workers as complicated individuals, and in turn viewing organizations as complex social systems, laid the groundwork for the human relations movement.

The Hawthorne Experiments represented “a huge paradigm shift” in the nascent field of organizational behavior, said Jay Lorsch, Louis E. Kirstein Professor of Human Relations at HBS, who studied under Roethlisberger. Amid the crushing realities of the Great Depression, the study used empirical research to build a compelling case that a happy worker makes for a hard worker, and in turn for a more successful organization.

It all began at Western Electric Hawthorne Works, a Chicago complex that served as the manufacturing arm of AT&T. The plant housed more than 40,000 workers who assembled and inspected countless telephones, cables, and other communications equipment.

In 1924, Western Electric began conducting experiments to test ways of improving workers’ productivity. Would brighter lights speed up production? Tests indicated not. Would rest periods, shorter hours, or a bonus for meeting quotas lead to higher output? Again, the company found no conclusive results.

Stumped, the Western Electric bosses turned to Mayo, who was already making a name for himself at HBS. A charismatic Australian, Mayo represented a new way of thinking about industry.

At the time, the theory of “scientific management” dominated business schools. Many of its proponents were industrial engineers or former military men, trained to think in terms of strict efficiency. An organization, these thinkers argued, could be laid out and studied as rationally as a machine blueprint or a battle plan.

Mayo, on the other hand, was well versed in Freud and Jung and sympathetic to the human sciences, from anthropology and psychology to medicine. In fact, Roethlisberger, then a graduate student in philosophy at Harvard, first sought out Mayo not to work with him but in the hopes of receiving some counseling, according to Lorsch. The two became collaborators on a study of worker fatigue.

When he arrived in Chicago in 1928, Mayo quickly realized that Western Electric’s lighting experiments were a dead end. Much richer data lay in the workers themselves. Soon, Mayo and Roethlisberger shifted the primary focus of the experiments to just six women who worked in the plant’s relay assembly test room.

Mayo and Roethlisberger “walked into the plant saying, ‘We don’t actually know anything, and therefore we need to record everything,’ ” said Michel Anteby, an associate professor of business administration and a Marvin Bower Fellow at HBS, who co-wrote an essay on Mayo and Roethlisberger’s work for a 2007 Baker Library exhibit about the Hawthorne Experiments. “You could call it systematic. You could also call it compulsive.”

Indeed, Mayo and Roethlisberger oversaw more than 21,000 interviews with their test subjects between 1928 and 1930. Like many Chicago workers at the time, most of the young women came from Eastern European immigrant families.

“She’s the breadwinner of the family, housekeeper for her father and brothers, has brown hair, is vivacious,” read one entry. (The Baker Library has the records from the Hawthorne Experiments in its collections.) “Has been known to go directly from late-Saturday-night dance to Sunday-morning Mass.”

From stacks of interview transcripts and reams of resulting data, Mayo and Roethlisberger concluded that the women were motivated by an array of factors, from a desire to support their families to a sense of camaraderie they felt with their co-workers. Employees found their personal relationships with one another “so satisfying that they often did all sorts of nonlogical things … in order to belong,” Roethlisberger wrote.

In 1933, amid economic turmoil and social unrest, Mayo published “The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization,” but his manifesto did not immediately catch on. Six years later, Roethlisberger and William Dickson, another researcher on the Hawthorne project, wrote a summary of the experiments, “Management and the Worker,” that had more commercial success.

Even in the early 1950s, Lorsch recalled from his own education, many business schools were still teaching students “that motivation was all about money, the classic ideas of command and control.” But in the 1950s and ’60s, other scholars took up Mayo and Roethlisberger’s cause and succeeded in popularizing their ideas.

“The thing that was powerful and common in all of it was that human beings needed to be motivated,” Lorsch said. “They weren’t just working for money.”

Thanks to Mayo and Roethlisberger’s high methodological standards (then unusual in business research), the experiments had a broader impact on the social sciences. The “Hawthorne effect” — a term coined in the 1950s — describes the phenomenon of test subjects changing their performance on a test in response to being observed, as some Hawthorne employees did when they knew they were part of the study. Researchers now use randomized clinical trials, control groups in experiments, and other safeguards that attempt to weed out bias in studies.

The Hawthorne Experiments in major ways laid the foundation for the modern workplace. Human relations departments, employee engagement surveys, and hundreds of popular books on business psychology echo Mayo and Roethlisberger’s call to focus on the human side of industry.

“All research on work-life balance goes back to some of their insights,” Anteby said. “You wouldn’t carve out the workplace as a 9-to-5 environment that’s disconnected from the rest of your life.”

Not least of all, the Hawthorne Experiments can inspire anyone hoping to study organizational behavior, Anteby said.

“Almost 80 years later, you can go to [the Baker Library] and get a typed transcript of someone talking about her hopes, her life, coming to America, and how she’s trying to support her family,” he said. “It crystallizes what work is about, and the meaning of work.”